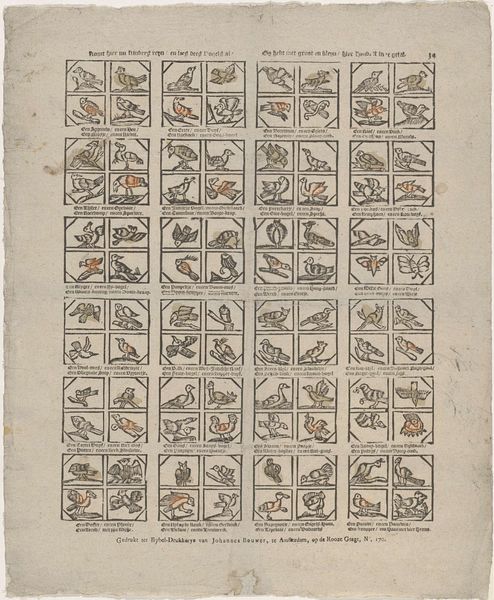

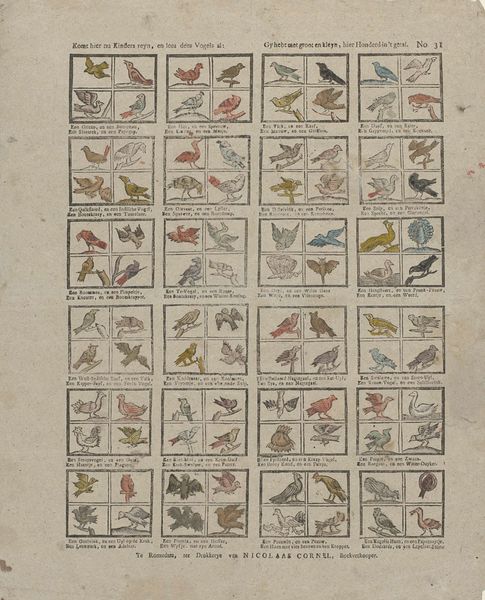

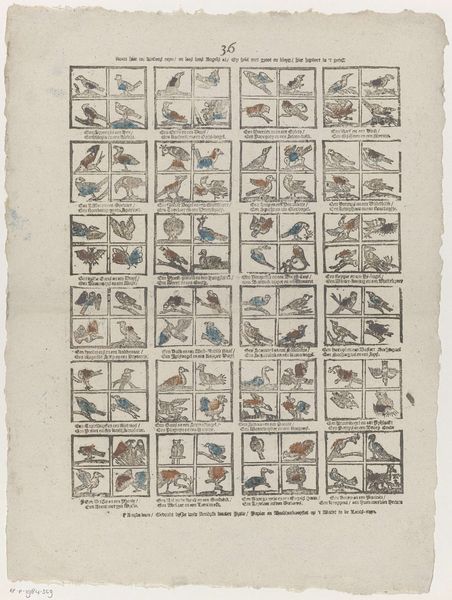

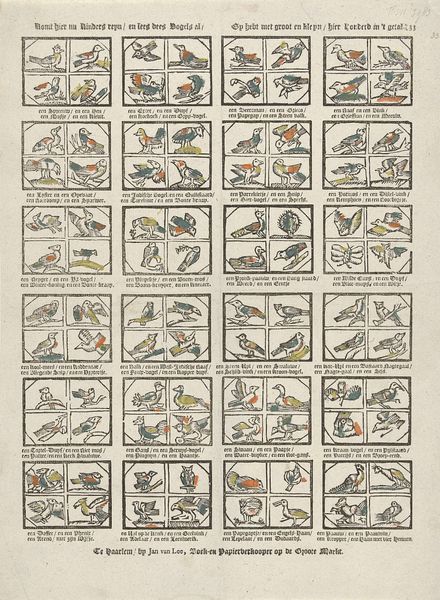

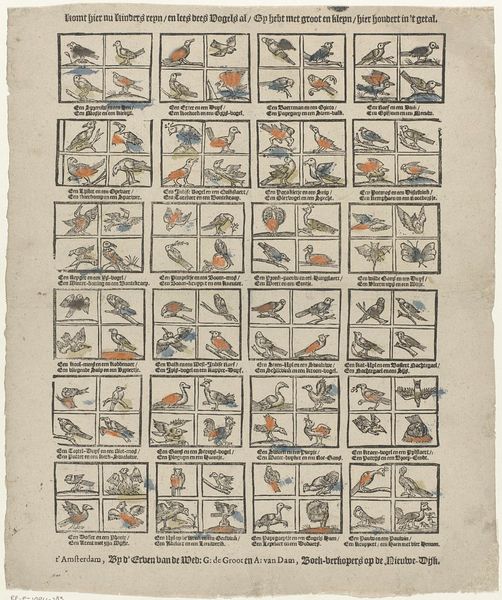

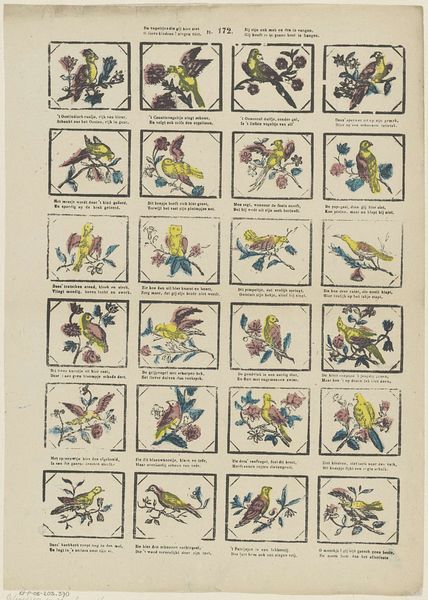

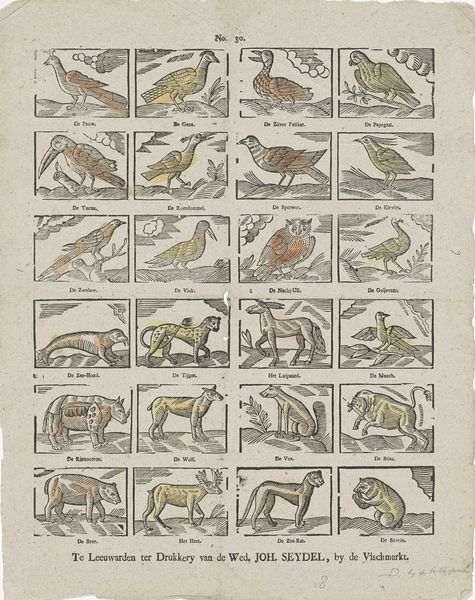

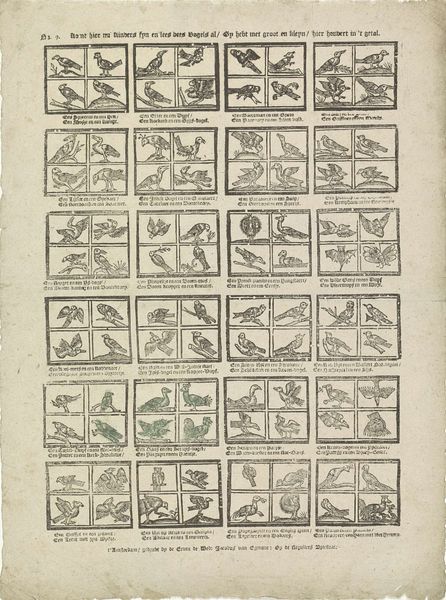

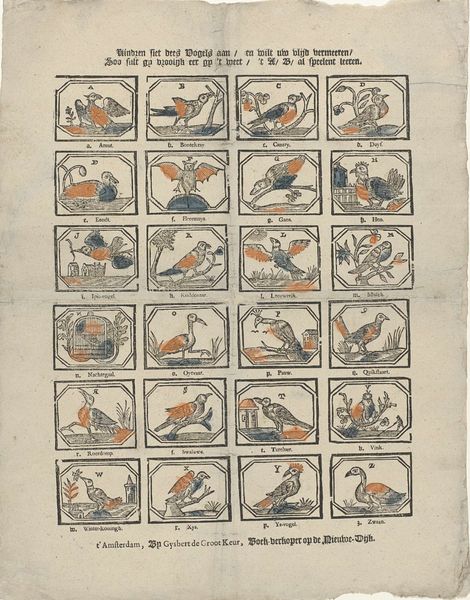

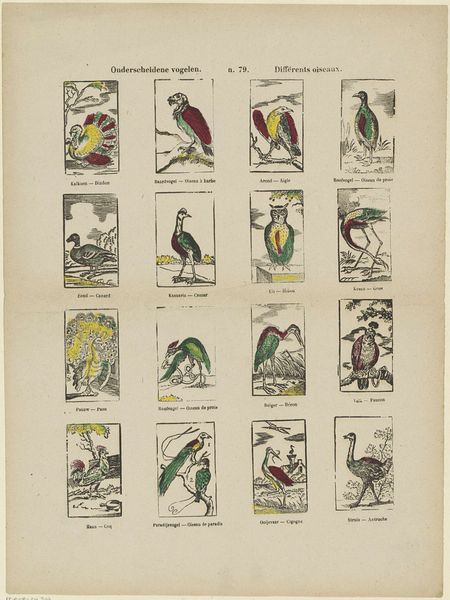

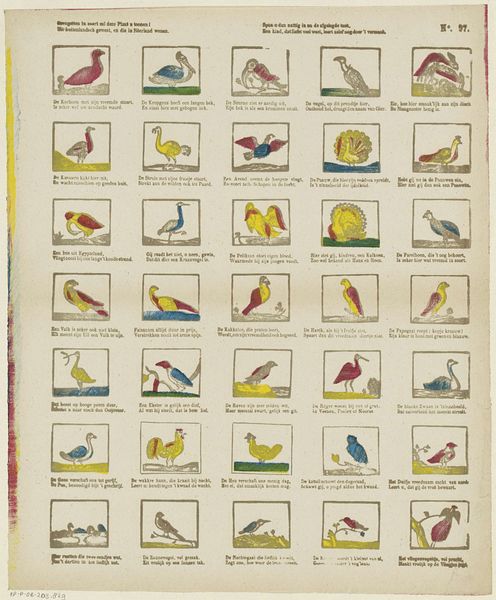

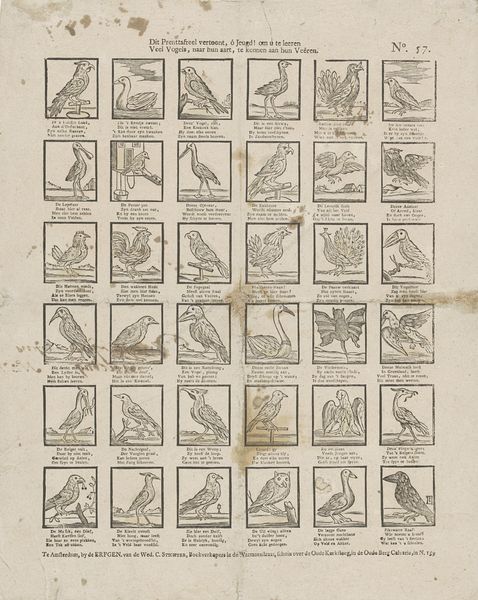

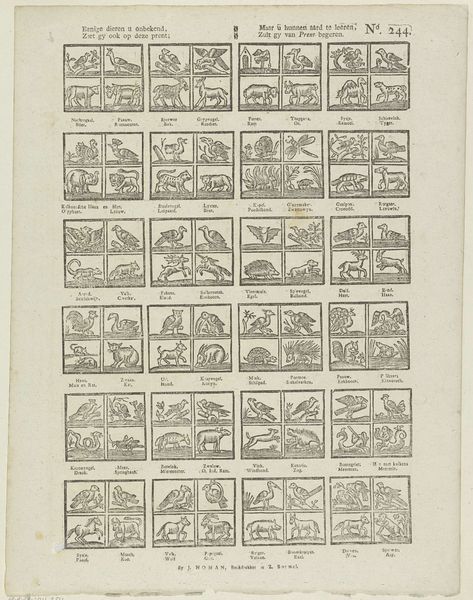

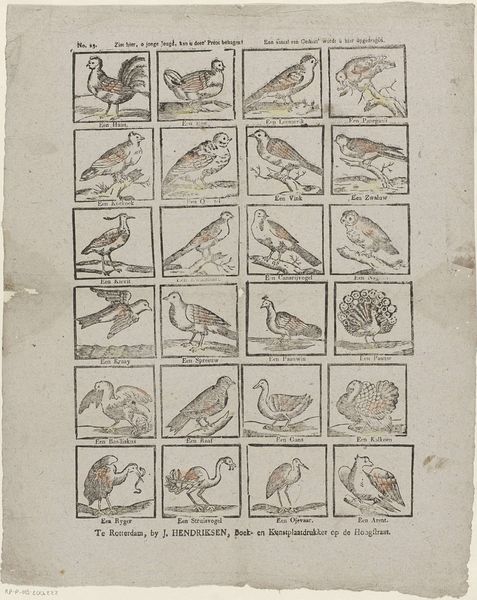

Velerhande vogelen, volgens alphabetische orde gerangschikt 1866 - 1902

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 429 mm, width 305 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us we have "Velerhande vogelen, volgens alphabetische orde gerangschikt", which translates to "Various birds, arranged in alphabetical order." It’s an engraving and woodcut, possibly with some hand-coloring, by Franciscus Antonius Beersmans, created between 1866 and 1902. Editor: Immediately I notice how these almost tile-like squares feel quaint, like something from an old storybook. Each bird feels like it holds its own little narrative world. There's a rustic simplicity, yet the alphabetical arrangement suggests order. Curator: I agree. Consider the sheer labor involved. Each tiny scene would have been painstakingly carved into a woodblock, inked, and then pressed. The addition of color, however minimal, adds another layer of manual work and possibly division of labor within the studio or workshop. Editor: That organization extends to symbolic order as well, wouldn’t you agree? Birds, in general, have a profound historical resonance across cultures—messengers, symbols of freedom, harbingers of change. Even the alphabetical order imposed suggests a structured understanding, perhaps aimed at a particular audience learning to read or identify bird species. Curator: That is a fascinating angle, and possibly indicative of this work serving an educational function within a specific social context. However, I am also curious about the availability and sourcing of materials like wood and ink at the time, and to what extent the artist participated in these processes. The level of craft expertise displayed clearly demonstrates sophisticated and specialized skill. Editor: Indeed, the details draw you in. But zoom out, and consider what birds symbolize—flights of fancy, connection to the divine, even the soul’s journey, and now look how contained in blocks they appear, regimented. Perhaps a commentary of some kind? Curator: Or maybe merely an attempt to classify and bring order to the natural world. Look closer at the printing process and you will find subtle variations suggesting wear and tear on the woodblocks or slight shifts in alignment during printing—revealing the human hand at work. This shifts the work away from being merely symbolic to having evidence of actual labor. Editor: I see that tension—order and freedom—and the birds, these small emblems, almost beckon for interpretation. They become coded images laden with cultural weight, making us look through a very specific cultural lens. Curator: So, while we may differ in our interpretive focus—materials and social context versus symbolism and cultural weight—perhaps we agree that Beersmans’ print serves as an intriguing object ripe with potential for both aesthetic and contextual appreciation. Editor: Absolutely, seeing it through your perspective helps emphasize the physical act of production alongside my exploration of encoded meanings within a work such as this, thus broadening our dialogue as such.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.