![[Man] by Hill and Adamson](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzL2U5MmJkNGExLTJiZmEtNDhiYy04YjZkLTlkZWM2MTNhNDI4MS9lOTJiZDRhMS0yYmZhLTQ4YmMtOGI2ZC05ZGVjNjEzYTQyODFfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

romanticism

Copyright: Public Domain

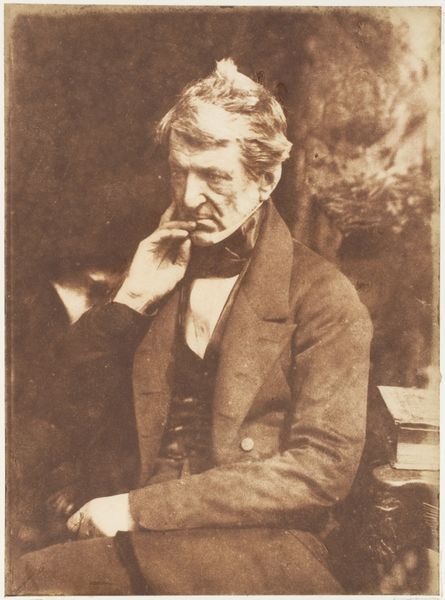

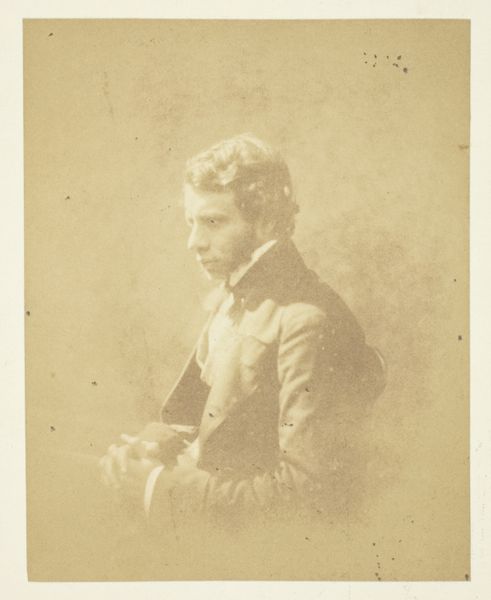

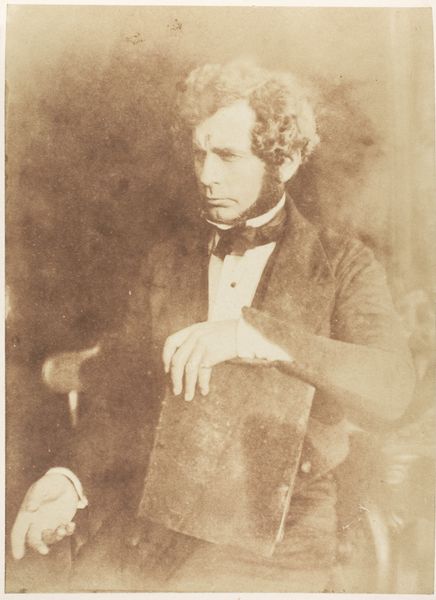

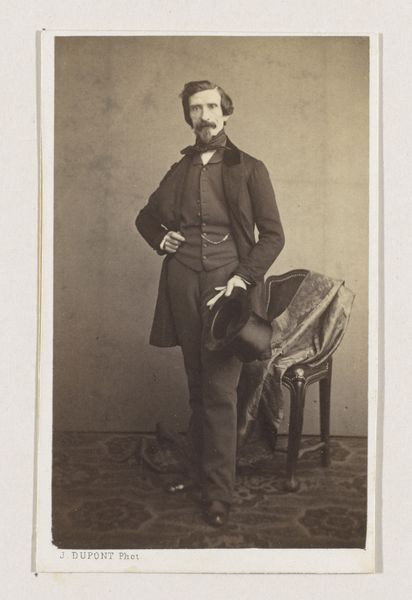

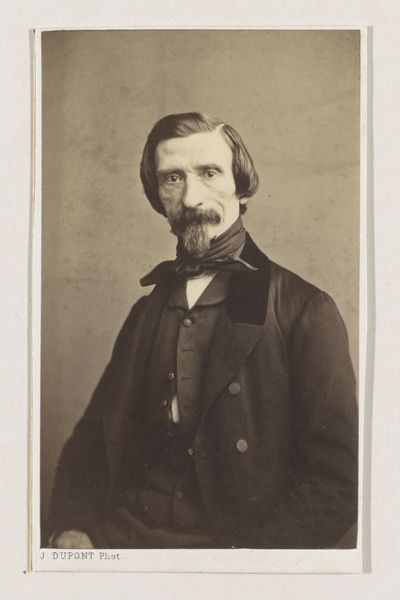

Curator: This daguerreotype, simply titled "[Man]", was captured between 1843 and 1847 by the pioneering Scottish photographers David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson. It's part of the Met's collection. Editor: The sepia tones lend it such a feeling of timelessness. He appears contemplative, lost in thought. There’s a quiet intimacy here. Curator: Hill and Adamson's work in the 1840s occupies an interesting place in art history. Photography was still a nascent technology. They used it both as documentation and artistic expression, particularly in portraiture, but as the latter we should still critically evaluate their process. Editor: Absolutely. I am curious about how portraiture can ever achieve objectivity; representation is a negotiation, not an exact reflection of the world as it appears. Look at his dress: the meticulous bow tie, the textured fabric of his jacket. How did he feel representing himself to these emerging photographic processes? Curator: These early photographs often demanded long exposure times, so the sitter had to remain very still, influencing the resulting compositions and, one might argue, dictating which subjects were even able to partake. Editor: I can only imagine what a privilege, or burden, this was for some people. Given the rarity of image making at the time, can we imagine he knew this would one day be displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art? Curator: The rise of photography as an accessible art form fundamentally changed how people saw themselves and their place in society, though, critically, we must remember who it gave access to, and how it challenged traditional notions of representation. Editor: And the role of museums in upholding this history—in carefully curating who is visible and how their images are consumed. Curator: Yes, institutions of art both influence, and are influenced by, social and political power, in a perpetual cycle of reform. Editor: Examining art like this is a mirror to examine both history and ourselves in our present, evolving moment.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.