Dimensions: 13 7/8 × 9 3/16 in. (35.2 × 23.3 cm) (image, vertical ōban)

Copyright: Public Domain

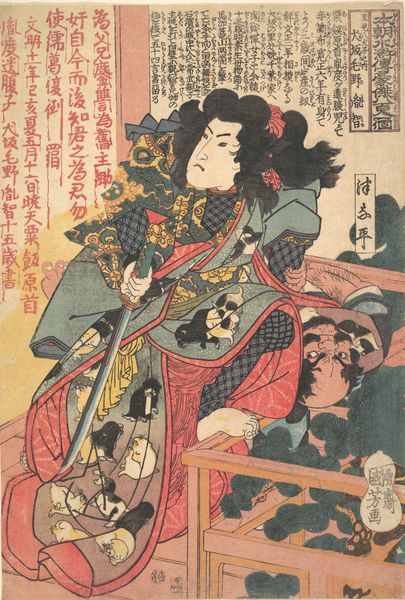

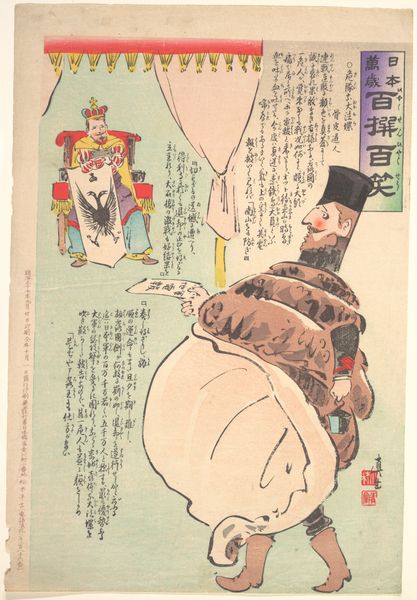

Curator: Wow, that expression alone could launch a thousand ships. Editor: Right? Kobayashi Kiyochika's "Blockhead," an ink and print on paper from 1894 and residing at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, screams of satire. The distorted figures practically leap off the paper. The contrast between the stern-faced Chinese figure and the bowing Japanese soldier… it's ripe with commentary. Curator: The "blockhead" himself… he looks so utterly unimpressed, even as he's holding, what is that, a tiny framed tiger? It's all so delightfully absurd. But I see something really sorrowful in the way it's rendered; the crude lines communicate his anger with the war, I presume. Or, he might just not be having a good hair day? Editor: Kiyochika, although working within the ukiyo-e tradition, frequently infused his work with political critique, especially concerning the Sino-Japanese War. Look closer—the caricatured features of the Chinese official, the guns haphazardly placed on the table, the forced deference of the Japanese soldier—it's a skewering of power dynamics and colonial ambitions. I see the tiger as a kind of perversion of a shared past. Curator: A skewering is spot on. It is hard to read, even by modern eyes; I am just fascinated with the odd details. The tiny canons feel too small to be a serious threat, but I get it's a comment on China. The man has a peculiar anger. And, by the way, look at the Japanese solider! What are these shoes doing in the tableau, on that table! I have so many questions. Editor: The disarray of the table, with those rogue shoes and scattered objects, adds to the sense of chaos and disrespect. The soldier is subservient and forced, the official cold, with the framed tiger adding a weird element of displaced exoticism or desire, while underlining China’s perceived status on the global stage during the era of imperialism. The chaos and weird elements certainly undermine what was considered honorable war. Curator: You know, it is pieces like these that I always go back to. Even in satire, truth rises like pollen to sting me in the face and, after all this discussion, what remains with me is the anger it manages to communicate even a century and half after it was created. Editor: Absolutely, the caricature is strong and painful. Despite the seemingly light-hearted style, it’s a potent reminder of the human cost of political maneuvering and enduring national wounds, of both nations involved. It’s also pretty weird that this conflict keeps getting reproduced again and again…

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

This woodblock series, created during the Sino-Japanese War (1894-95), reveals Kiyochika's political views and his fierce patriotism. To express his contempt for the Chinese and his support for the Japanese troops, Kiyochika collaborated with the writer Koppi Døjin. Here, the writer's comic text appears in a box in the upper part of the print. The man seated behind the red table represents the Chinese army at the Lushun Fortress, a historical stronghold in North China that was once believed to be impregnable. Calling it "blockhead," the writer and the artist applaud Japan's unexpectedly easy victory in taking Lushun.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.