photography

#

portrait

#

black and white photography

#

street-photography

#

photography

#

black and white

#

monochrome photography

#

monochrome

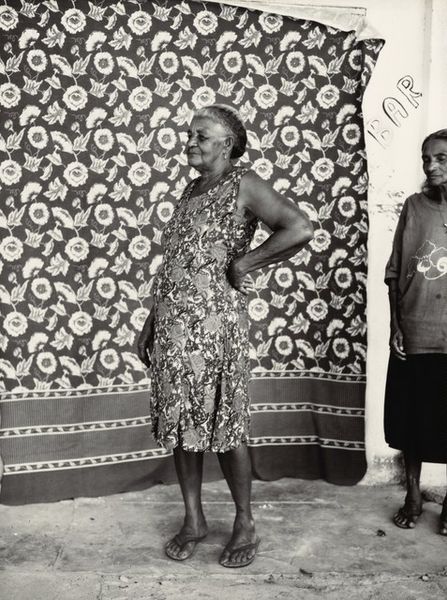

Dimensions: image: 14.1 × 20.4 cm (5 9/16 × 8 1/16 in.) sheet: 25.4 × 25.4 cm (10 × 10 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: This is a black and white photograph titled "Ramona Mack, Sacaton, Arizona" taken in 1966 by David Vestal. Editor: The composition is strikingly simple, almost documentary in its feel. The textures of the dress and the backdrop create a very subdued and natural environment, nothing grand. Curator: It's interesting that you mention the setting because Vestal's work often looks at the relationships between people and their everyday environments. He was less concerned with staged perfection and more about capturing a moment of real life as it was presented to him. This location gives us insight into Ramona's everyday environment. We know that Ramona was an Akimel O'odham woman living in southern Arizona in 1966. Editor: Yes, but looking closely, I see a negotiation between simplicity and deliberate construction. The shallow depth of field focuses our attention directly on Ramona while simultaneously positioning her within a specific geographic location with objects like laundry on a line behind her. He's composing a view on identity but also of labor. How was this work received in its own time? Curator: During this era, there was a growing interest in capturing "authentic" American experiences. But many images ended up simplifying, or worse, exoticizing marginalized communities. Vestal did make it a point to collaborate directly with his subjects, sharing prints and listening to their stories. Still, it is critical to acknowledge the power dynamics involved when representing communities one isn't a part of. We can only know the limitations of the artist. Editor: Agreed. We must also critically examine whose story we're telling and for what purpose. Considering photography's role in shaping public perception, the institutional circulation of these images would undeniably impact and even challenge dominant narratives. Curator: It also pushes us to examine the relationship between photographic practices, documentary ethics, and the construction of identity in the 1960s, prompting deeper inquiries into the historical contexts of visual representation. Editor: This makes you contemplate on who owns the story. Even through a photograph as a tool, ownership over a culture remains with its people.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.