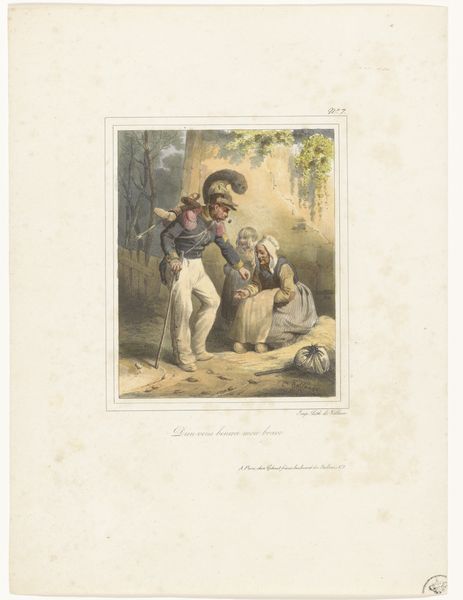

painting, watercolor

#

portrait

#

water colours

#

painting

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 240 mm, width 312 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

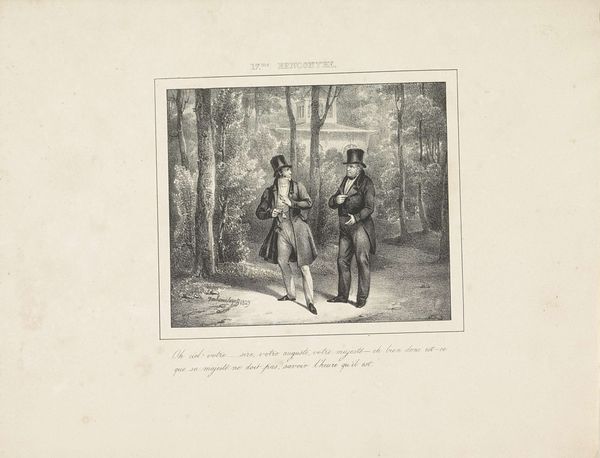

Editor: Here we have Jean-Louis Van Hemelryck’s 1829 watercolor, "Koning Willem I sprekend met een molenaar." It seems to capture a meeting between King William I and a miller, rendered in delicate strokes and a subdued palette. What do you see in this piece? Curator: Looking at this watercolor through a materialist lens, I’m struck by the choices inherent in its production. Why watercolor, with its associations with amateur art and the domestic sphere, to depict a king? How does the materiality of watercolor, a medium reliant on the dispersal of pigment in water, challenge the traditionally valorized oil painting in the representation of power and authority? Editor: That's interesting. So, the medium itself could be seen as making a statement about accessibility and perhaps even questioning power structures? Curator: Exactly. Consider the process of watercolor painting. It requires a lightness of touch, a fluidity, a certain acceptance of chance. In contrast to the perceived labor and "genius" associated with oil painting, watercolor was often taught to women of the upper classes as a social accomplishment. By employing it, the artist seems to subtly democratize the image of the King, bringing him down to earth, as it were, much like his conversation with the miller suggests. Also, we have to think about consumption: were these watercolors produced and acquired by a broad audience, expanding and shaping perceptions of royalty beyond the elite? Editor: That reframes how I see it. It's not just a historical scene, but a commentary on the means of representation themselves. The choice of watercolor makes me think of craft and its relation to social class. Curator: Precisely. It’s about interrogating the value systems embedded within art-making itself. We have to challenge those traditional boundaries between ‘high art’ and 'craft’ by examining labor, materiality, and consumption, even when looking at depictions of power. Editor: I never thought of it that way. Now I understand that analyzing the materials and processes is vital. It certainly provides another dimension of interpretation to the picture and shifts how you relate to the art. Curator: Indeed, paying attention to those elements gives access to understanding so much more than what meets the eye at first glance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.