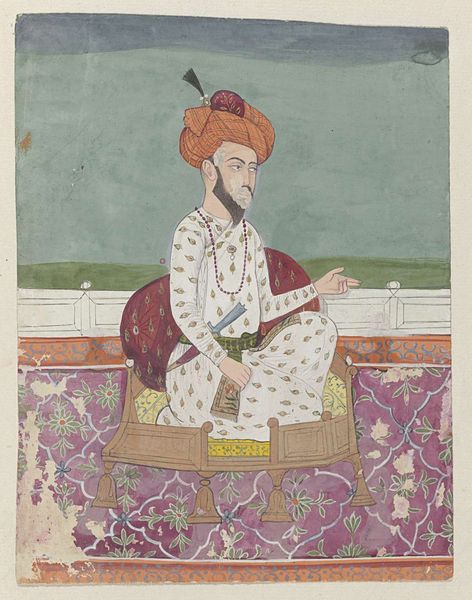

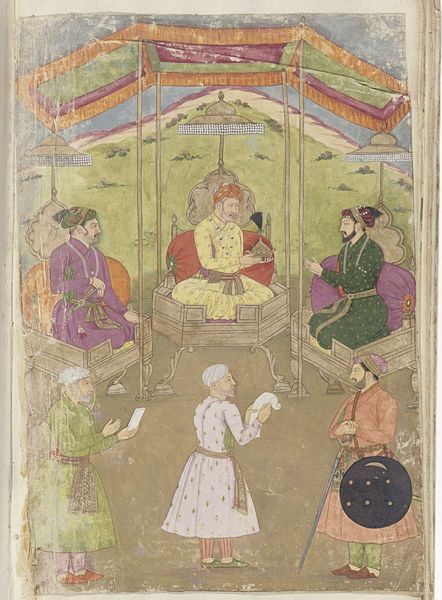

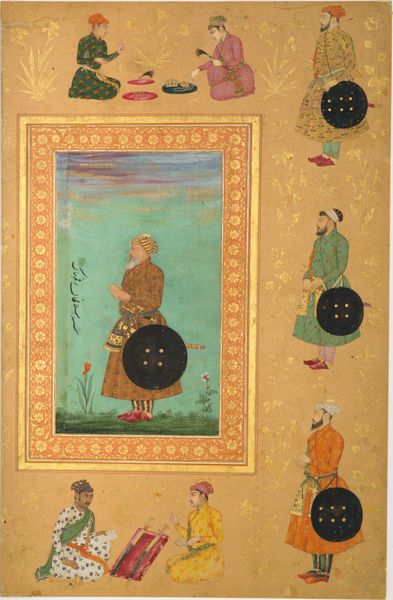

Dimensions: height 168 mm, width 132 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

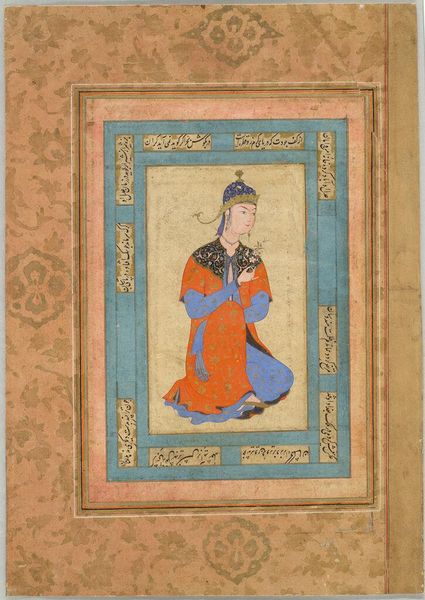

Curator: This exquisitely rendered watercolour is titled "Sultan Conrom," believed to have been created sometime between 1675 and 1755. Attributed to Adrianus Canter Visscher, it is an excellent example of orientalist painting. What strikes you first about this piece? Editor: I'm immediately captivated by the colours – the muted, almost dreamy quality, like a memory half-recalled. There's a gentle melancholy about it, even with the vivid oranges and blues. He appears, well, contemplative. Curator: Contemplative indeed. Note how the artist uses watercolour to capture the essence of the sultan’s bearing and regal pose. There is so much visual information here. He sits on an elaborate dais covered in fabric and pillows with what seems to be an attendant standing in the background, maybe? Editor: It’s that backdrop that gets me every time. Is that meant to be sky? Landscape? Garden? I think the flatness amplifies the symbolic weight of the figure himself. Those trees—they seem to hold symbolic relevance within both the Islamic aesthetic and broader historical portrayals of rulers and idealized landscapes. They seem almost… deliberate. Curator: Absolutely. Everything seems deliberate, a stage set where Conrom is both actor and emblem. It’s fascinating how Adrianus Canter Visscher combines precision and artistry, the intricate details versus the more symbolic renderings in this portrait. It definitely resonates within the context of miniature paintings and portraiture from the East at that time. Editor: This piece does remind us about how potent images are to convey identity. They’re rarely just a true reflection, but rather careful construction—a negotiation between power, cultural context, and individual personality. Do you get a sense the painter was attempting to impose western expectations onto this character? Curator: Certainly. The artist could never truly separate himself from his Western European viewpoint, try as he may, imbuing it with elements of "Orientalism," constructing the Sultan into what he wanted him to represent. A reflection not so much of Sultan Conrom, but of European desires, of long held fantasies. The whole composition oozes the visual tropes associated with rulers at that time. The seated posture is the same, no matter from West or East. The chair as the elevated "stage" for one figure. Amazing. Editor: Right? I am not so certain anymore. Looking closer, and despite the perspective, the cultural conversation becomes increasingly evident, offering not only insight but a mirror—a testament to how the symbols we weave, both individually and together, come to represent, affect, and even confine us. It goes beyond orientalism alone. Curator: That’s so interesting. This close examination certainly opened my eyes to see this painting in a very different light today. Thanks!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.