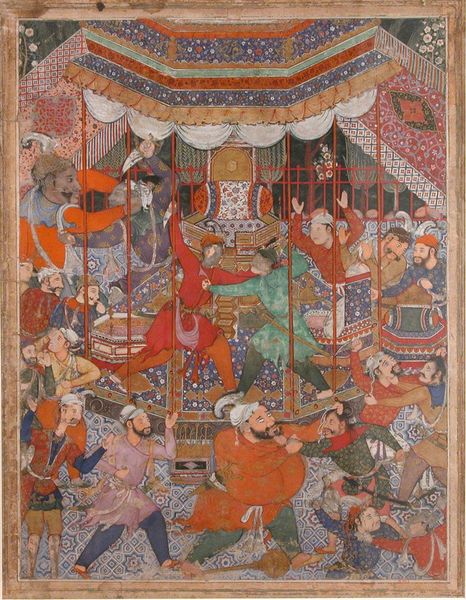

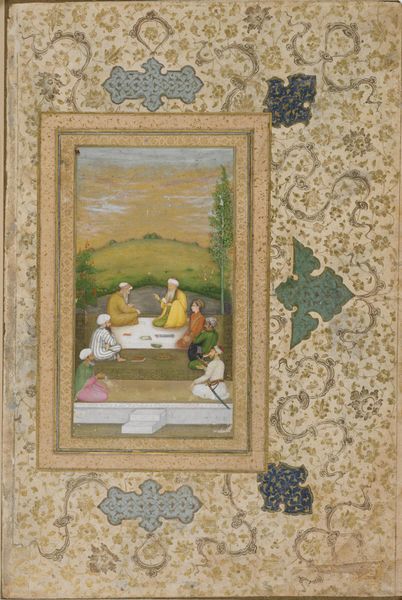

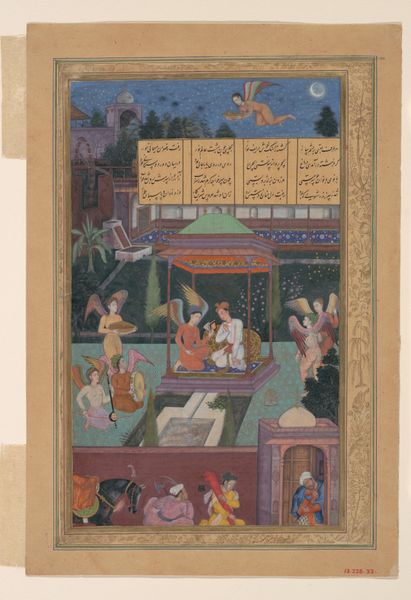

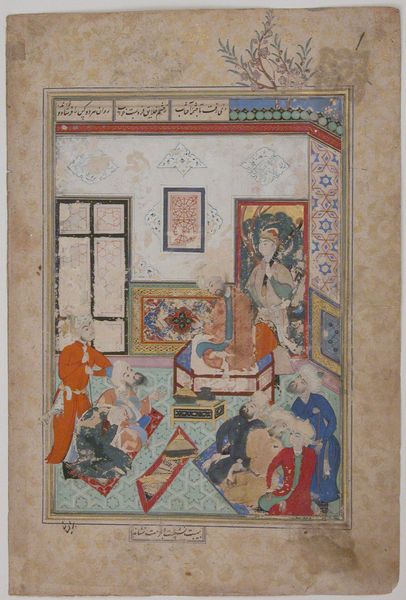

painting, watercolor, mural

#

portrait

#

water colours

#

painting

#

asian-art

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

geometric

#

traditional art medium

#

islamic-art

#

history-painting

#

mural

#

miniature

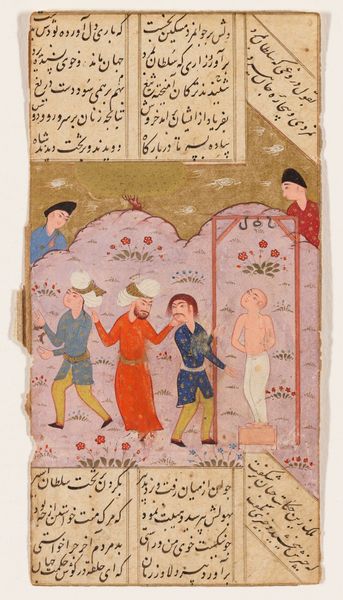

Dimensions: height 288 mm, width 195 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

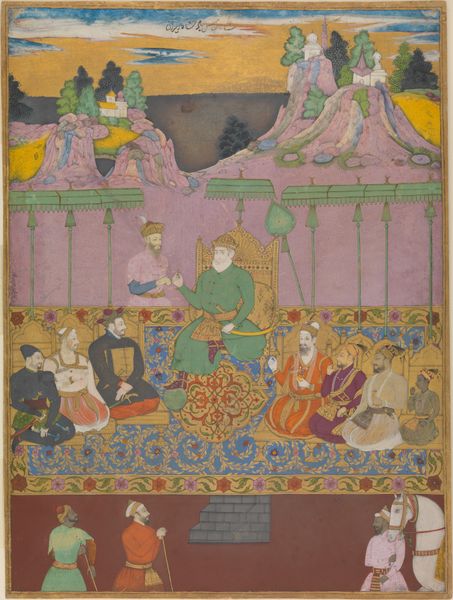

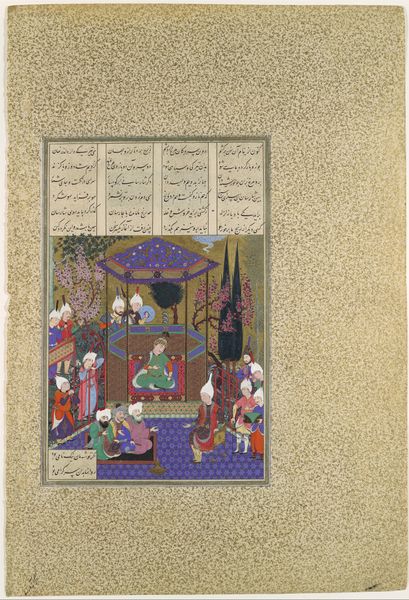

Curator: The composition strikes me as immediately formal, even theatrical. There's a definite sense of staged presentation, despite the muted tones of the watercolor and colored pencil. Editor: Indeed. We’re looking at "Prins Jehaan Badoun" by Adrianus Canter Visscher, made sometime between 1675 and 1755. This work, executed in watercolor, exemplifies a fascinating cultural dialogue that was taking place at the time. The artist was likely attempting to represent a specific type of non-European, and these images had very specific political uses. Curator: Absolutely, especially considering Visscher’s position. The politics of display here are quite intricate. How were these figures and this type of art received by its intended audiences? There's such deliberate composition, it’s not mere ethnographic curiosity, but deliberate construction of an image that circulated for specific reasons. Editor: Precisely! Miniatures like this one—though unusually large for the form—often functioned as tools of soft power, showcasing alliances and exoticizing distant realms for both local display, but, crucially, the West's expanding audiences. Look at the details – the geometry in the tent backdrop. These were designed to circulate visual symbols of authority, reinforcing Dutch power in a complicated global system. It shows how art acted within webs of political negotiation. Curator: So much hinges on how we unpack the portrayal itself. Take the central figure; we should unpack what his clothing choices say about his culture in relation to Dutch colonial perceptions. What are we subtly invited to admire or otherize in terms of aesthetic choices? The very act of translating cultural dress into a watercolor risks a simplification. Editor: The simplification itself speaks volumes about the prevailing Western gaze. There's inherent reduction when you transpose the complexity of Islamic or Asian power structures onto European paper using European artistic conventions. This risks turning the subject into a commodity of observation, feeding into a narrative of colonial knowledge. Curator: Ultimately, understanding the power dynamic behind the portrait's creation enables us to unravel not just art history, but social commentary on race and politics within 17th-century artistic traditions. Editor: It calls us to dissect those dynamics critically, seeing the art not as mere record, but as a stage upon which identity was being actively negotiated – and often contested.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.