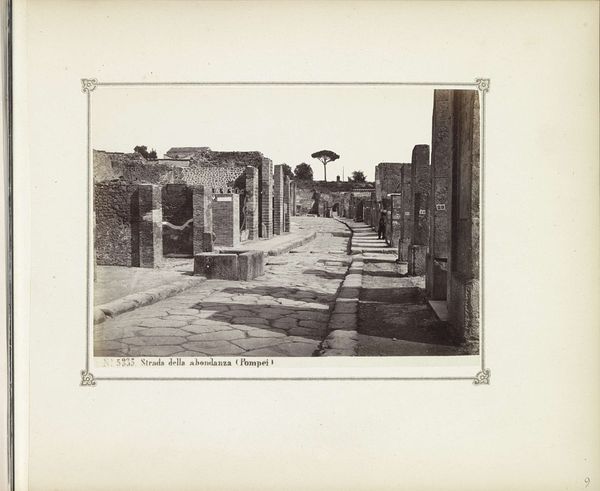

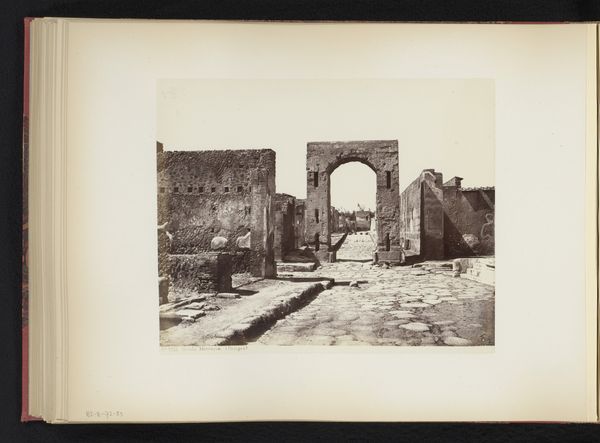

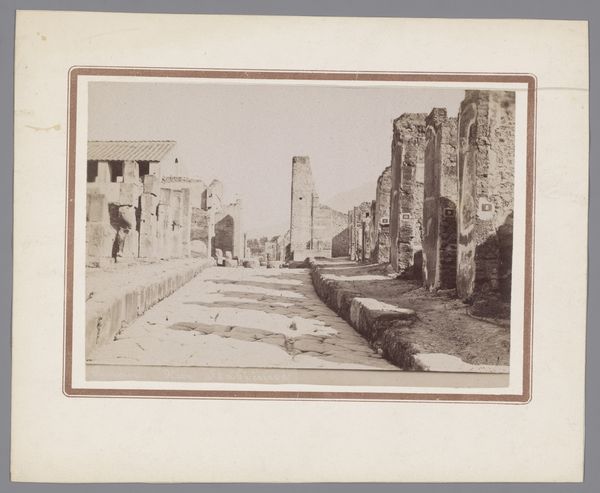

Restanten van gebouwen aan de Strada di Stabia in Pompeï c. 1860 - 1900

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

cityscape

#

street

Dimensions: height 107 mm, width 140 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

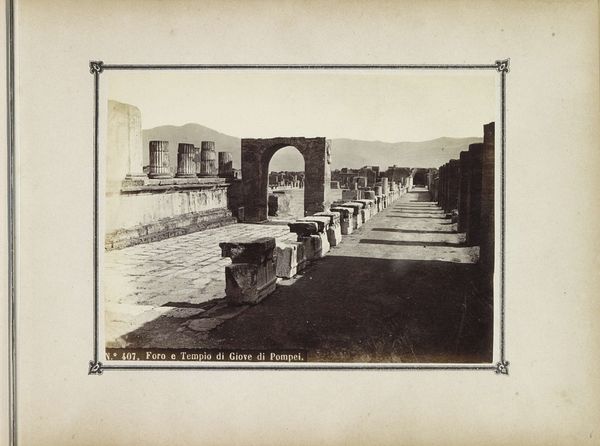

Editor: This gelatin-silver print, "Restanten van gebouwen aan de Strada di Stabia in Pompeï" by Giorgio Sommer, dating from around 1860 to 1900, shows the ruins of a city street. The rough textures of the stonework really strike me. What catches your eye in this photograph? Curator: For me, it's the social implications embedded within the image itself. This isn't just a pretty picture of ruins. It documents a specific moment of rediscovery and commodification. Consider the labor involved—from excavating Pompeii to producing and distributing these photographs as souvenirs. Who benefited, and what stories were left untold? Editor: So you’re saying the photograph isn't a neutral record, but a product of its own social context? The making of it tells a story? Curator: Precisely. The materials matter—the silver gelatin process itself enabled mass production and wider consumption. These images helped create a particular vision of Pompeii for the tourist gaze, often ignoring the realities of the excavation and its impact on the local population. Look at the way the street is framed; it invites the viewer to imagine themselves walking through, almost consuming the past. Editor: That makes me think about the labor of the people who originally built that street, the Roman workers... and how different that is from the labor that went into making the photo. Curator: Exactly. We need to ask: how did industrial processes and social hierarchies shape both the creation of Pompeii itself, and its subsequent representation? Who controlled the narrative, and who was silenced? Editor: It’s interesting to think about photography less as capturing a scene and more as another form of labor and consumption, with its own power dynamics. I’ll definitely look at photographs differently from now on. Curator: Seeing the making process and its underlying power structures changes the whole picture. It enriches our understanding of art, history, and society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.