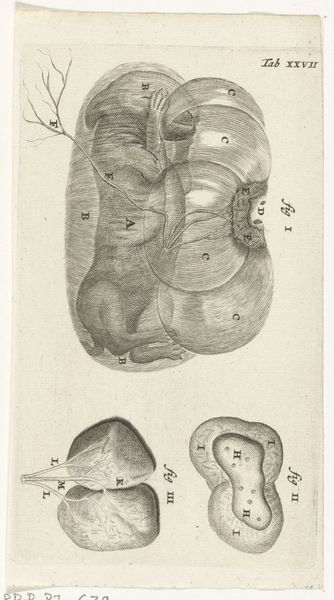

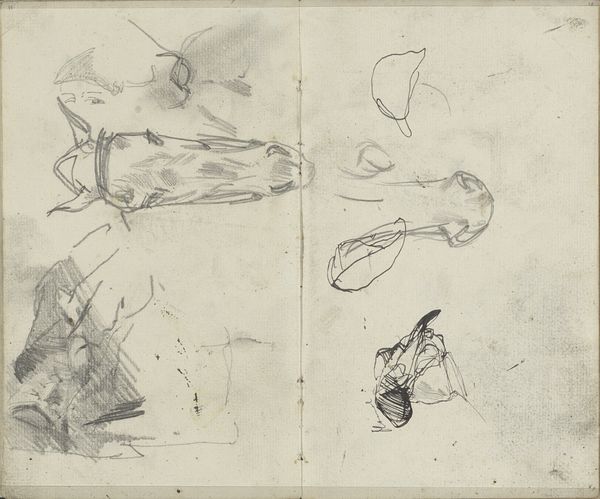

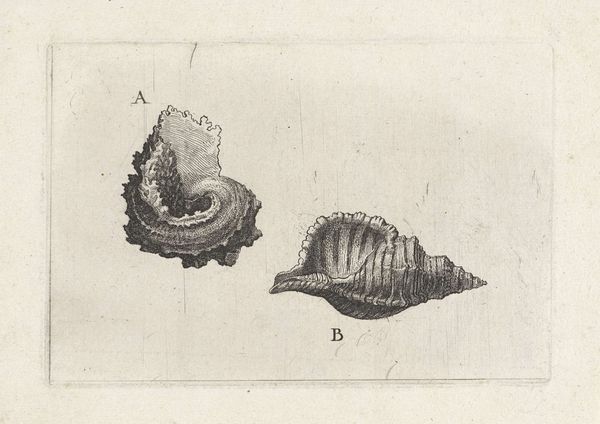

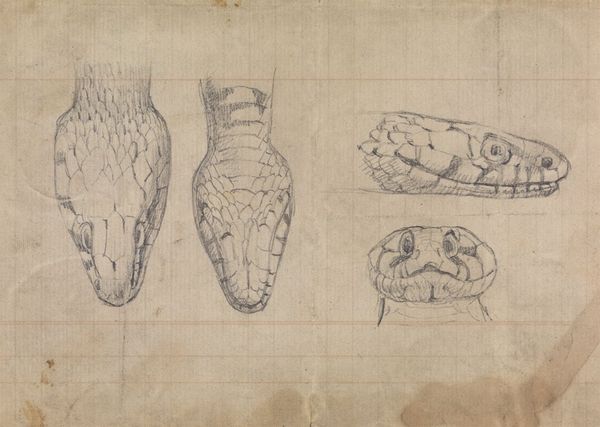

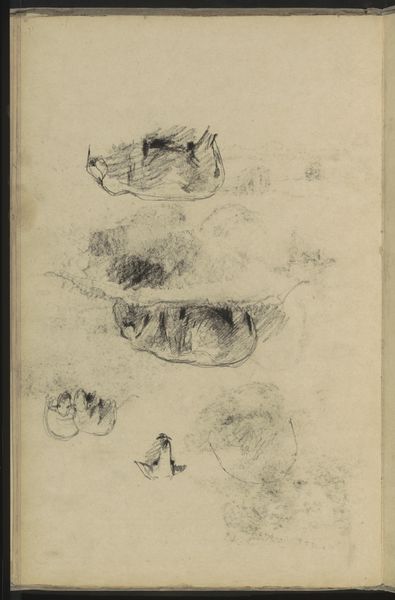

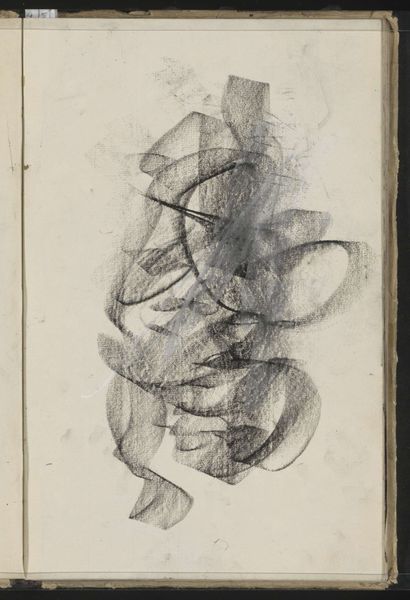

Hippopotamus amphibius (Hippopotamus), stomachs and intestines c. 1778 - 1779

0:00

0:00

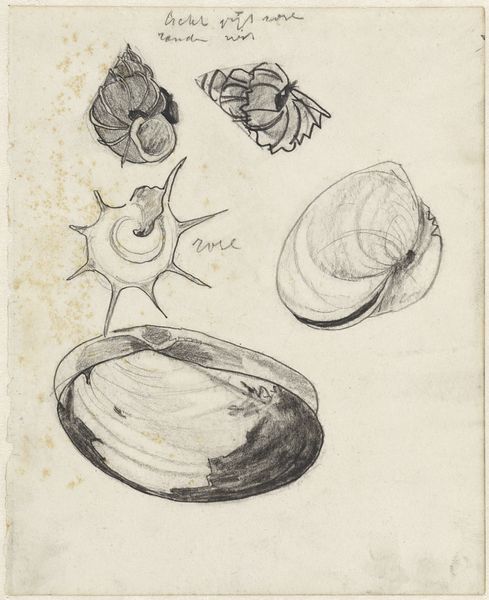

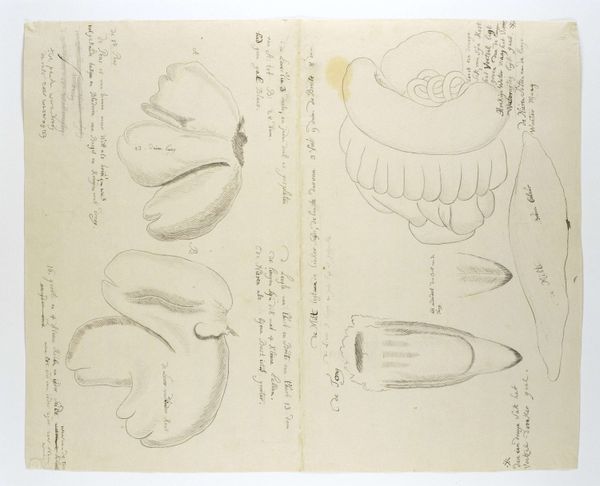

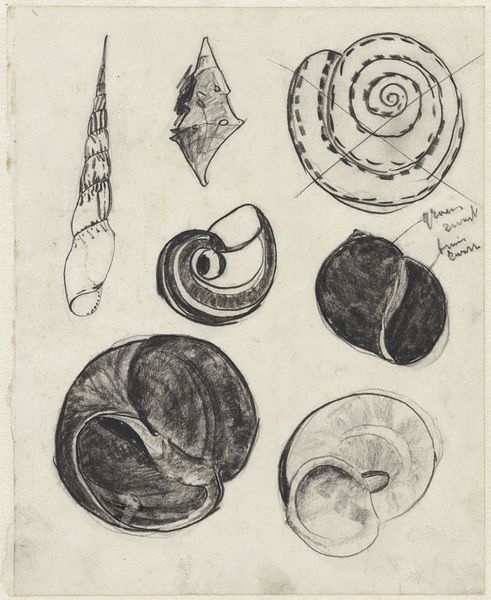

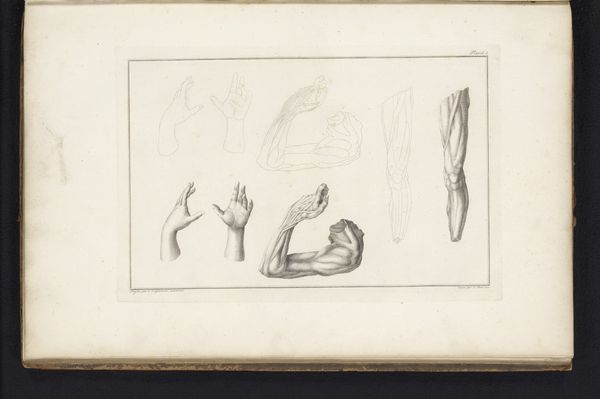

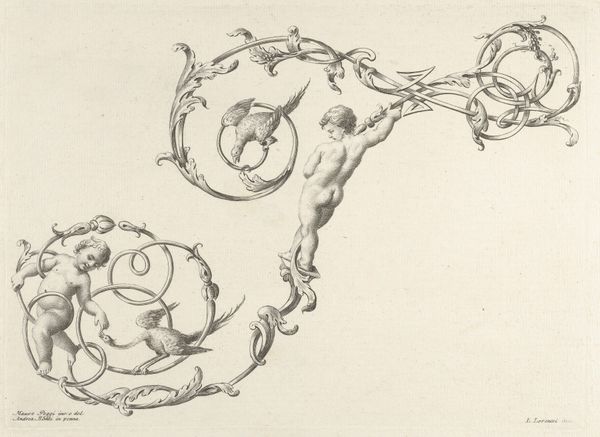

drawing, paper, ink, pen

#

drawing

#

pen sketch

#

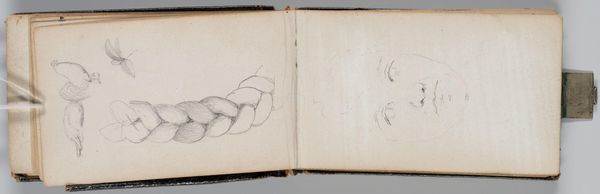

pencil sketch

#

paper

#

ink

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pen

#

academic-art

#

naturalism

Dimensions: height 660 mm, width 480 mm, height 316 mm, width 405 mm, height 157 mm, width 207 mm, height 158 mm, width 198 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: We're looking at Robert Jacob Gordon's drawing from around 1778-79, titled "Hippopotamus amphibius (Hippopotamus), stomachs and intestines," created with pen and ink on paper. It’s a strikingly clinical, almost detached, study of animal anatomy. What do you see in this piece? Curator: Beyond its representational aspect, I see a document deeply embedded in the history of scientific exploration and colonial expansion. Gordon was a military officer in the Dutch East India Company. How do you think his position influenced the way he rendered this hippo's anatomy? Editor: It probably speaks to a culture of meticulous record-keeping, part of claiming knowledge about the natural world for colonial purposes. It makes me think about power, like imposing order and understanding onto the unfamiliar. Curator: Precisely. Consider also the act of disassembling the animal for study. It reflects a specific kind of relationship – or perhaps, a lack of relationship – with nature, doesn't it? Was it destined to hang in a scientific institute or used for teaching, do you think? Editor: Maybe it was part of shaping a scientific and cultural identity in the colony? Defining its resources, even down to the guts of a hippopotamus. Did the distribution of such scientific documentation reflect socio-political agendas of that period? Curator: Undoubtedly. Think about who had access to this kind of knowledge, and what that meant for controlling resources and shaping narratives about the natural world. It represents a deliberate effort to categorize and classify nature. Editor: That context really transforms how I see the drawing. It’s no longer just a depiction of animal anatomy. I’m left considering broader impacts within the history of colonization and scientific endeavors. Curator: And hopefully it makes you reflect upon what types of stories about colonial settings are given precedence in our museum collections. We learn to understand not only Gordon’s methods of studying nature, but our own social lenses when looking at art today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.