De zelfopoffering van burgemeester Pieter van der Werff, 1574 1818 - 1876

0:00

0:00

carelchristiaanantonylast

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

16_19th-century

#

narrative-art

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

old-timey

#

19th century

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 374 mm, width 486 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

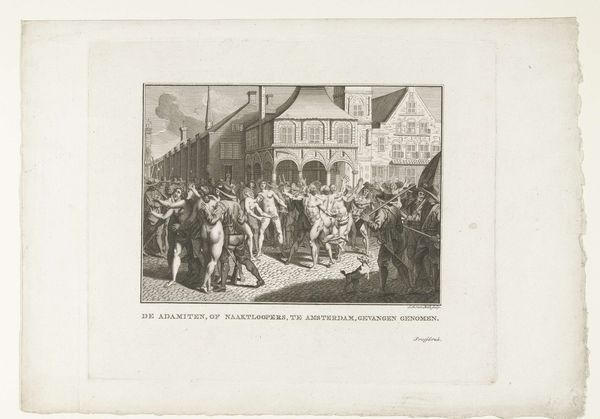

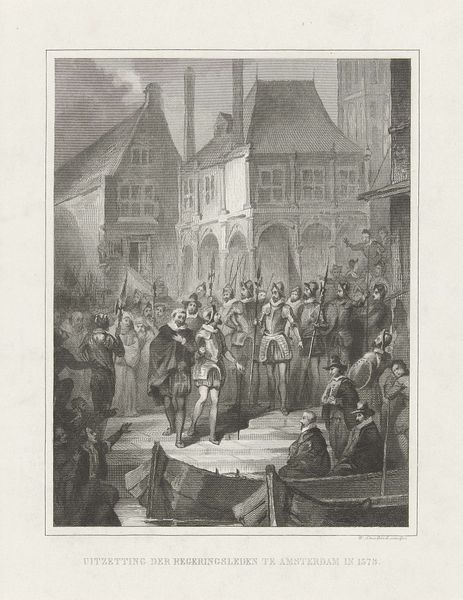

Curator: This print depicts Pieter van der Werff, the mayor of Leiden, during the siege of 1574. It's by Carel Christiaan Antony Last, and although he worked from 1818 to 1876, it portrays an event from much earlier. Editor: It hits you with such a bleak sense of… resignation, maybe? The high-contrast engraving style lends a dramatic, almost biblical, feel to the suffering. The sheer number of bodies makes your stomach clench, actually. Curator: The siege of Leiden was a key moment in Dutch history during the Eighty Years’ War. Van der Werff offered himself as food to his starving citizens to inspire them to resist Spanish rule. Of course, it was a grand gesture! Editor: An exceptionally theatrical gesture! And everyone else is so passive—prostrate, waiting… save for a handful of figures in the background watching the supposed sacrifice. How constructed do you think Last’s interpretation of this event is, really? Is it glorification or critical assessment? Curator: Both, I believe. Remember, this was created during a period of rising Dutch nationalism. History became a battleground for constructing a shared identity. Van der Werff became a symbol, this visual testament aimed at creating national sentiment around civic virtue, even in dire circumstances. Editor: Interesting. The inclusion of that specific church steeple dominating the background really ties the event into a sense of place and permanence. Were cityscapes popular motifs back then, considering the print was designed in the 19th century while representing a 16th-century siege? Curator: Indeed. The choice to place this historical drama within the easily recognizable city of Leiden reinforces a tangible connection to the past for the contemporary viewer. But to the point of constructing meaning – yes. In prints such as these, historical accuracy is second to political efficacy and nation-building. Editor: It really underscores how art doesn't just reflect history; it actively molds our understanding of it, doesn't it? This little piece serves a rather bigger, politically influenced, story than simply the mayor and his offering. Food for thought… if you could find any! Curator: An astute observation. Consider how this image, distributed as a print, had the power to galvanize sentiments and shape historical consciousness at a critical juncture in Dutch nationhood.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.