silver, print, daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

silver

# print

#

war

#

landscape

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

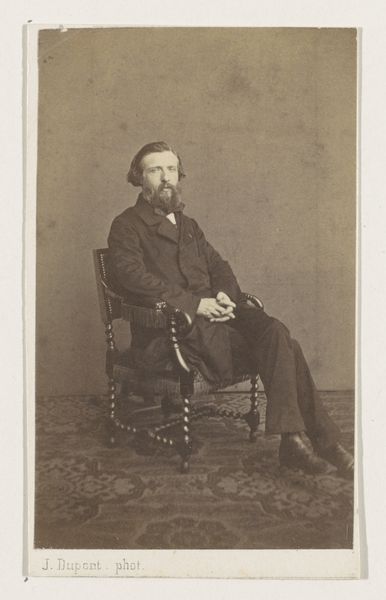

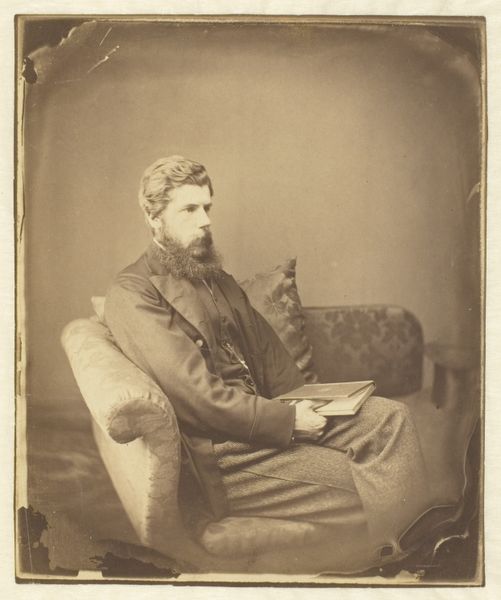

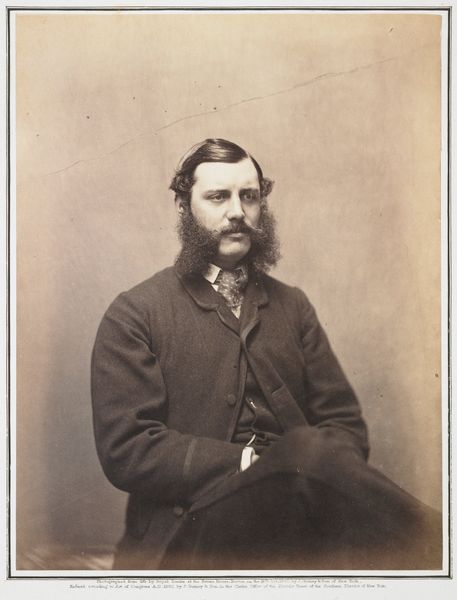

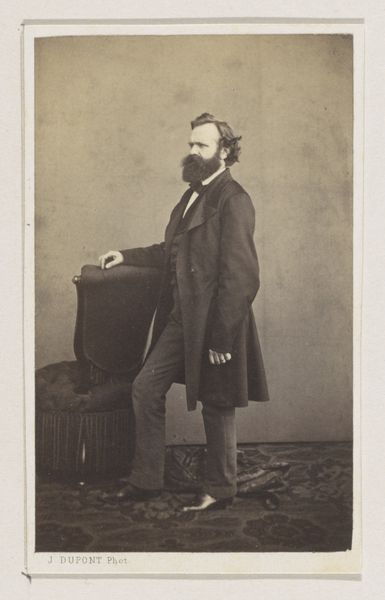

men

Dimensions: 27.2 × 22.4 cm (image/paper); 33 × 23.3 cm (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

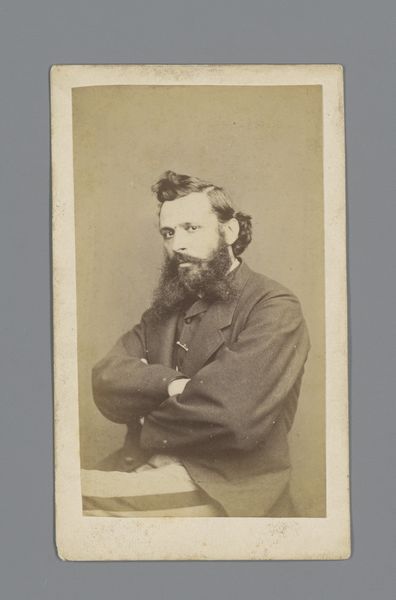

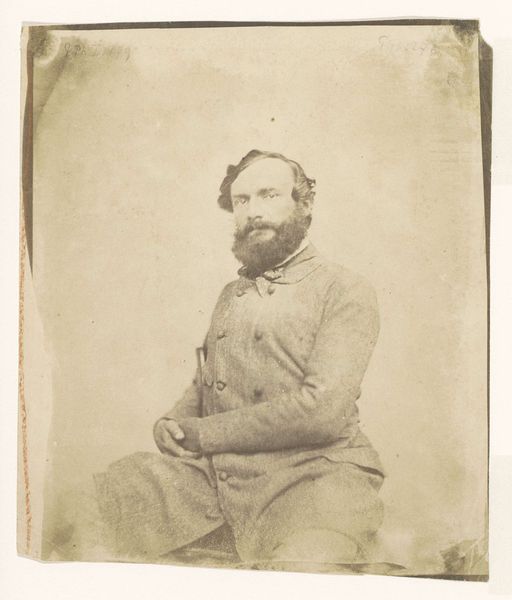

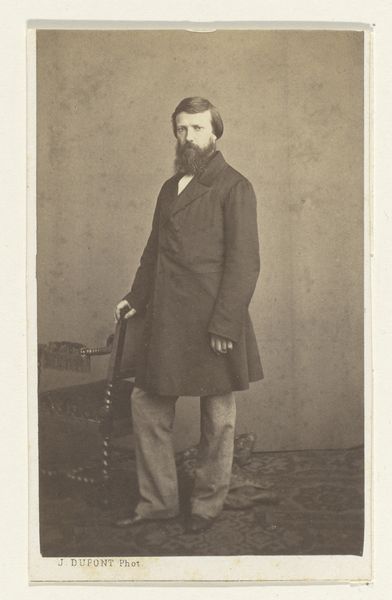

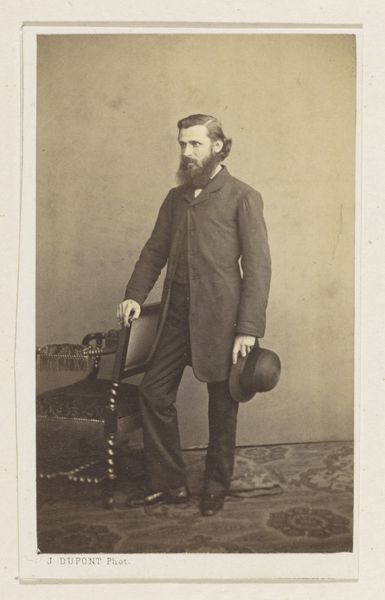

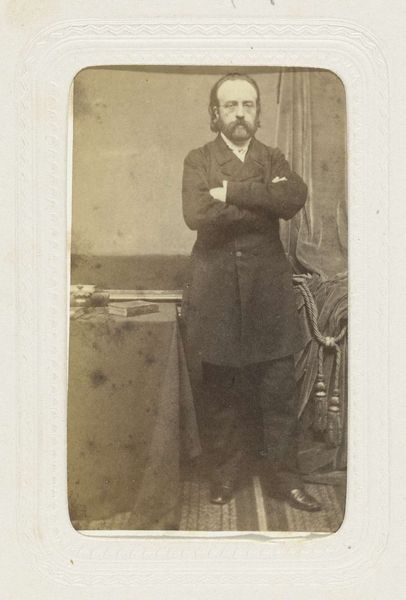

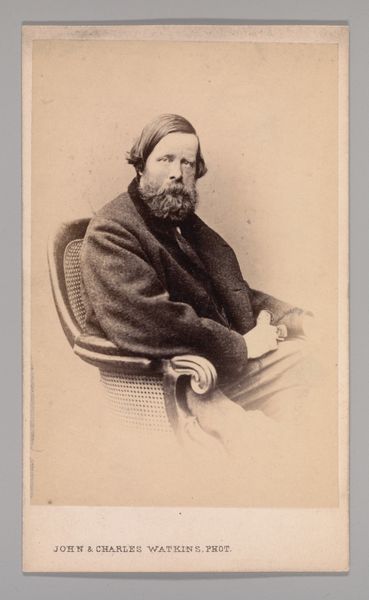

Curator: Gazing intently, we see Colonel Simmons, attaché to Omar Pacha, in this 1855 photograph by Roger Fenton. Something about the starkness… It feels intensely present, doesn’t it? Editor: Bleak. That's the first word that hits me. The heavy, almost suffocating texture of his coat contrasted with the bare photographic process itself. I mean, the limitations inherent in that early silver print just emphasize a brutal sort of honesty. Curator: Brutal honesty, yes. It lacks the romanticism of some war imagery; you sense the weight of it. Fenton, though on assignment during the Crimean War, captures this detached observation so eloquently, really sidesteps all those trappings. Editor: Absolutely. And consider Fenton's choice to primarily photograph the officers, rather than the battlefield's devastation. It brings up a discourse around class and access to representation at the time. Like, whose story gets told and how is it being constructed? Curator: It certainly makes you ponder about power dynamics during wartime, who had a voice. And Fenton’s skill in rendering texture…look at how the light catches the woolen fabric of his overcoat, hinting at cold weather realities beyond superficial portrayals of battle. He seems utterly self-contained. Editor: I'm also stuck on the material constraints that made the portrait possible in the first place. Think of the silver, mined, processed, manufactured into photographic plates. Then, consider the labor involved. It adds an invisible layer of complexity to our reading, all those unseen hands and efforts involved. Curator: Absolutely. It’s funny; sometimes these static images feel like the start of a story more than the encapsulation of one, if that makes sense. We see what the lens shows but imagine endlessly, what existed just beyond its narrow capture. Editor: Yeah, in this portrait you get the impression that we're seeing just one sliver of someone deeply involved within a wider chain of events, mediated by complex social, material, and historical processes. It reminds me of the sheer, often overwhelming amount of *stuff* connected to conflict. Curator: So true. It definitely compels consideration that photography isn't some clean, objective recorder. Rather, it represents labor and choices made. I feel as though that changes everything as we observe images from that war and time period. Editor: Agreed, an examination that forces you to consider broader historical making beyond the content itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.