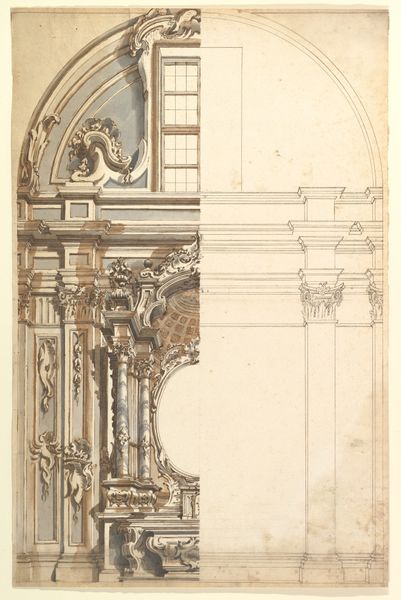

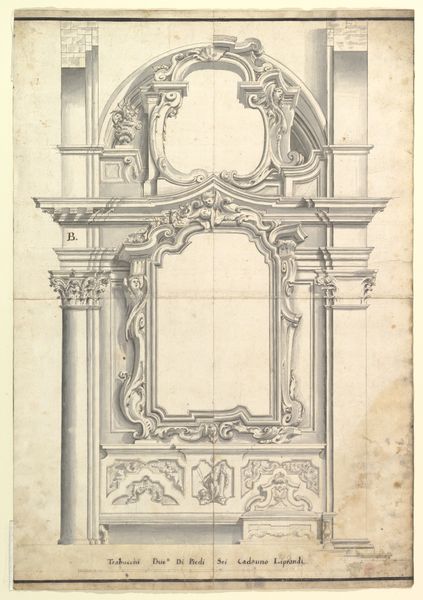

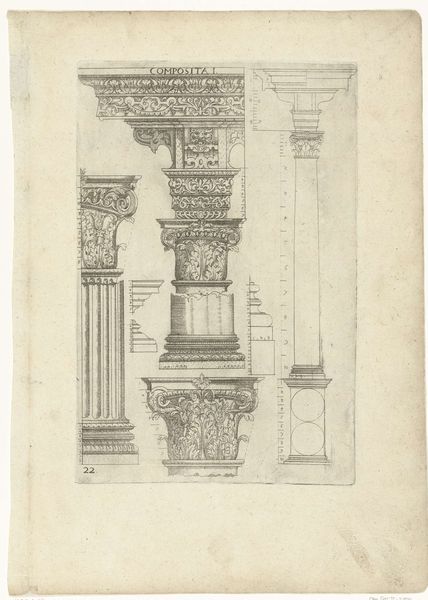

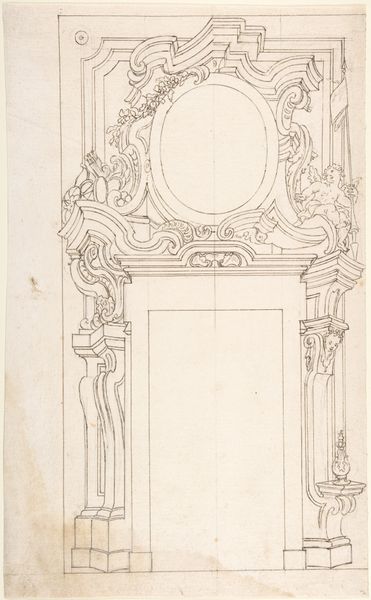

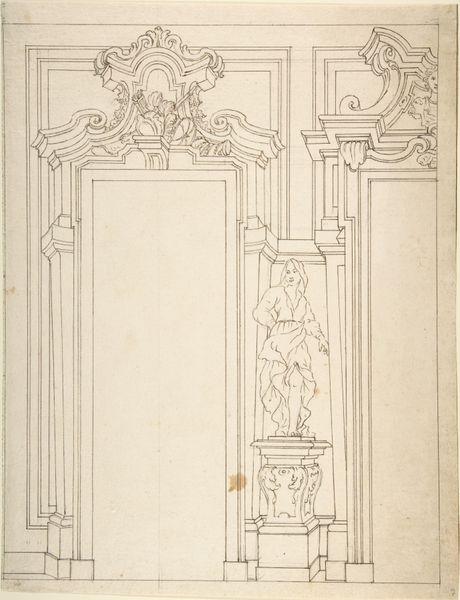

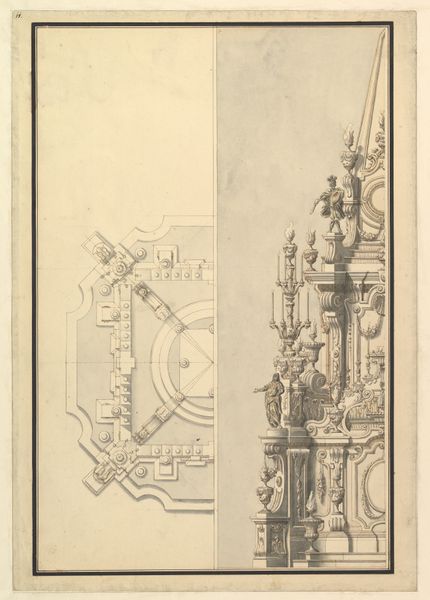

drawing, print, pencil, architecture

#

drawing

#

baroque

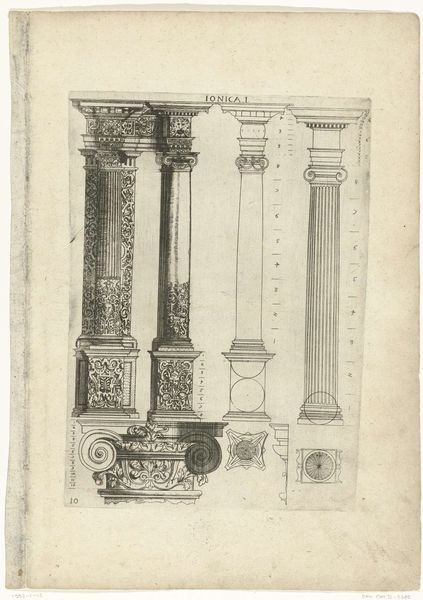

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

etching

#

perspective

#

pencil

#

architecture

Dimensions: sheet: 22 15/16 x 10 7/16 in. (58.2 x 26.5 cm) = 58.2 x (26.5+3.2) cm. (3.2cm folded right border)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is an interesting preparatory drawing, "Halved Design for an Altar in a Chapel," dating from between 1700 and 1780. It's a pencil and etching print by an anonymous artist and resides at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It has an unfinished look to it, and seems to privilege structure, even architectural elements, over overtly religious iconography. How do you approach something like this, which seems to focus so much on design? Curator: It’s crucial to consider the means of production here. This isn't a finished altarpiece but a design. It’s about the labor, the skill required to translate an architectural vision onto paper with pencil and etching, tools accessible to a wider range of artisans beyond marble sculptors. Note how the etching creates subtle tonal variations mimicking the light and shadow crucial in baroque architecture. Think about the social context: who was commissioning such designs and why invest in elaborate sketches? Editor: So it’s less about the religious function and more about...the demonstration of skill or planning the logistics of building? Curator: Precisely. The focus shifts from spiritual contemplation to material construction. This print flattens what will be a 3-dimensional and immersive spiritual space; it reduces it to consumable commodity for the patron. We need to examine the availability and cost of materials at the time – how would the stone and building material have been transported? How would labor have been divided? Editor: It almost democratizes the process, right? Anyone could, theoretically, possess this image and dissect its creation… or at least consider the possibilities inherent in it. Curator: Absolutely. This also reflects a changing social dynamic, potentially catering to a wealthier, non-aristocratic clientele who desired similar displays of piety and status. By examining the lines, the etching technique, and even the paper itself, we can glean insights into 18th-century consumption patterns and the art market. Editor: I never considered how a preliminary drawing could reveal so much about society! That reframes my entire approach to pieces like this one. Curator: Understanding the materiality behind art gives us more tools to explore not just what something is, but how it came to be.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.