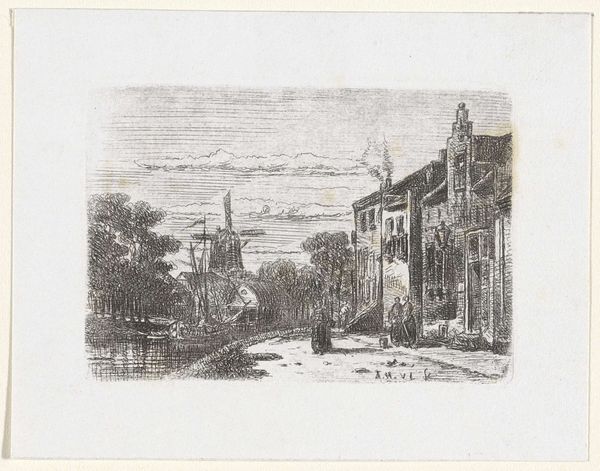

print, etching, engraving

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

etching

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

form

#

line

#

cityscape

#

engraving

#

realism

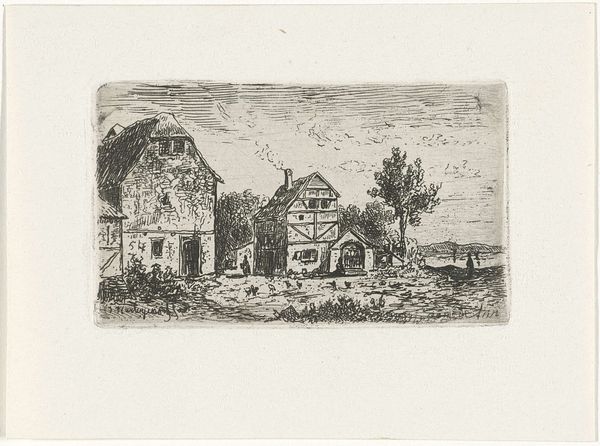

Dimensions: height 140 mm, width 216 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is Isaac Weissenbruch’s “Stadsgezicht te IJsselstein,” an etching dating between 1836 and 1912. The texture and contrast are really striking. It makes me wonder about the relationship between the buildings and the water, especially given the figures almost hidden in the shadows. What do you see in this piece beyond just a cityscape? Curator: What strikes me immediately is the contrast between the detailed rendering of the buildings and the more ambiguous depiction of the people within the landscape. I see an exploration of visibility and invisibility. The figures, possibly women, seem almost swallowed by the architecture, reflecting perhaps the limited agency historically afforded to them within the public sphere. Do you think that tension is deliberate? Editor: I hadn’t considered that, but it does feel intentional. The sharp lines defining the buildings contrast sharply with the blurred figures, making them almost blend into the stonework. So, are you suggesting the image subtly critiques societal structures of the time? Curator: Absolutely. Landscape art isn't simply about pretty scenery. It’s often a reflection—or a subversion—of prevailing power dynamics. Weissenbruch positions these buildings, these structures of authority, in stark relief against figures potentially marginalized. It encourages us to question who has the privilege of being seen, being heard, being recognized. Who defines that visual space? Editor: That completely reframes my understanding. The city scene isn't just picturesque; it’s a loaded stage. Curator: Precisely. Think about how this piece might resonate today, as we still grapple with issues of representation and the ongoing struggle for visibility for marginalized communities in urban environments and artistic narratives. Editor: I’ll never look at a landscape the same way again. Thanks for opening my eyes to this powerful dimension. Curator: My pleasure. Art history is constantly speaking to the present, if we're willing to listen critically.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.