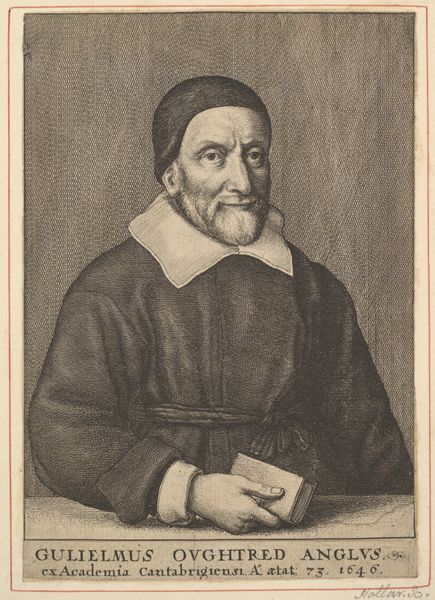

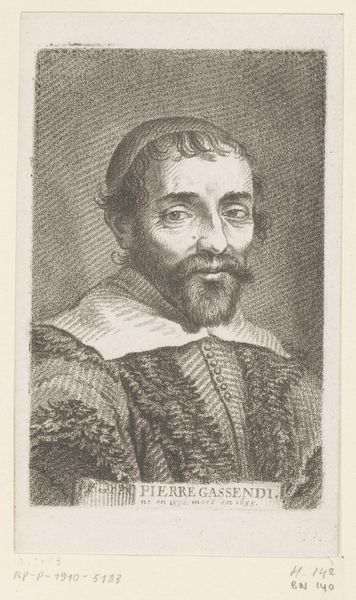

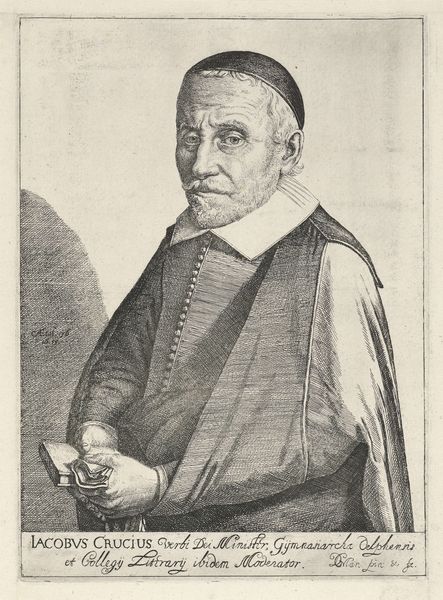

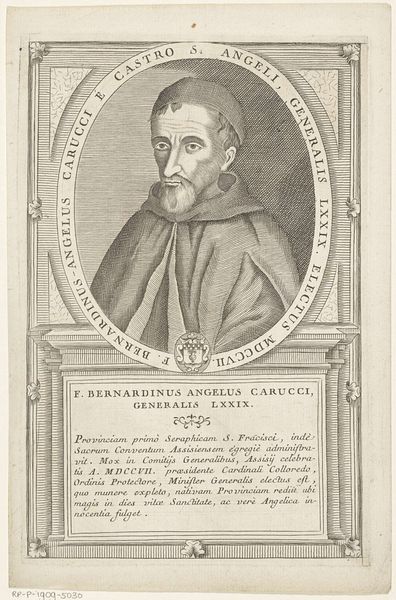

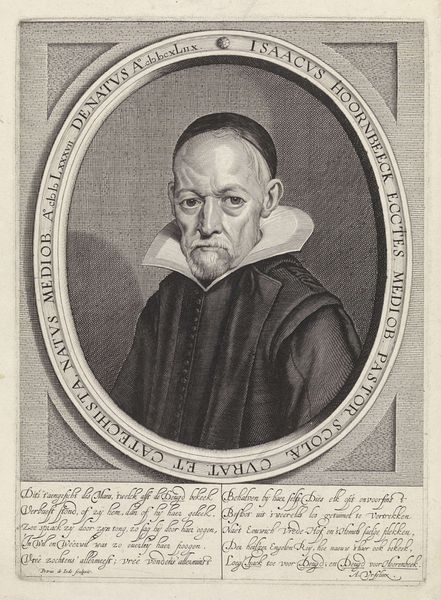

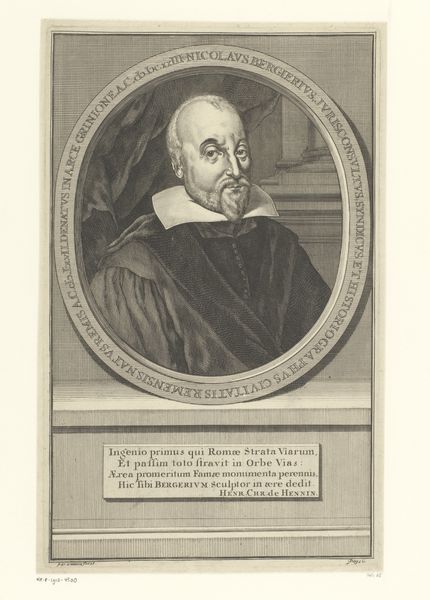

drawing, print, etching, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: plate: 7 9/16 x 4 7/16 in. (19.2 x 11.2 cm) sheet: 7 13/16 x 4 5/8 in. (19.9 x 11.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Let’s turn our attention to this etching, "Portrait of John Diodati," crafted in 1643 by Wenceslaus Hollar. It resides here with us at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. What strikes you initially about this historical image? Editor: The man's piercing gaze holds such authority, yet the etching itself, despite the intricate detailing of his clothes, feels somewhat austere, doesn't it? There’s a sense of constrained power, of intellect tempered by the gravity of his position. It projects such strong messages. Curator: Indeed. The subject, John Diodati, was a renowned Calvinist theologian and translator. Hollar made this work, when Diodati was 66. As the inscription states, Diodati was a Minister of God's Word in Geneva. This piece captures a moment in the history of religious and intellectual life. Editor: That context enriches the piece considerably. Knowing he was a translator inflects the way he holds the book. His very posture and bearing communicate conviction, as if every line etched on his face speaks to years spent wrestling with theological concepts. His race, class and role as a minister certainly play a huge part of this narrative. Curator: Precisely. And the meticulous detail Hollar employs contributes to that sense of conviction. The textures of his robes, the precision of his features – these aren't merely aesthetic choices. They reinforce Diodati's presence, his importance within the religious and social structure of his time. Editor: It prompts me to consider, then, for whom was this image created, and what purpose did it serve? Was it meant to inspire devotion, solidify his influence, or document his likeness for posterity, reinforcing existing power dynamics? Curator: All those purposes, likely intertwined. Printmaking at this time served as a powerful means of disseminating images, bolstering reputation, and projecting specific ideas about leadership and authority across a wide audience. Editor: Absolutely. I’m drawn, also, to reflect on the idea that this image—so precisely rendered—nevertheless represents a single, constructed perspective of the sitter, one that elides his potential contradictions and interiority, while promoting a narrative of Protestant leadership. The artist only had his truth to rely upon. Curator: That’s a crucial observation. Thinking about representation is fundamental to the artwork. Editor: Exactly. By focusing on its political, social and historical meanings we move past seeing art as only an aesthetic experience and use it as a powerful tool. Curator: And with those fascinating insights, we leave our audience to consider the legacy of the Reverend John Diodati and the society of which he was a product.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.