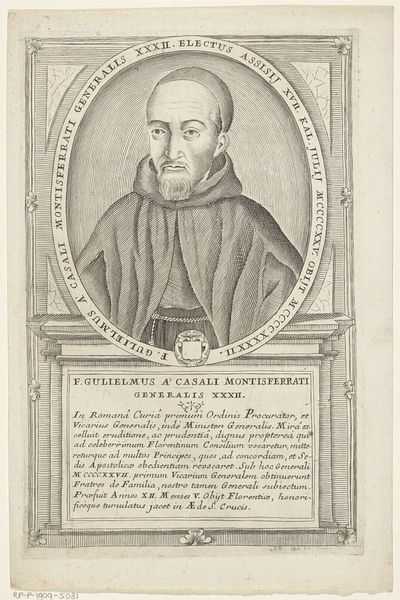

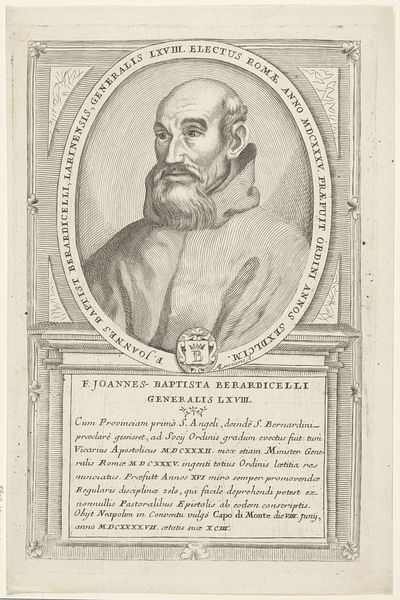

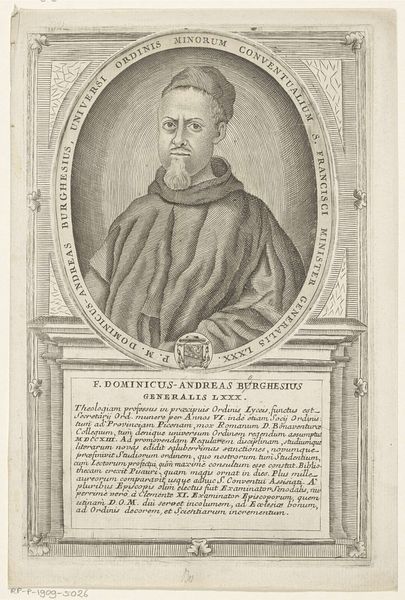

Portret van Bernadino Angelo Carucci, 79ste Minister Generaal van de franciscaner orde 1710 - 1738

0:00

0:00

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 252 mm, width 165 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this rather formal portrait, we see an engraving, made between 1710 and 1738, depicting Bernadino Angelo Carucci. The inscription tells us he was the 79th Minister General of the Franciscan Order. It's attributed to Antonio Luciani. Editor: It feels so severe, doesn't it? The tight lines of the engraving, the close cropping, the unwavering gaze… there’s little softness. It’s like an official document more than a likeness. The Latin script surrounding the image reinforces this feeling of authority. Curator: Precisely. The Baroque era, especially within the Church, used imagery strategically. Printmaking allowed for wider distribution. This image, therefore, likely served to disseminate and solidify Carucci's authority within the Franciscan Order and beyond. The text celebrates his service. Editor: I wonder about the accessibility. Who exactly would have understood the Latin inscription? Was it primarily for other clergy or members of the elite, further reinforcing existing power structures? The language itself seems to act as a barrier, keeping Carucci conceptually out of reach for the masses. Curator: It highlights the layered nature of such imagery. The portrait would offer a recognizable face, while the inscription details his virtues for a more learned audience. This portrait is one component of a carefully constructed image. It served multiple roles. Editor: Yes, but also it hides so much. I’m struck by how the material reality of religious life—the struggles of the poor, the complexities of faith—is almost erased here. It presents a sanitized, powerful figure rather than an embodied person embedded within a socio-economic structure. Curator: We might consider this a representation, crafted for public consumption rather than necessarily a 'true' likeness. The details within the engraving—the patterns on his robes, the specific lines chosen—are all purposeful. Editor: What does this portrait leave out of the frame, both visually and contextually? Analyzing art means examining its calculated elisions. It pushes me to think more about the other stories— the un-engraved experiences surrounding religious institutions and the social function of portraiture at the time. Curator: Absolutely. It encourages one to dig beneath the surface to uncover social functions that these artifacts of history served. Editor: Well put, a single image invites us to think about layers of power and purpose behind every printed image.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.