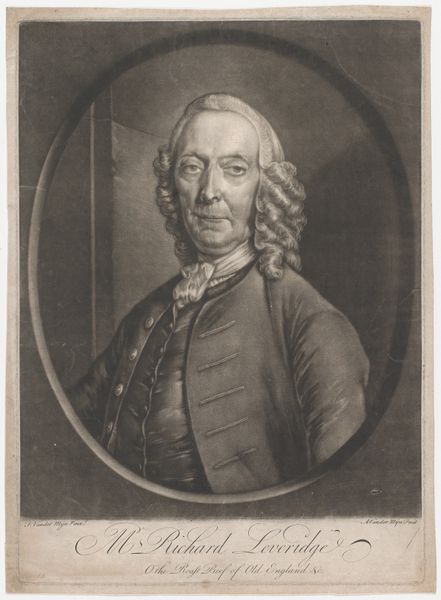

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 327 mm, width 228 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

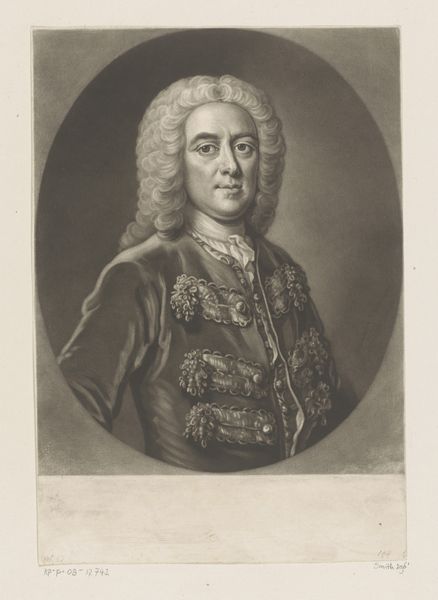

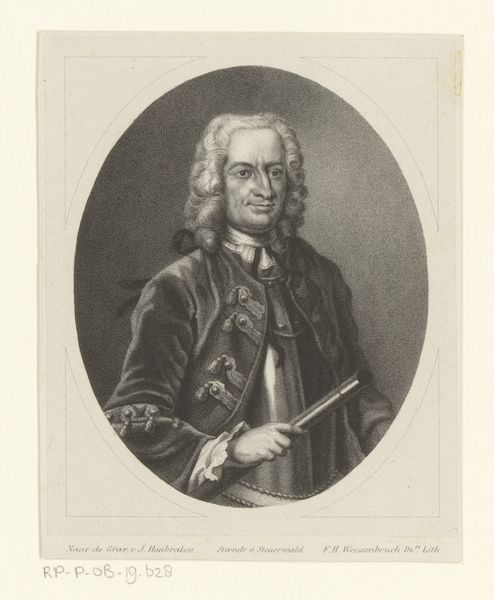

Curator: This engraving, titled "Portret van John Coutts," dates back to between 1751 and 1753. It's by James McArdell and currently resides here at the Rijksmuseum. An intriguing portrait of a prominent figure of his time, I must say. Editor: The immediate feeling is one of measured authority, wouldn't you agree? His gaze is direct, almost penetrating. It gives you the sense of a person used to being listened to. Curator: Indeed. The portrait captures John Coutts, who was the Lord Provost, or Mayor, of Edinburgh. It reflects the increasing importance of civic leadership during the Enlightenment. Portraits like these cemented public perception of power and influence within local governance. Editor: That elaborate wig is a fantastic status symbol too. Not to mention the details in the coat buttons and fabric, each meticulously rendered. The clothing itself serves as an outward signifier of class, education, and good standing within his community. Are there hidden meanings there as well? Curator: It’s interesting to note the history of printmaking in the Netherlands as it democratized images. Engravings allowed portraits to be circulated more widely. McArdell skillfully reproduced Ramsay's original portrait for public consumption. It created a more accessible representation of civic authority. Editor: I'm thinking about the oval frame surrounding the subject. Isn’t that a familiar symbol from ancient Rome? The “imago clipeata,” it references a long line of ancestors—a distinguished past and an ambition for historical posterity. Curator: Absolutely. And look closely at the inscription. It’s not just a name; it's "Late Lord Provost of the City of Edinburgh," a deliberate act of remembering his role, securing his place in civic memory. It underscores how crucial public image was. Editor: I find myself dwelling on the contrast between the crisp details of his face and clothing and the slightly softer quality of the background. The engraver seems to invite us to consider his personal qualities against his civic functions. Curator: Which gets at how a portrait can be viewed as both an individual likeness and an expression of collective identity, serving to uphold or negotiate the dominant cultural narratives. It speaks to how we want to remember. Editor: I think, on second glance, it invites me to look more into the society, to discover the city this person served. Curator: And perhaps that is the role of a good portrait; a doorway into a richer understanding of the individual, his society and its values.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.