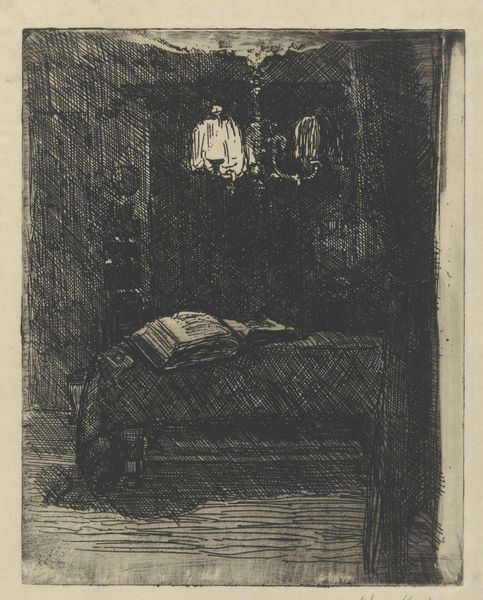

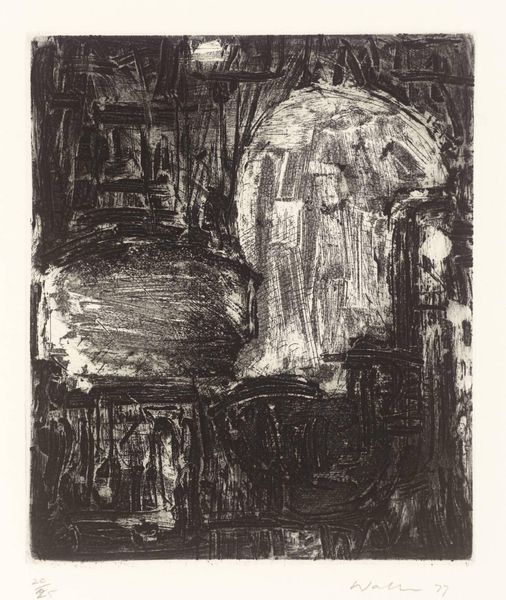

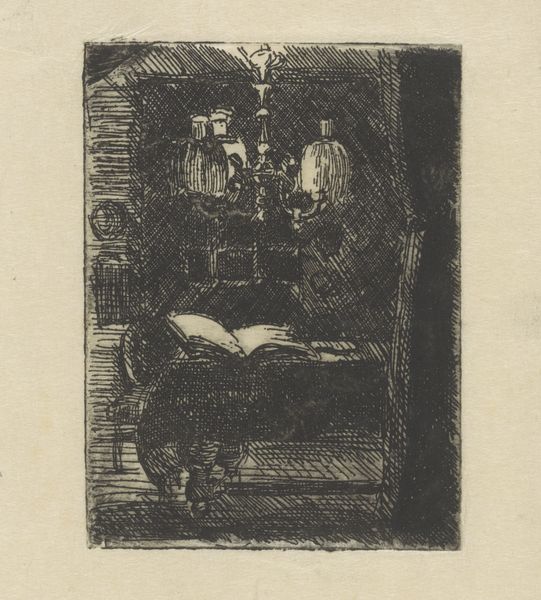

drawing, print, etching, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

etching

#

old engraving style

#

paper

#

ink

#

pen-ink sketch

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 240 mm, width 158 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This etching, "Interieur met spiegel en tafel met opengeslagen boek" or "Interior with mirror and table with open book", is attributed to Barbara Elisabeth van Houten and likely dates between 1877 and 1950. The work consists of ink on paper. Editor: It has this shadowy, almost haunting quality to it, doesn't it? The single light source highlights the furniture but leaves so much in darkness, like forgotten memories. Curator: The etching technique allows for the creation of fine lines and subtle tonal variations, capturing the details of the interior and its furnishings. It gives the composition a tangible atmosphere. Notice how the mirror and chandelier feature so prominently, offering glimpses into the societal importance of domestic space in this era. Editor: I agree, it's fascinating how domestic space, especially in art by women artists, became a site to challenge gender roles and expectations. An open book and prominent writing desk may point towards woman and intellectual labor in a private setting, reclaiming narratives of their own. The room, as rendered in the work, seems so solitary and serene but I am intrigued by its occupant, or lack thereof. Curator: It does leave you pondering who might have been reading at that table, doesn't it? It captures a slice of bourgeois life during that period and reflects societal values in a very intimate way. The presence of furniture as an important element helps illustrate class and taste as indicators of privilege. Editor: Absolutely. And the "realism" tag becomes significant because the rendering is accurate and intimate, without overt romanticism or idealization. The very act of truthfully depicting a woman’s personal space is indeed a challenge, subtly questioning conventional societal portrayals. It asks what is obscured and made invisible within this interior world? Curator: Van Houten seems less invested in high academic painting and focuses more on realistic glimpses into ordinary lives, capturing intimate views with skill. This gives rise to fascinating social commentary. Editor: This is exactly why art history remains valuable. Situating even unassuming art works like this print can yield so much information and contribute a new level of appreciation of the role of women as not just observers but vital producers of culture. Curator: Precisely. This quiet scene resonates beyond its visual elements, encouraging conversations around gender, class and representation in 19th-century artistic circles.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.