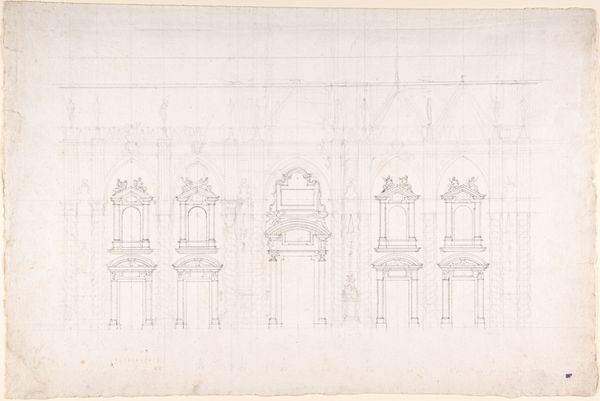

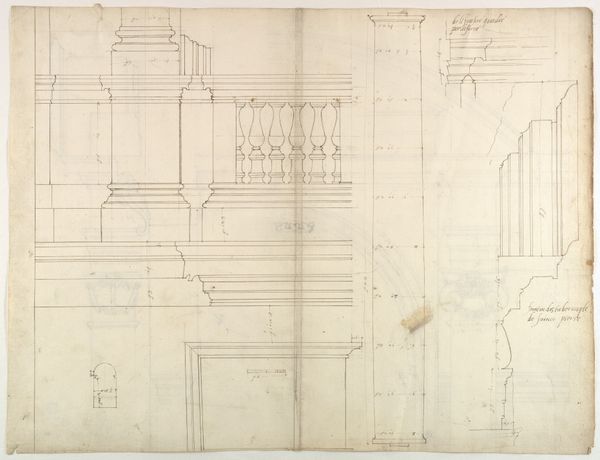

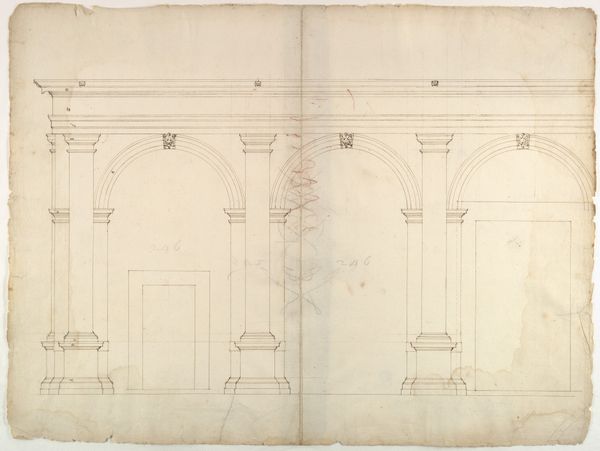

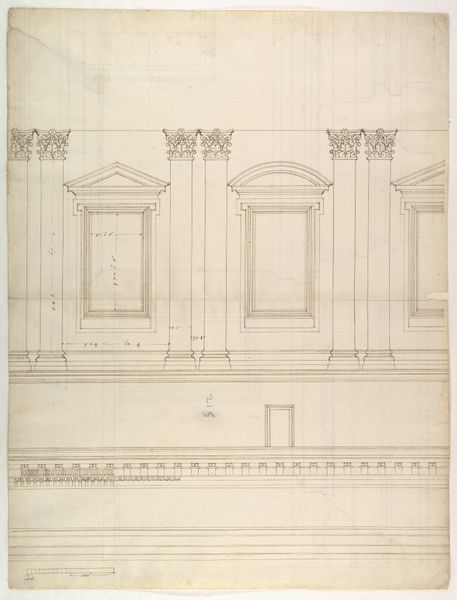

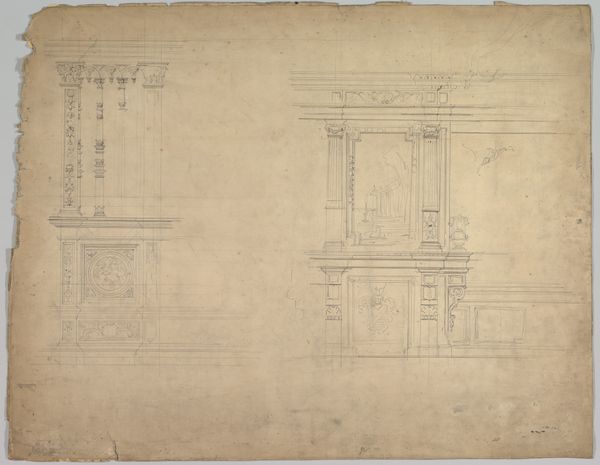

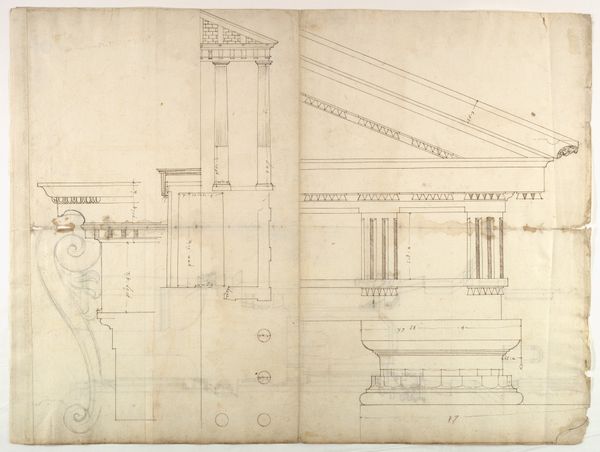

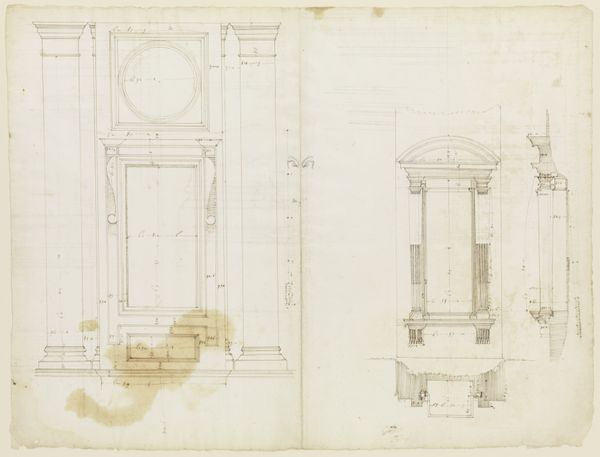

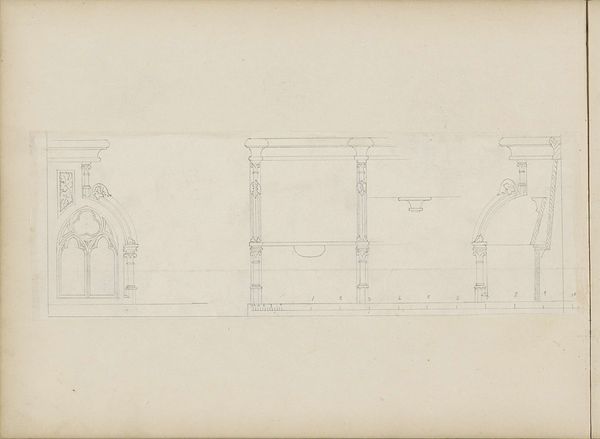

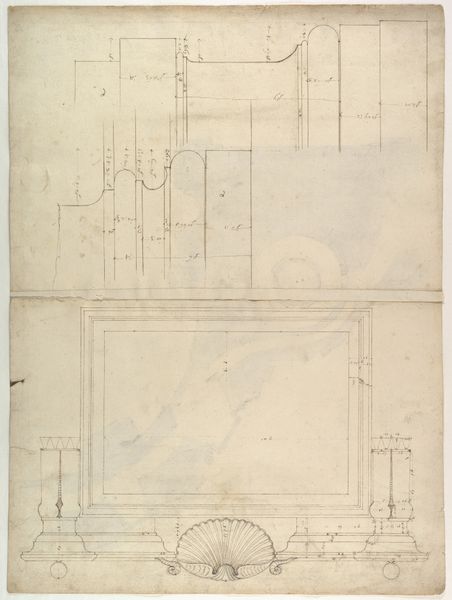

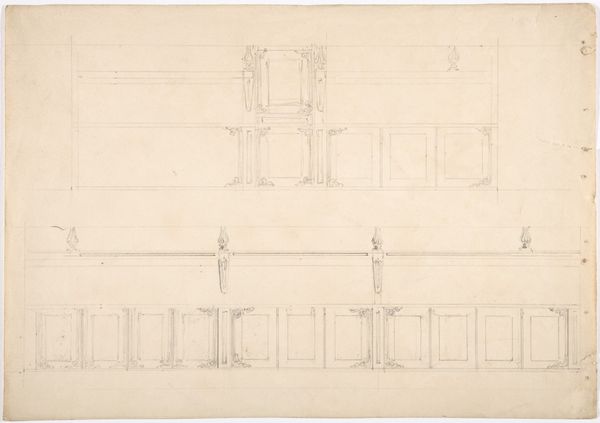

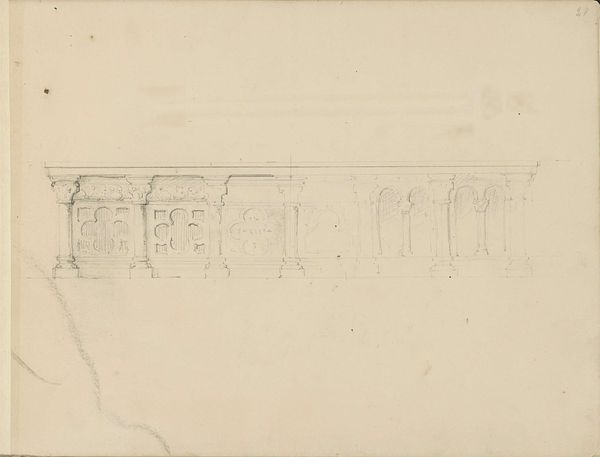

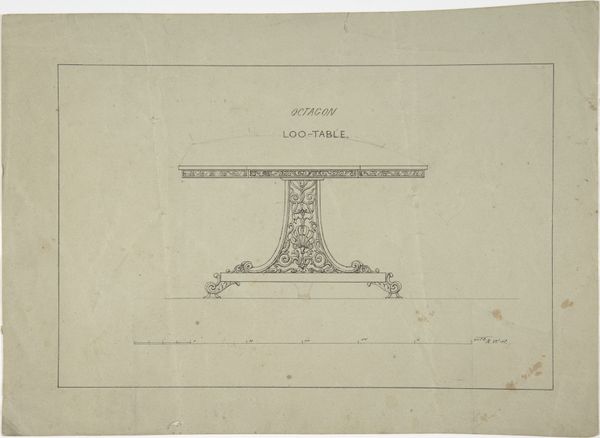

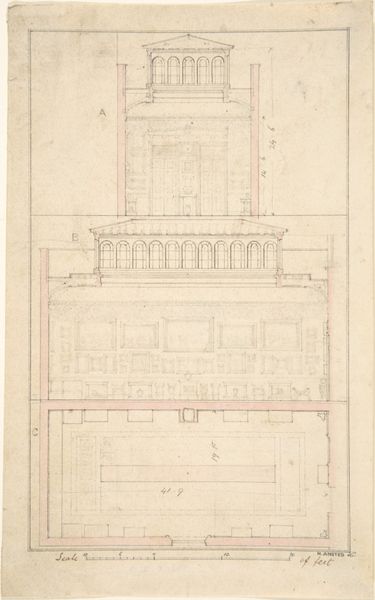

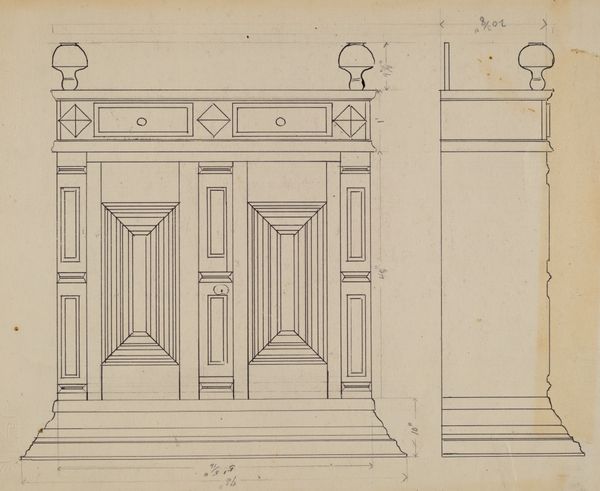

Design for an Obelisk; Partial Design in Elevation for Colonnade in the Doric or Tuscan Order (recto); Design for Fluted Column on Podium in Elevation (verso) 18th century

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, paper, pencil, architecture

#

drawing

# print

#

classical-realism

#

paper

#

form

#

geometric

#

column

#

pencil

#

line

#

architecture

Dimensions: 16 5/8 x 11 1/4 in. (42.2 x 28.6 cm) (irregular borders)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have "Design for an Obelisk; Partial Design in Elevation for Colonnade in the Doric or Tuscan Order (recto); Design for Fluted Column on Podium in Elevation (verso)," an intriguing 18th-century drawing now residing at The Met. It appears to be pencil on paper. Editor: It looks incomplete, a ghostly whisper of architectural ambition. Almost fragile, really. What purpose did it serve, do you think? Curator: Architectural drawings like these were crucial tools for design development and communication. Draftsmen meticulously rendered these designs, often combining multiple concepts onto a single sheet as we see here, probably as preliminary explorations for larger projects. It's a window into the world of building. The material itself speaks to a moment of transition. Editor: The precision is striking. What materials were commonly used for actual construction at the time that these sketches are from? Was there a move toward more durable substances to align with the designs? Curator: The 18th century saw widespread use of materials like brick, stone, and timber, varying by region, availability, and cost. The social implication of the project also plays a factor. These materials represent societal values tied to the function of the building, and thus are reflective of power dynamics. Drawings were relatively inexpensive while still effectively communicated plans to investors. Editor: Interesting. I'm thinking about the intended audience, and how these drawings translate into real-world structures. Who would have seen this? Were they for public consumption, or just within the architect's workshop? Curator: Most likely, drawings like these would have been circulated within architectural circles, presented to patrons for approval, and used as guides by craftsmen on site. Its audience likely dictated its degree of finish. Drawings that needed investors would look far different than ones used in-house by the designer. Editor: Thinking about its role, it emphasizes the political function architecture served during this era. Public structures were inherently charged with significance, shaping the landscape in tangible ways to align with ideology. Curator: Exactly. The design echoes of the classical, Roman-Greco forms that would dominate much Western civic spaces, evoking an idea of eternal structures representing an established rule. But what strikes me most is the intimacy of a sketch – to see the origin of something grand. Editor: I see what you mean, seeing these geometric lines rendered with such care really puts the creation of cities into perspective, thinking of the skilled workers involved. The material realities make me really appreciate all this effort and planning involved in architecture. Curator: Precisely. The object and history can truly inform one another. Editor: Indeed. Well, thanks for your insight! Curator: My pleasure.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.