Saperlotte!... que je voudrais... que ma femme ait fini... 1844

0:00

0:00

drawing, lithograph, print, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

lithograph

# print

#

caricature

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

pencil

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

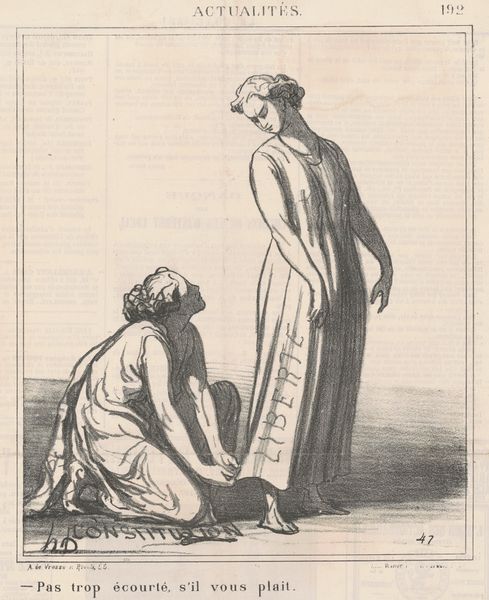

Curator: What strikes me immediately is the stark contrast in energy and expression. Editor: Indeed. We're looking at Honoré Daumier's lithograph from 1844, titled "Saperlotte!... que je voudrais... que ma femme ait fini..." or "Damn it!... How I wish... my wife would finish..." in English. It's a piece rife with social commentary, even now. Curator: Absolutely. You have a sense of the man rushing, hunched over, weighed down maybe by expectations. And then the wife stands serenely, or perhaps obliviously, reading, bathed in what seems like calm light. The implied labor on one side and leisure on the other jumps out at you. Editor: Consider Daumier’s use of lithography itself here. A relatively accessible printmaking technique for the time, it allowed his social critique to reach a wider audience. This work and its caption place a domestic pressure – a wife taking her time reading while her husband anticipates or provides, maybe through financial toil. Curator: The male figure almost seems comical in his harried state and his clothing, while the female figure embodies that rigid, ideal beauty of the era. The work critiques the socially constructed roles, right? Highlighting the disparity in how labor and leisure were distributed, specifically along gender lines. Editor: I'd add how Daumier contrasts the texture to make that distinction sharper: his hurried lines render the man, with tight, crosshatched lines suggesting the anxiety etched in the lines of his figure and garment; conversely, her form is flowing, rounded. Curator: Right! She's static, smoothed and highlighted—maybe even unaware or uncaring of the contrast that is literally created on this sheet of paper. What's interesting is thinking about how this domestic tension is not locked in time. Editor: These images of societal frictions, captured through accessible materials, were intended to reach an audience and inspire conversations – a role I still believe art must perform. It uses these class and gender dynamics we're discussing as a material – not unlike ink – for building the overall picture. Curator: Yes. Ultimately it serves as a visual tool that encourages us to question entrenched power structures and expectations, while understanding the impact on the labor force across race, class and gender. Editor: This work makes clear the important work that lies in making as it does viewing—asking those tough questions, even if the ink is only grayscale.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.