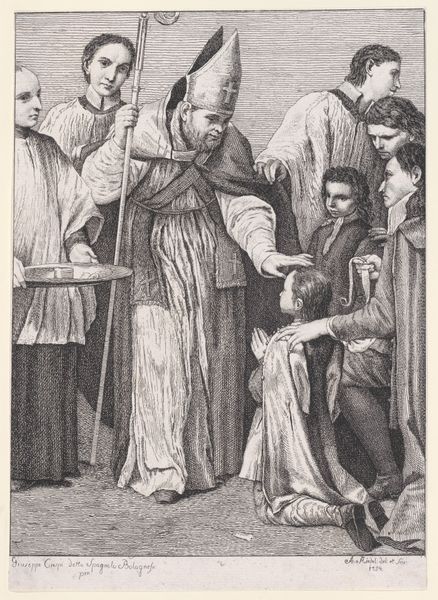

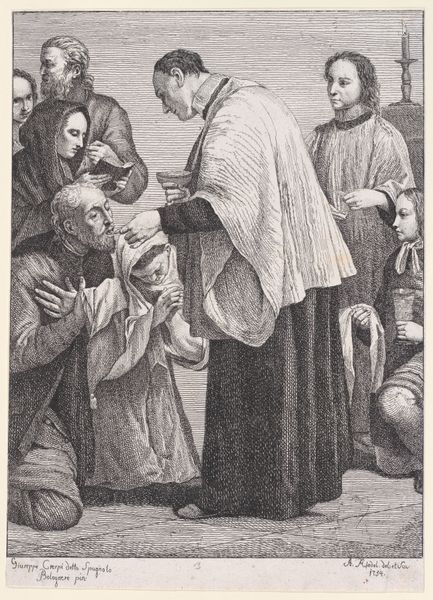

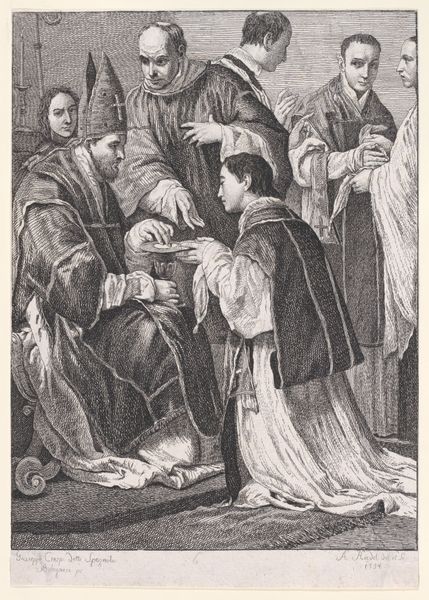

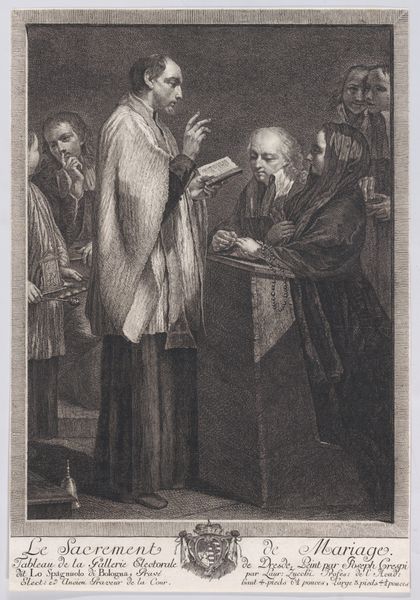

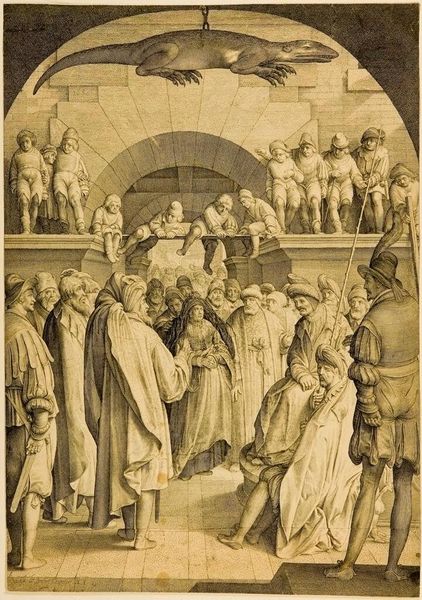

St. Ambrose, Archbishop of Milan, Turning Back Emperor Theodosius 1681

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

men

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: sheet: 17 x 11 11/16 in. (43.2 x 29.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is Claude Mellan’s "St. Ambrose, Archbishop of Milan, Turning Back Emperor Theodosius," from 1681. It's an engraving. The figures look like they're made of fine lines. What do you see in how Mellan rendered this confrontation? Curator: Considering this work through a materialist lens, it's compelling to look at the labour involved in creating such a detailed engraving. Imagine the artist, meticulously working line by line on the metal plate, reproducing a narrative loaded with political and religious meaning. The starkness of the medium itself highlights the power dynamic – who commissions this work, and for what purpose? Is it a celebration of religious authority or a commentary on temporal power? Editor: That makes sense. So, you are thinking about who had the means to produce and distribute it, not only Mellan's technique? Curator: Precisely. How was this print intended to circulate? Think of the consumption of religious imagery in 17th-century Europe and the potential role of prints in shaping popular opinion. The "means of production" aren't just about Mellan's skill with the burin, but about the entire economic and social network that supports and enables his work. What message was the church selling here, to those who were buying the art? Editor: So, it is interesting to think of who commissioned such art piece. Maybe that could tell us something more about the conflict, and maybe where the artist sympathies lay... Thank you for giving me a broader idea of prints as material. Curator: Indeed, considering art not just as an image, but as a material product embedded in a complex web of power, labor, and consumption, unveils new ways of appreciating "St. Ambrose."

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.