daguerreotype, photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

united-states

#

albumen-print

#

realism

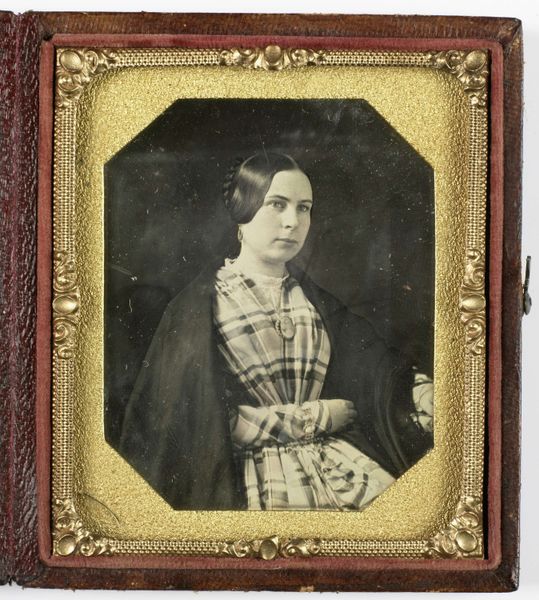

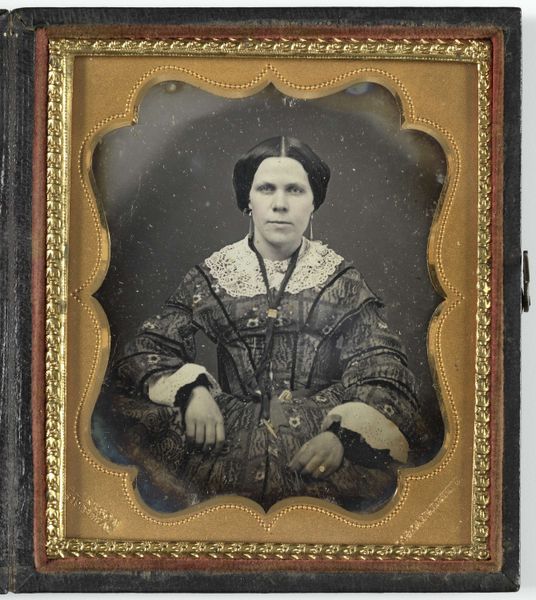

Dimensions: 10.7 × 8.3 cm (4 1/4 × 3 1/4 in., plate); 12 × 21.2 × 1.2 cm (open case); 12 × 9.9 × 1.9 cm (case)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: We’re looking at “Untitled (Portrait of a Seated Woman),” a daguerreotype from 1858 by Otis Hubbard Cooley, residing at The Art Institute of Chicago. I'm struck by the formality of this image, and its preservation in this ornate case. What aspects of this piece capture your attention? Curator: Daguerreotypes were, for a brief period, the dominant mode of photographic portraiture. Consider this: who had access to portraiture before photography? Predominantly the wealthy. Daguerreotypes democratized portraiture to an extent, making it accessible to a growing middle class. But look closer; is this democratization truly egalitarian? Editor: I see your point. Even though photography made portraiture more available, the expense involved would still make it beyond the reach of some. Curator: Exactly. Consider the setting, the subject's attire, and that elaborate shawl. Photography was rapidly evolving, but portraiture remained firmly rooted in the established social order. It reflects both technological advancement *and* enduring class structures. The studio backdrop, though simple, hints at an aspiration for elevated social standing. Does the woman’s direct gaze engage you or challenge you, do you think? Editor: It feels a little challenging. There's an attempt at conveying respectability, but also, maybe, a hint of unease? Like she's not entirely comfortable with the performance. Curator: Precisely. That tension makes the photograph so compelling. It's a record, yes, but also a constructed image laden with social and cultural meaning. We are not simply looking at a lady. What is she telling us about how she wants to be seen? About who got to control that seeing? Editor: That's fascinating. I’ll definitely be thinking more about that tension and control going forward. Thanks for pointing it out. Curator: It’s a crucial point when considering portraiture of this era; something I’m happy to see you now recognizing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.