daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

framed image

#

united-states

#

realism

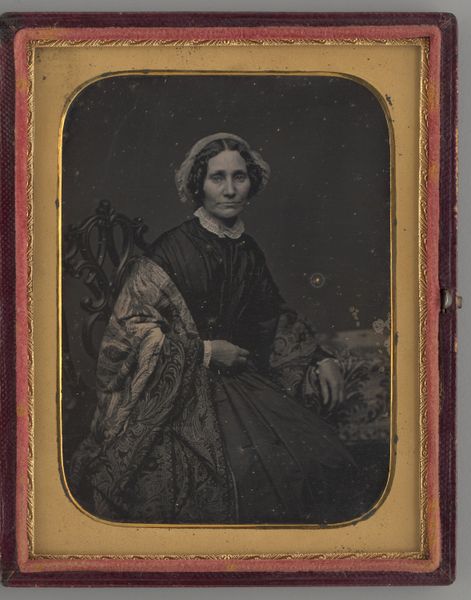

Dimensions: 10.7 × 8.3 cm (4 1/4 × 3 1/4 in., plate); 11.9 × 18.6 × 1.2 cm (open case); 11.9 × 9.3 × 2 cm (case)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have an untitled portrait of a woman dating back to 1853, currently residing here at the Art Institute of Chicago. It’s an early example of photography, specifically a daguerreotype. Editor: The stark contrast and limited tonal range immediately strike me. It's an almost severe composition, relying heavily on light and shadow to define form. There is also something haunting about her gaze. Curator: Absolutely. The daguerreotype process itself contributed to that effect. It required long exposure times, resulting in a still, almost frozen image. What strikes me is how this kind of portrait democratized image making. Finally, the middle class had some access to representation! No more portraits strictly for the aristocracy! Editor: I see your point, but even within these constraints, consider how the light drapes across her shawl and the way her dark dress absorbs the illumination, drawing our eye inevitably toward her face. The soft focus enhances the delicate nature of her features. I also note the careful arrangement of props – the table, the basket, perhaps hinting at her domestic role? Curator: Indeed! These photographs became potent symbols of identity and status within a rapidly changing society. What’s fascinating is that even without knowing her name, we can speculate about her socio-economic position. Her attire, while simple, speaks of modest affluence, a signifier of a specific class aspiration of that era. These portraits became statements, announcing one's presence in the social sphere. Editor: Precisely. And look closely—the frame itself. The framing is part of the piece; it serves to isolate and elevate her. The ornamental frame transforms a simple portrait into a treasured object, something to be displayed and admired. But its elaborate nature does feel somewhat incongruous with the woman’s modest mien. Curator: Perhaps a reflection of the aspirational qualities you observe in these new kinds of portraits and photographs? The democratization of representation doesn't equate to an end to aestheticizing practices, no? Editor: Fair enough! After our close examination of the composition and light, I find myself appreciating the picture’s simple strength. Curator: And for me, the power in understanding photography’s capacity for change and societal identity continues to offer rich insight.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.