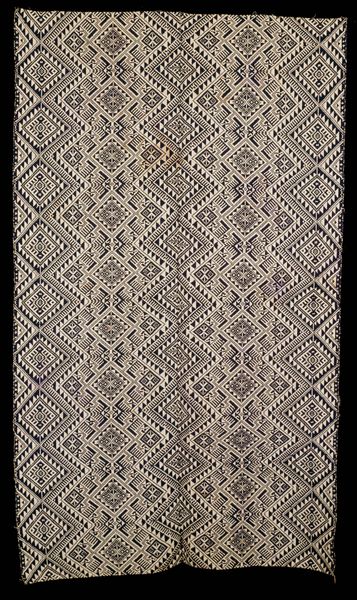

weaving, textile

#

weaving

#

textile

#

geometric pattern

#

geometric

#

intricate pattern

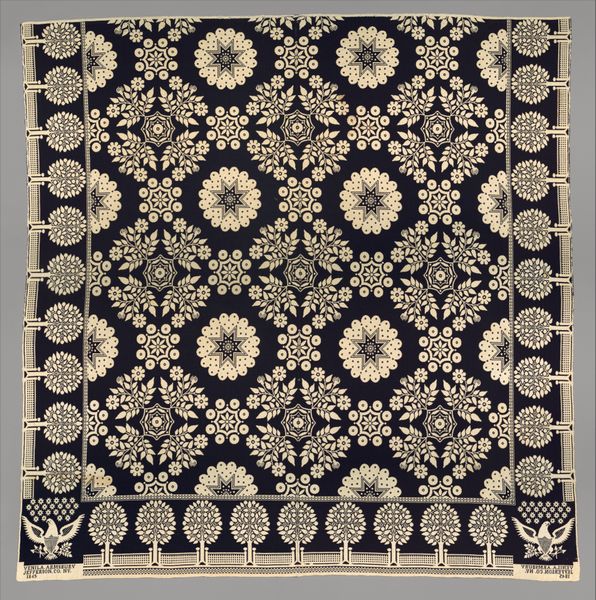

Dimensions: 229.9 × 198.3 cm (90 1/2 × 78 1/4 in.) Repeat: 48.1 × 48.1 cm (18 7/8 × 16 3/8 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

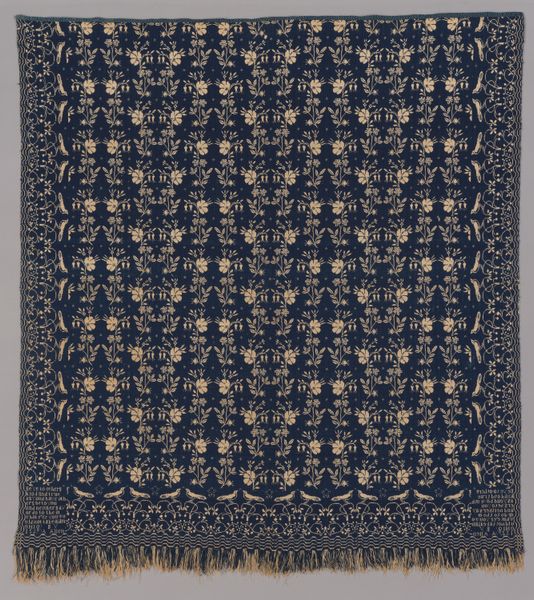

Curator: This exquisite textile, titled "Coverlet," was crafted in 1851 in the United States. Its attributed creator is James McDougal Hart. The medium consists of wool, weaving, and print techniques, a testament to the period's artisanal practices. Editor: My immediate reaction is drawn to the coverlet's intense visual complexity. The stark contrast between the deep navy background and the intricate, almost lace-like white patterns is immediately striking. It creates a captivating visual rhythm. Curator: Precisely! Let's consider this intricate pattern's social context. During this period, coverlets like these served not just as bed coverings but also as displays of skill and prosperity. The process involved considerable labor and technical expertise in both weaving and potentially early print techniques. The availability of wool and dyes would also reflect the maker's access to resources. Editor: Looking at the pattern itself, there's a fascinating tension between symmetry and organic form. The repeated motifs—floral arrangements, urns, and what appear to be stylized birds—create a clear, structured grid. However, within each motif, there's a remarkable amount of detail, preventing the overall design from feeling static or overly rigid. Curator: Absolutely, this pushes against the boundaries between art and craft, raising questions about who created such pieces and for what purpose. Were these individuals viewed as skilled artisans, or did they possess artistic sensibilities comparable to more celebrated artists? It forces us to reconsider how labor and materials contribute to cultural narratives. Editor: The repeating bird and floral motifs almost have a symbolic effect through their systematic deployment, imbuing them with heightened attention. Are the motifs pointing towards any particular belief system in mid-19th century United States, maybe a romantic view of nature or something about society at the time? The materiality certainly adds richness and dimension to it. Curator: Good point. These weren’t mass-produced. This involved a conscious aesthetic choice from the laborers as the product’s very nature speaks to localized economics and social structures—perhaps even the dynamics of trade networks connected to wool production and dying. The fact that it survived in good condition raises other materialist questions too regarding curation of this labor and these resources. Editor: Considering the symmetry, contrast, detail, and texture really highlights how such careful choices create something captivating that could almost represent time standing still. We are fortunate this coverlet made its way to the Art Institute of Chicago so we can admire these patterns and techniques so many years later. Curator: I concur. Investigating the object of production illuminates aspects regarding cultural worth and communal creativity. A compelling case about a period item beyond just aesthetic values.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.