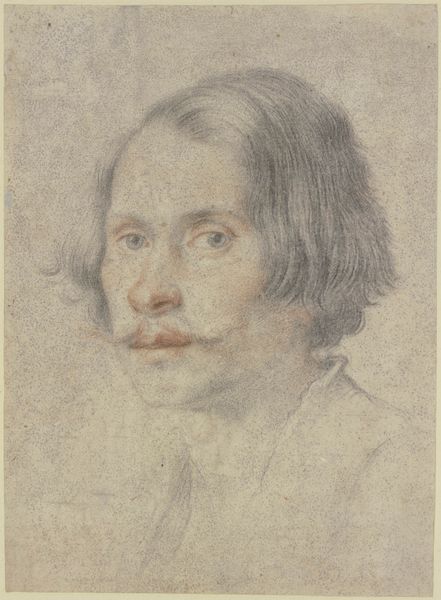

drawing, gouache, chalk, charcoal

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

gouache

#

charcoal drawing

#

chalk

#

charcoal

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have a striking portrait, "Brustbild eines Mannes mit Schnurr- und Kinnbart" by Jacob Jordaens, currently housed in the Städel Museum. It's a study rendered in charcoal, chalk, and gouache. What is your first reaction to it? Editor: There’s an immediate vulnerability here. The man’s gaze meets ours, but it’s also slightly averted, as though he’s aware of being observed, weighed, and judged, really encapsulating some heavy power dynamics. Curator: Absolutely, and consider the context in which such a portrait was created, even if this wasn't a finished commission but more of a study. The meticulous attention to detail—particularly in the hair and facial hair—speaks to the growing importance of the individual, particularly bourgeois men in society at that time. Editor: It also reads as very deliberately constructed masculinity. He’s framed in a rather conventional way: sturdy neck, controlled beard and moustache, all of it aligning him with existing ideas of the stable, self-possessed patriarch, while that gaze holds it all just barely in check. Curator: Exactly. Think about the evolution of portraiture, especially in the Baroque era, and the symbolic load they often bear. What’s omitted is as vital as what’s included. By choosing a bust-length portrait, for example, Jordaens emphasizes intellectual and spiritual depth rather than social status—although one could argue social status is absolutely inherent to even the notion of having your portrait done. Editor: And even that feels carefully negotiated; I mean, given the materials and the relatively understated attire, I'm struck by the question of accessibility, in terms of production and reception. If he had used oils or more luxurious items it would clearly denote a specific patronage and class association, right? As is, the intimacy comes across without these heavy material markers. Curator: That's an astute observation. Jordaens, though working within the Baroque style, offers a more human portrayal. It doesn't deify or elevate like a Rubens might have done. It's a window into the everyday of a specific segment of society. It doesn’t lean on readily accessible conventional cues to denote social meaning—leaving us to wrestle with the expression on his face, his subtly shifting gaze, and the implied narrative. Editor: Thinking about how Baroque portraiture functioned within a larger context of burgeoning capitalist expansion really frames how carefully his gaze invites participation. As such, I wonder about the broader implications of images like this today, in an age of omnipresent self-documentation? What, if anything, does the cultural memory in them invite from our viewership, outside of just some stuffy admiration? Curator: An excellent question, it compels us to continuously re-evaluate our connection with both past and present. Editor: It absolutely does; for me, art isn't about what something simply "means", but what it might be *for*. Thanks for unpacking this piece with me!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.