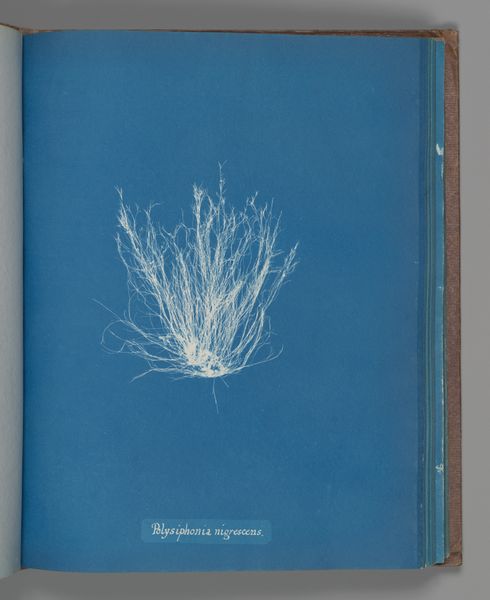

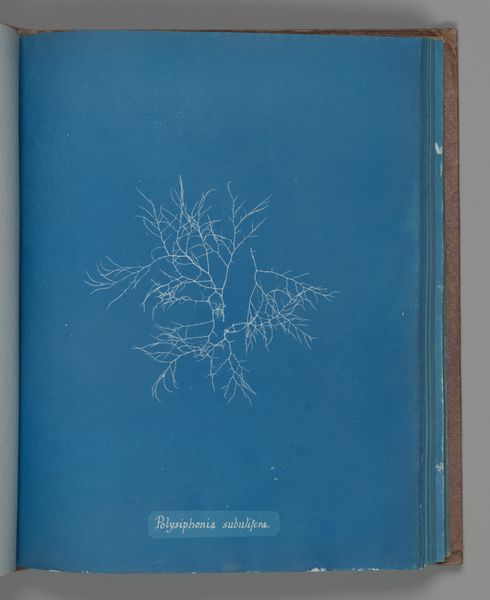

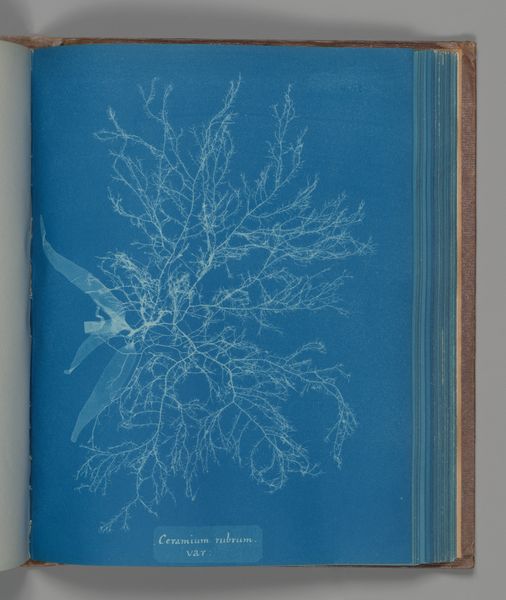

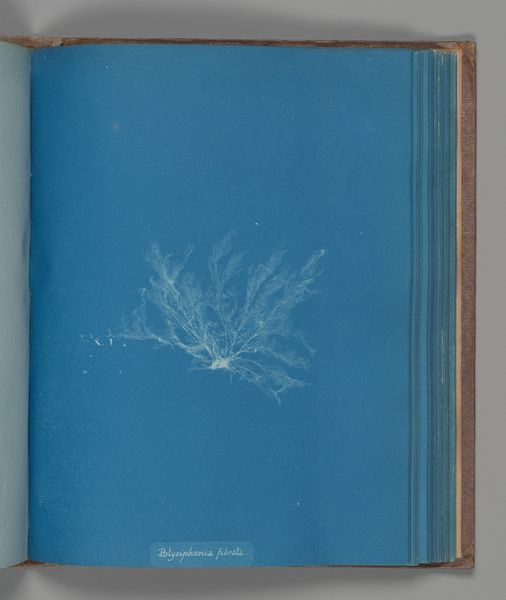

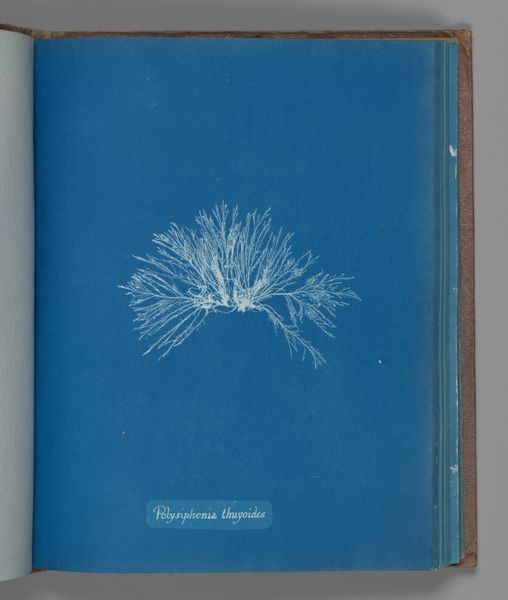

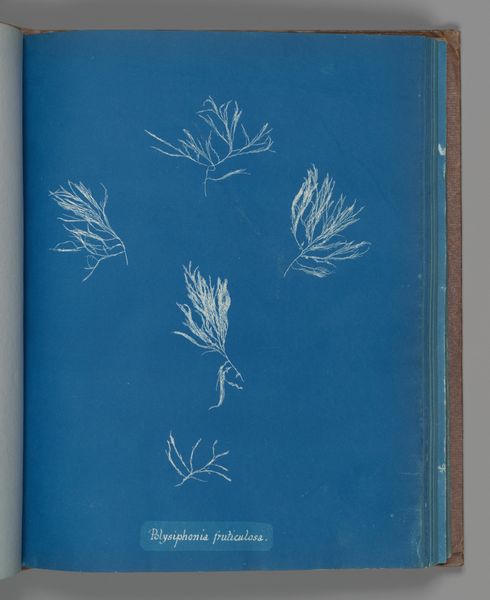

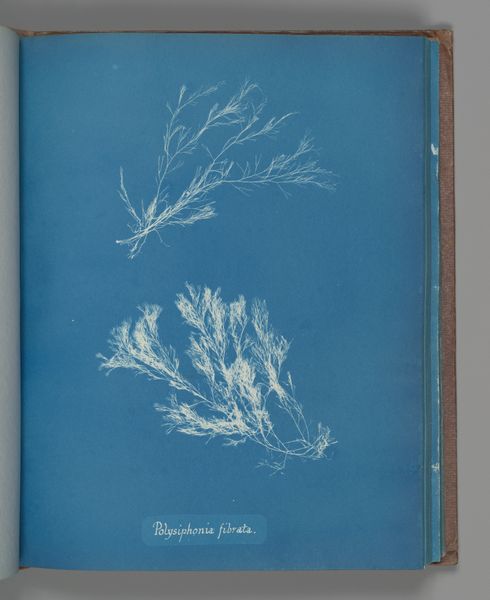

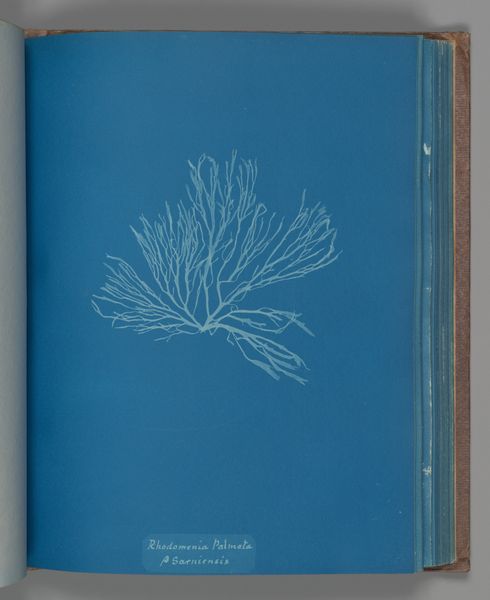

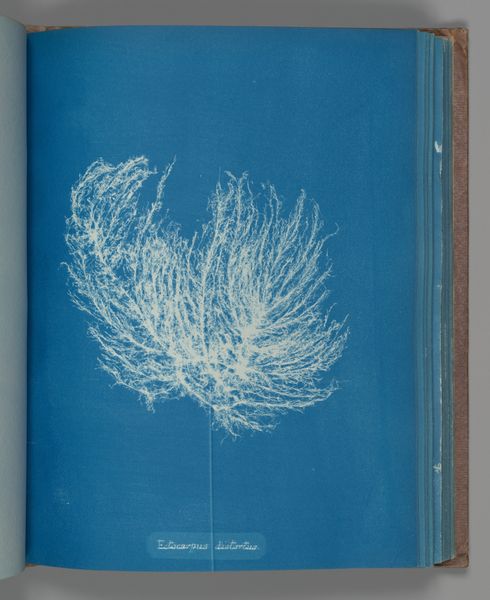

print, paper, cyanotype, photography

#

still-life-photography

# print

#

paper

#

cyanotype

#

photography

#

plant

#

naturalism

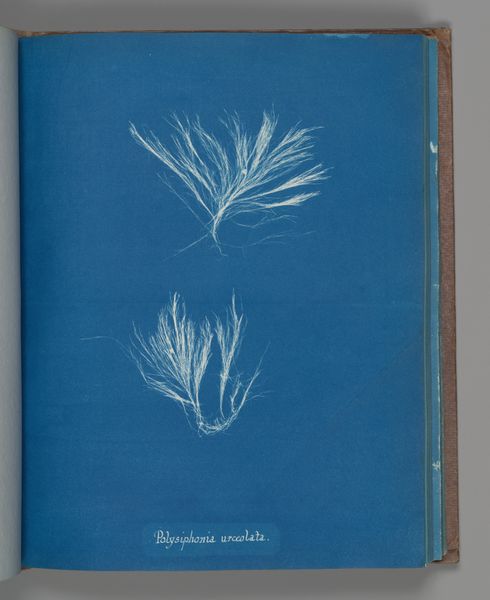

Dimensions: Image: 25.3 x 20 cm (9 15/16 x 7 7/8 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Looking at this remarkable piece, we are observing a cyanotype from the hand of Anna Atkins, titled "Polysiphonia byssoides", dating from somewhere between 1851 and 1855. Editor: It is startling in its simplicity! The stark white tendrils against that vibrant Prussian blue ground evokes a powerful sense of spectral presence and ethereal otherworldliness. Curator: Indeed! And the choice of cyanotype – a photographic printing process using iron salts – is no accident. Atkins was not just an artist but a botanist, documenting algae specimens with scientific precision. As such, the image represents more than art, becoming a record of knowledge dissemination during the Victorian era where scientific thought saw explosive growth. Editor: It calls to mind older botanical illustrations, which similarly tried to freeze organic forms in a static pose. But that vivid blue has a transformative impact; rather than seeming pinned and lifeless like specimens in herbaria, the plant possesses a haunting presence, one that echoes the spiritualist sentiments of the Victorian period. What do you make of the symbolic choice of seaweed, something that straddles land and the mysteries of the water, that unknown frontier? Curator: It’s compelling because it pushes against established gendered roles, and her art is inextricable from this discourse! Consider that even as women like Atkins were making substantial contributions to science, they often lacked the institutional support and recognition afforded to men. Atkins leveraged the accessibility of photography as an alternative medium through which women such as her might gain traction in intellectual fields otherwise inaccessible to her. Editor: True! And even the cyanotype process itself mirrors alchemical symbolism, doesn’t it? Blue, the color of knowledge, of the heavens, captured through a process that feels almost magically reproducible. One wonders how early viewers experienced this piece given this tension between scientific record and perceived enchantment! Curator: It asks us to confront uncomfortable questions about art history! Where and how do we choose to include such figures, and under what lens are they to be appreciated? Hopefully, continued scholarship and recognition will give us more clarity! Editor: What better way to end a viewing experience by being led toward seeking yet more ways to look, perceive, and contextualize such powerful artwork!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.