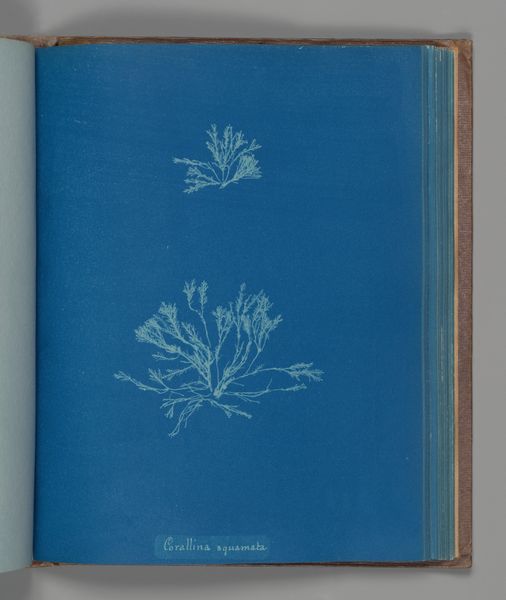

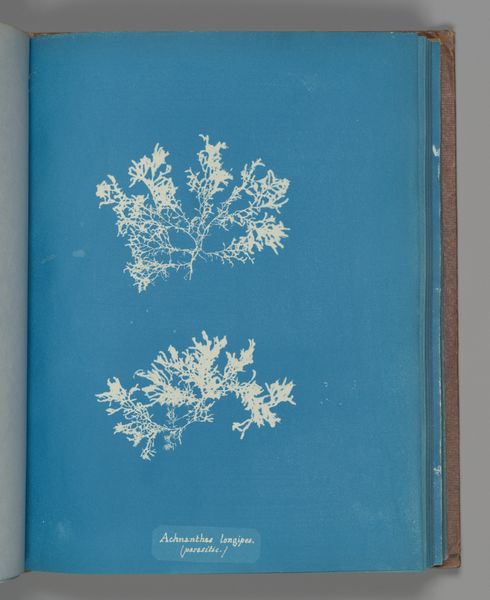

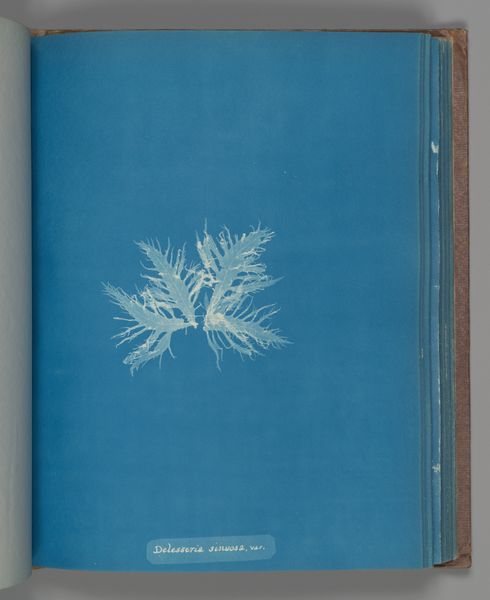

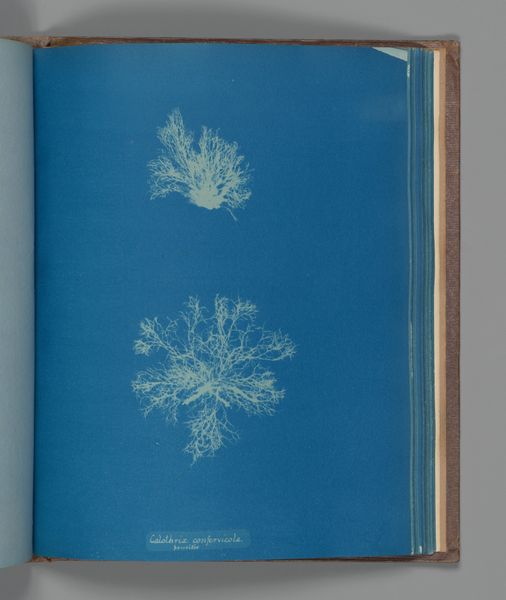

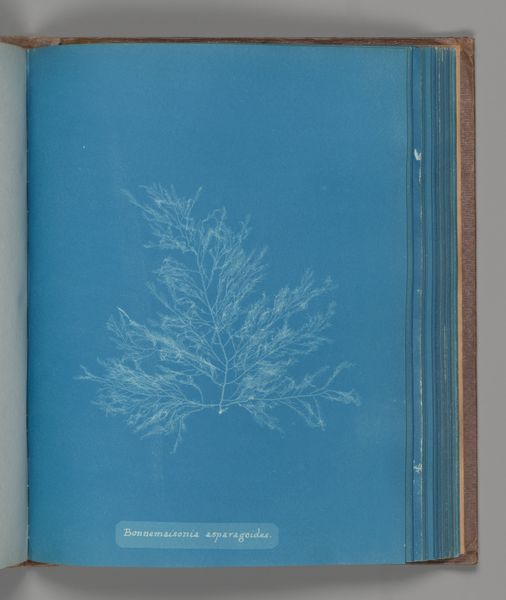

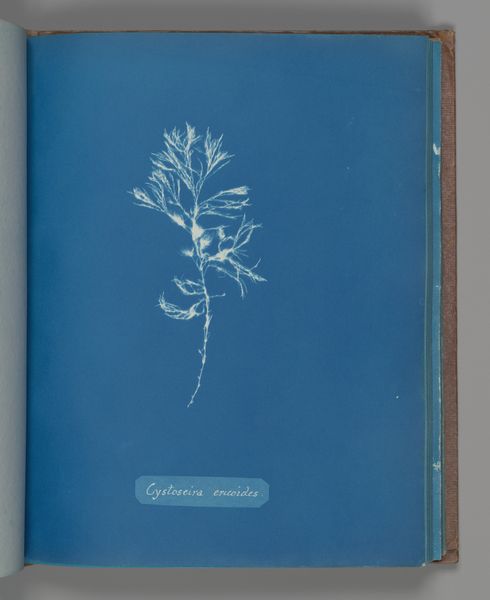

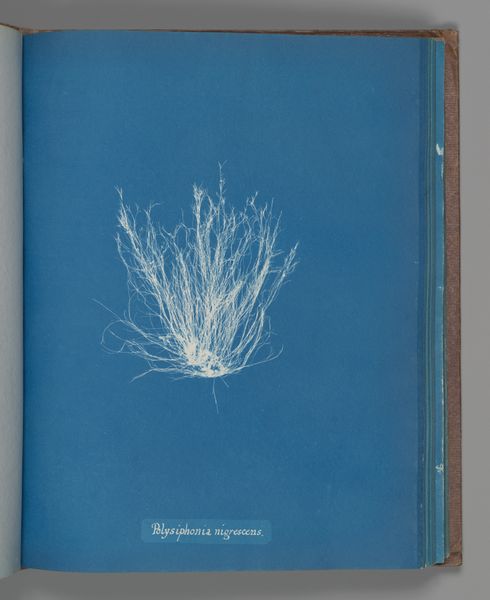

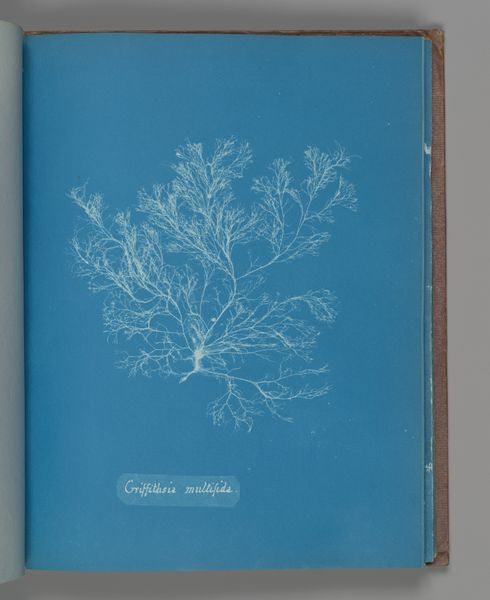

print, paper, cyanotype, photography

#

still-life-photography

# print

#

paper

#

cyanotype

#

photography

#

realism

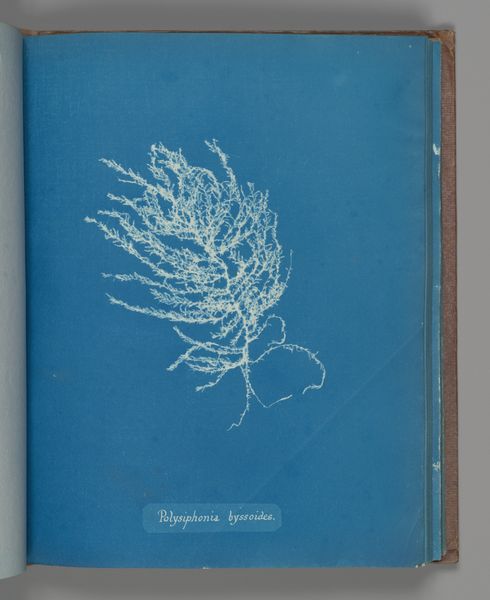

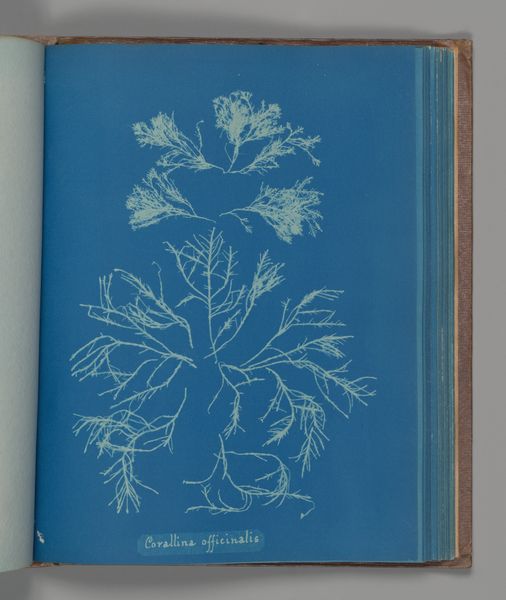

Dimensions: Image: 25.3 x 20 cm (9 15/16 x 7 7/8 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

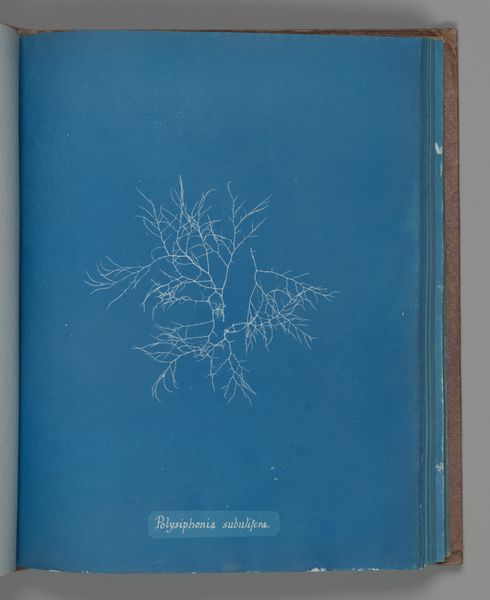

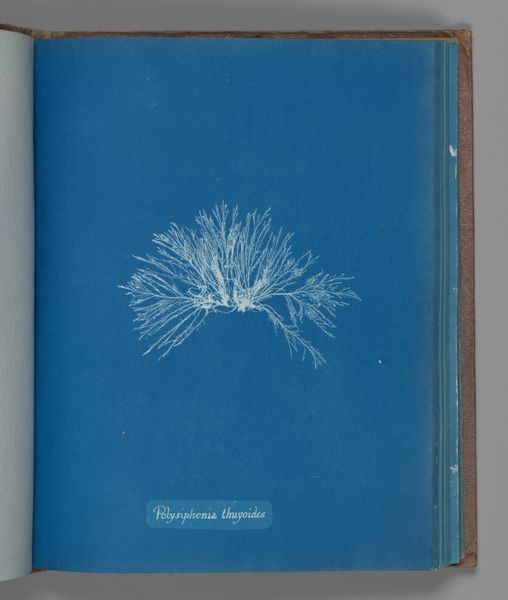

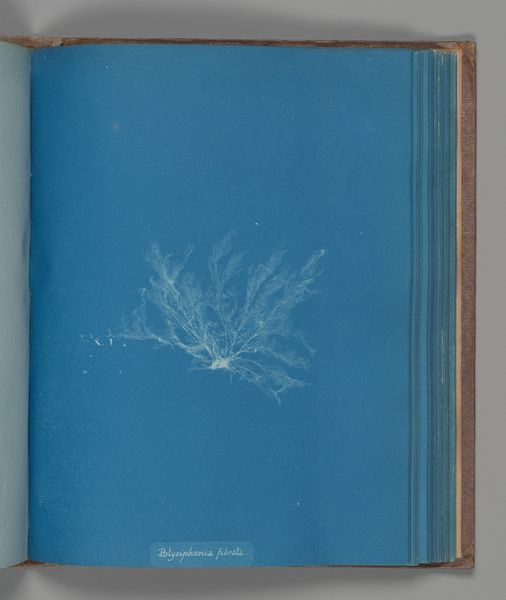

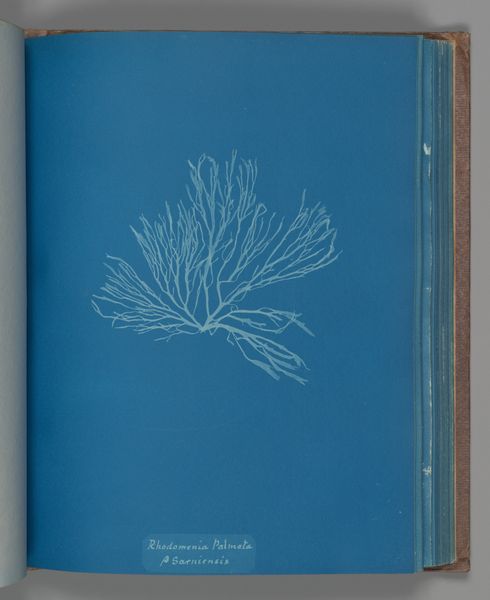

Curator: Looking at this exquisite print, one might easily mistake it for a carefully rendered drawing. However, it's actually a cyanotype photograph of Polysiphonia cristata, a type of red algae. The artist is Anna Atkins, and it dates between 1851 and 1855. Editor: My first impression is of a ghostly botanical print, simultaneously delicate and assertive. The stark white against that rich Prussian blue evokes something ancient, like an imprint from a lost world. Curator: Precisely. Atkins was a botanist as much as she was a photographer. This work, created not long after photography's invention, blurs the lines between scientific documentation and artistic expression. It speaks volumes about the Victorian era’s fascination with natural history, but also, her dedication challenges prevailing ideas around female capabilities and public roles. Editor: The blue is just incredible! Blue is associated with loyalty, intelligence, and sadness, but also openness to the world and new findings. You know, seaweed and marine life often symbolize adaptability and the mysteries of the subconscious. I can't help thinking how powerful is to see a woman portraying this symbol with that very peculiar cyanotype. Curator: Her pioneering work also influenced the accessibility of scientific knowledge; cyanotypes allowed for mass production, at a time when printed books were more limited. Anna Atkins democratized access to botanical specimens that few could observe firsthand. It really challenges assumptions about photography as a purely artistic medium. Editor: A visual anchor! It's quite incredible. Something we may see simply as a pretty print has a symbolic and historical significance. It prompts reflections on women and their place in Victorian society, but, also, it subtly connects us with nature's ever-changing, resilient character. Curator: It demonstrates the interwoven relationship of art and science—that’s very true. Thinking about the institutions, Atkins's cyanotypes became examples for her male peers—the democratization you pointed out! These prints weren't made to hang on gallery walls but rather to be consulted like books. They circulated as crucial forms of visual information. Editor: It does go to show how our perception and reception of artworks constantly evolve. Who would think such scientific imagery would, more than 150 years later, be displayed in The Met, carrying meanings perhaps Anna Atkins herself would never foresee!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.