print, woodcut

#

narrative-art

# print

#

figuration

#

woodcut

#

northern-renaissance

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

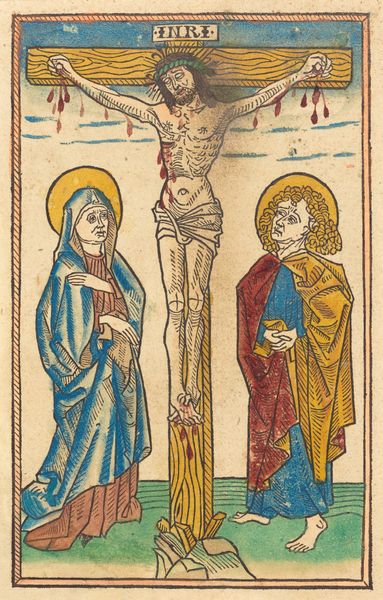

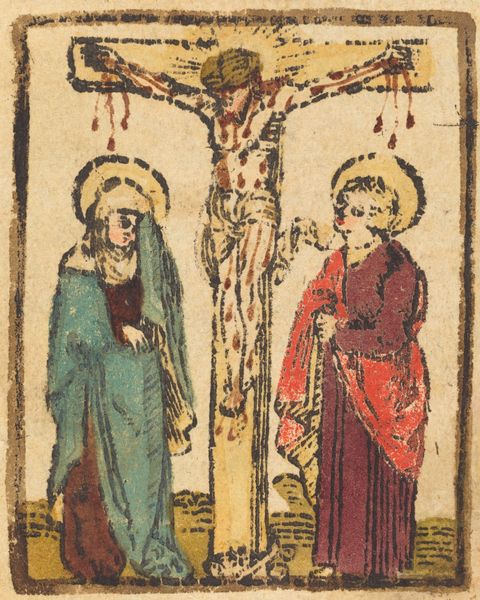

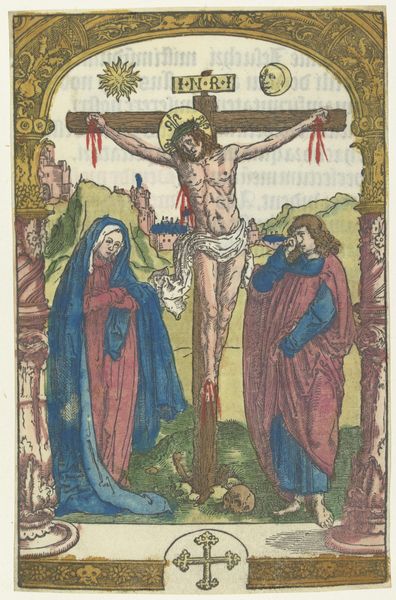

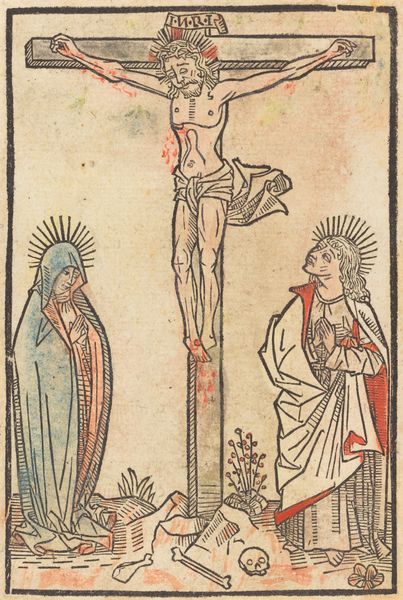

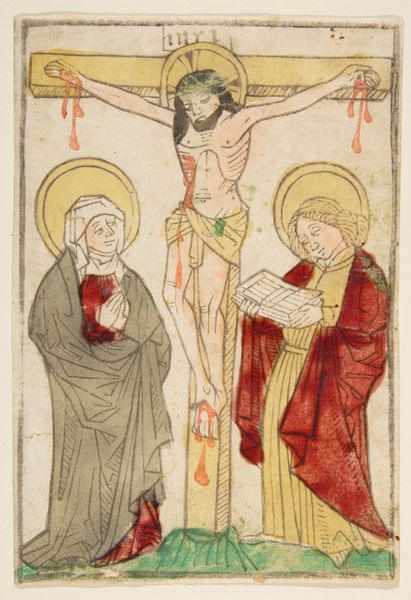

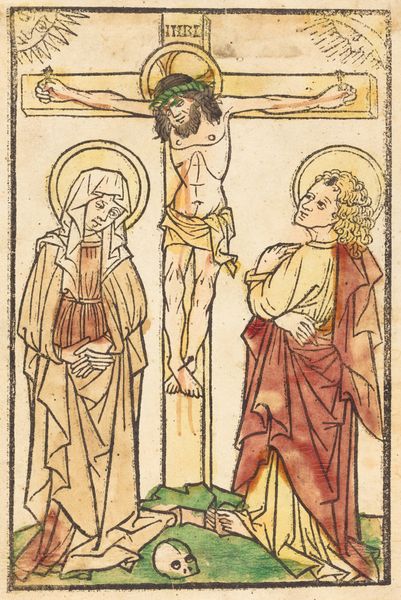

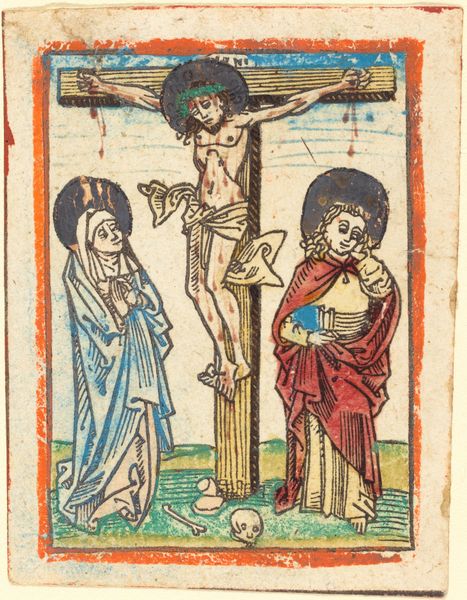

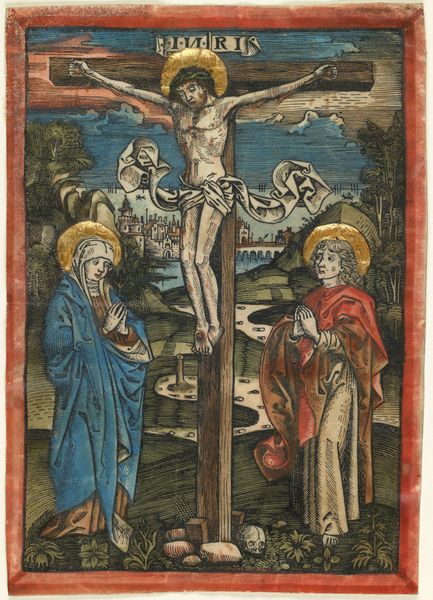

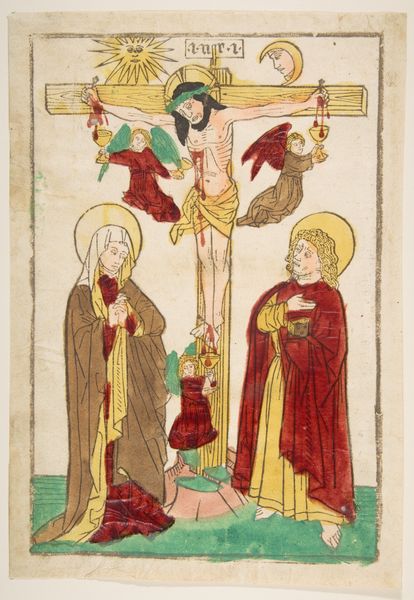

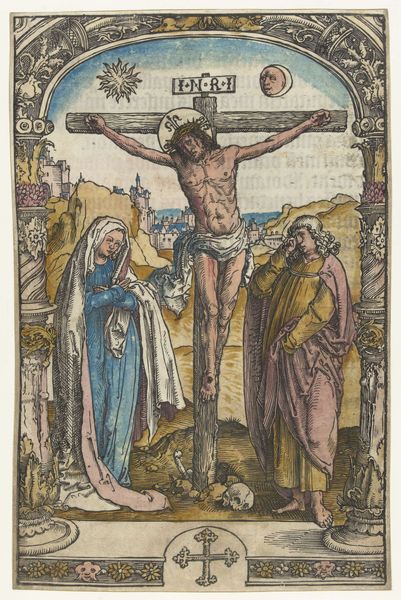

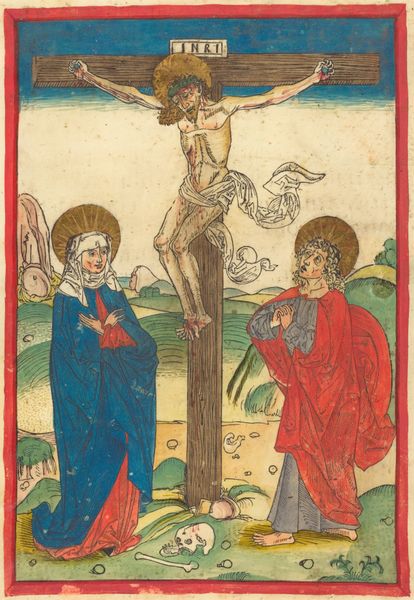

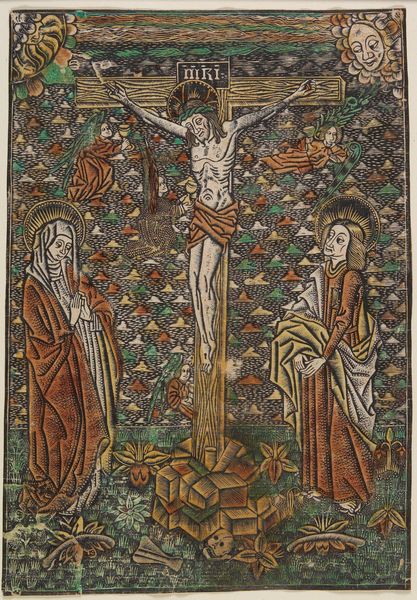

Curator: Here we have "Christ on the Cross," a woodcut print dating back to around 1490-1500, created by an anonymous artist in the Northern Renaissance style. Editor: It’s arresting, isn't it? The bright colors, the stark representation of suffering… there’s something almost unsettlingly direct about its emotional impact. Curator: Absolutely. Prints like this circulated widely, playing a crucial role in shaping religious beliefs. Its accessibility made it an extremely powerful tool. Editor: I find the figures to the sides interesting. Mary, on the left, draped in blue, embodies grief, but the figure to the right seems more…confrontational? Less passive, somehow. It disrupts a typical devotional narrative. Curator: It’s fascinating how such prints fostered collective piety. Imagine a community viewing this image together, each responding in their own way, solidifying shared values. This print circulated when the Church's role in society was rapidly shifting in Europe. Editor: You know, considering the ubiquity of crucifix imagery throughout history, what is it about this particular depiction, with its rawness, that perhaps challenged established artistic or societal norms? It does feel unusually forthright. Curator: It comes down to this shift in art production and distribution—a departure from the tradition of devotional artworks reserved for elite patrons or ecclesiastic purposes. The printing press helped the masses visualize their beliefs. Editor: It’s compelling to think about this print within a broader landscape of power and representation, particularly in terms of the Church. What does its creation and proliferation tell us about individual piety versus the institutional power that attempts to shape it? Curator: Precisely! It's also significant to note the technical aspects—the texture imparted by the woodcut technique itself lends a unique feel. It makes for compelling, replicable imagery. Editor: It gives you pause, doesn't it? The scale seems relevant too. It isn't grandiose. It encourages intimacy with this image, fostering perhaps a more radical and direct engagement with themes of suffering and faith. Curator: Considering the political, artistic, and socio-economic status in that era is what I think is the key. Editor: It brings into view the complexities surrounding the power and politics imbedded in images throughout history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.