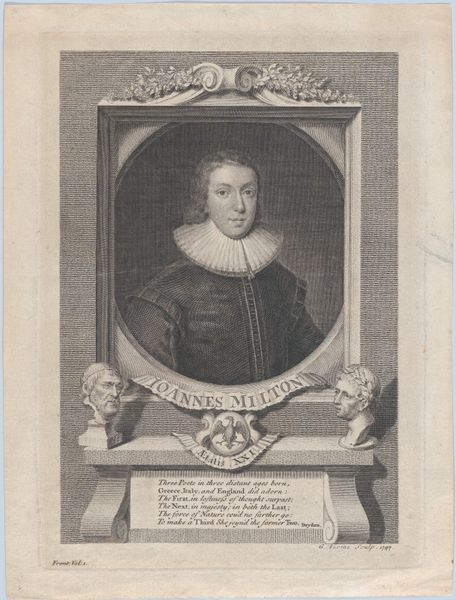

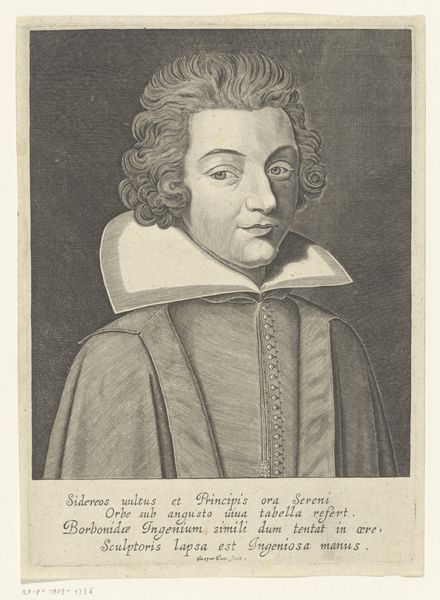

Mary, Queen of Scots (frontispiece, from "Theater, von Schiller," volume 4) 1807

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclassicism

# print

#

caricature

#

portrait reference

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 6 7/16 × 4 1/2 in. (16.4 × 11.4 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So, here we have an engraving from 1807, "Mary, Queen of Scots" by Autenrieth, serving as a frontispiece for a volume of Schiller. It feels...stark. All those precise lines of the engraving; what can you tell me about it? Curator: Stark is a great way to put it. Let's think about the context of printmaking at the turn of the 19th century. The Industrial Revolution was gaining momentum, and printmaking, like engraving, became a method for wider circulation. What impact does that have on art and knowledge? Editor: So it's not just about aesthetics; it's about access and the means of production. Because engravings are more reproducible than painting or drawing... Curator: Exactly. Consider the social impact of easily distributed images, especially in a period fascinated by history and celebrity. Schiller's play on Mary Queen of Scots would have fueled demand, and engravings fed that desire. But look at the *labor* involved. This wasn't painting – it demanded intense craft, translating emotion into etched lines. Editor: And those lines *are* so precise! Does that affect the meaning or the impact of the portrait? Curator: Definitely. Think of Neoclassicism as an aesthetic aligning with emerging industrial principles: rationality, control, standardization. It affects the *labor* to manufacture the portrait, which ultimately impacts viewership through the circulation and the narrative itself. Do you think the clean lines convey objectivity, or something else? Editor: It's interesting to consider the print itself almost as a manufactured product, reflecting the era’s values as much as Mary’s image. So it’s about materiality and reproducibility! I never would have thought of that, to be honest. Thanks for enlightening me! Curator: Precisely. Looking at art this way gives it all so much depth.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.