print, photography, gelatin-silver-print, architecture

#

print photography

#

16_19th-century

# print

#

landscape

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

street-photography

#

photography

#

natural colour palette

#

egypt

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

architecture

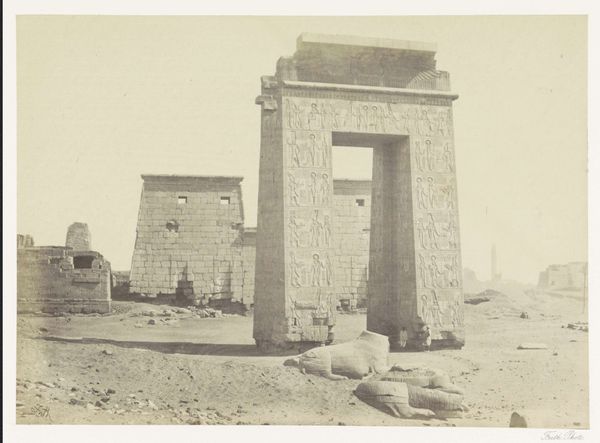

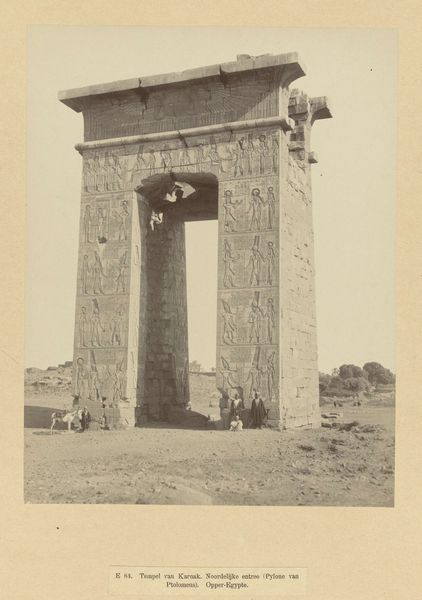

Dimensions: 15.7 × 23.4 cm (image/paper); 29.2 × 42.6 cm (album page)

Copyright: Public Domain

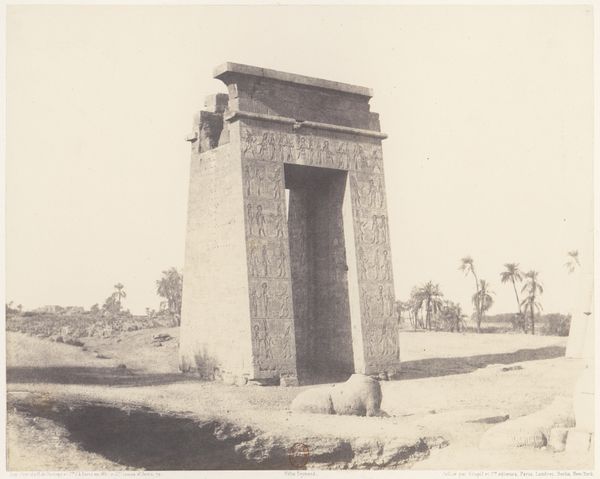

Curator: Here we have Francis Frith’s “Sculptured Gateway, Karnac,” a gelatin silver print taken in 1857. It resides here at the Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: Immediately, I’m struck by the sheer mass and weight of the gateway. You can practically feel the desert grit embedded in the stone. Curator: Absolutely. Frith, a master of early landscape photography, captured not only the scale but also the symbolic density. Look at the figures carved into the stone; they tell stories, record histories, and speak to beliefs about power and the divine. Editor: And what labor went into constructing something like this? Quarrying, transporting, carving—the social and economic organization behind it is just mind-boggling. It forces you to confront ancient systems of power. Curator: Precisely. Each carved figure holds a meaning—pharaohs, gods, offerings. Consider the orb above the gate: a classic symbol of the sun god Ra, representing creation and kingship. The gateway itself isn’t merely an entrance, it's a threshold to a sacred realm. Editor: These images have served so many purposes and masters. Initially charged with the state power of the Egyptian empire and its elite classes; subsequently repurposed into colonial trophies for Western audiences hungry for orientalist projections of power. It’s all encoded here. Curator: Frith was very intentional. His photographs catered to Western fascination with Egypt but he also brought back invaluable visual records, documenting sites like this one with scientific precision. It allows us to see a sliver of the past through his lens. Editor: It’s a powerful thing to ponder what these ruins signify now, juxtaposed against the forces that brought Frith, his camera, and his colonial project there in the first place. Curator: This photograph holds layers, then—layers of cultural meaning and historical implications captured in light and shadow. It still invites questions about what endures and what is lost. Editor: Yes, and how art always serves somebody—for better or worse. Food for thought in every weathered line.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.