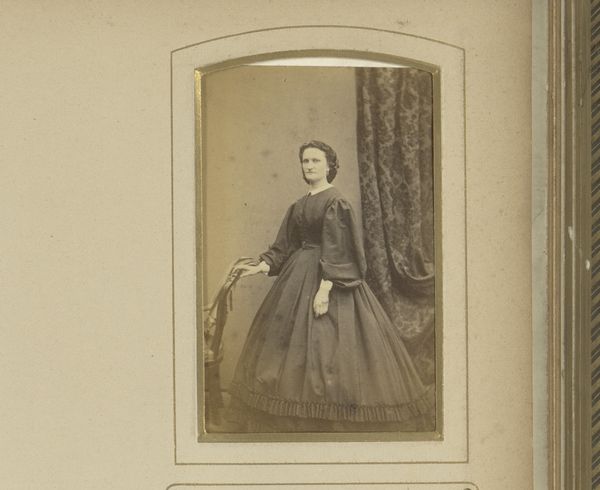

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

figuration

#

photography

#

genre-painting

#

albumen-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 53 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Immediately, I get this very quiet, introspective vibe. It’s a portrait, sure, but there’s a feeling of withheld stories. The way she gazes off to the side—wonder what she's contemplating. Editor: This is an albumen print, created sometime between 1860 and 1900, titled "Portret van een vrouw, staand bij een stoel" or, "Portrait of a Woman Standing by a Chair." It's by C. Hunneman. The choice of albumen printing in this era solidified photography as a primary form of social and personal documentation, creating accessible avenues for personal, societal and institutional image production and collection. Curator: Albumen prints... that gives it that delicate, almost ethereal quality, doesn't it? I can practically smell the dusty photo albums, imagine hushed parlors and families gathered around these tiny glimpses of their past selves. The very process sounds romantic and old. It’s like holding a captured whisper of history in your hands. And that dress... talk about making an entrance even when you're standing still. It practically anchors her to the earth! Editor: It's remarkable how that fashion serves as both a means of self-expression and social conformity for the period, really marking this lady’s class status within a set of constraints, almost as though to show that the picture’s symbolic potential is delimited by certain aspects of photographic reproduction. It's an intriguing visual tension. These weren't candid snapshots. Portraits were consciously staged to convey a certain message and control perception, often with the trappings of class status on full display. Curator: Yes, you’re totally right about it not being candid—I guess I was romanticizing that. I do wonder, though, if she got a little something of herself into the picture? It has to be hard to scrub every bit of personality from a photograph. Do you see anything, any gesture, that could point us toward who she actually *was*, outside her role? Editor: The averted gaze you noticed is interesting, especially considering photographic posing conventions in this historical moment. We need to keep asking ourselves—are we really seeing a portal to her essence, or just reading social symbols like clothing and class anxiety backwards? After all, portraiture exists primarily as a marker for someone’s existence at the level of societal and cultural memory. Curator: Maybe the answer is in that half-turned head—is it reticence or resistance? Ultimately it's left for the viewer to decide how those signals add up to what they call 'personality.' And that is probably why I find it to be so quietly striking— it doesn't answer; it prompts us to inquire about the gaps. Editor: Precisely, that silence becomes the photograph's most resonant statement about a past time. The fact is we cannot ever know this lady truly but must satisfy ourselves in thinking through the systems and structures that enabled and limited this picture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.