photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

Dimensions: height 100 mm, width 63 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

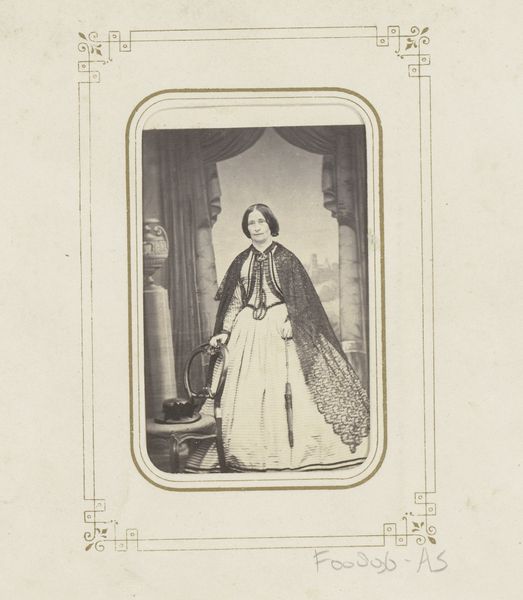

Curator: This is a gelatin-silver print titled "Portret van een vrouw," or "Portrait of a Woman," made sometime between 1858 and 1872 by Charles Thomas Newcombe. It presents a woman formally posed. Editor: My first impression is one of somber elegance. The tonality, the formal attire... it feels constrained. But there's also a certain dignity to it. The sheen on her dress suggests a careful attention to the fabrics involved. Curator: Indeed, that's reflective of the era. Photographic portraits at that time carried a weight of memorial. This image offers a glimpse into societal expectations, where formality signaled respect and lasting presence, as if each element tells a story of that world’s visual and material culture. Editor: The materials tell a story of class as well. This isn't a candid shot; it speaks of resources and access to a relatively new technology. The dress alone, likely silk or satin, would have represented a significant investment, not just financially, but also in terms of labor needed for its creation. Curator: Right. And observe her adornments—the string of beads and that simple yet sophisticated hairstyle. It communicates not just her social standing, but a cultural emphasis on restrained beauty. It evokes Victorian ideals of domesticity. It contrasts how self-portraiture is conceived today in modern terms of instant access. Editor: The way her hand rests on the table interests me. It’s almost like a prop, underlining her confinement, a gentle constraint echoed by the very frame surrounding the photograph. One can feel a history of access and materiality present in such pieces of studio photography. Curator: And isn't that precisely what endures? It transcends just a mere image. These portraits act as coded narratives, laden with symbolisms regarding the period and the figures captured within these emulsion confines. They continue to serve as conduits connecting us to a past. Editor: Absolutely. Examining it this closely reveals the tangible conditions in which such an image was realized—a material record far more potent than any romanticized narrative alone. I can almost feel the process within this image, and the artist who developed this print. Curator: It also allows one to engage intimately with how we see and give importance to even the seemingly everyday facets of past human existence. A great testament for the cultural study of visual imagery of humanity itself. Editor: Yes, by engaging closely with objects and how these were made, we unlock far greater meaning than ever initially perceived at first glance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.