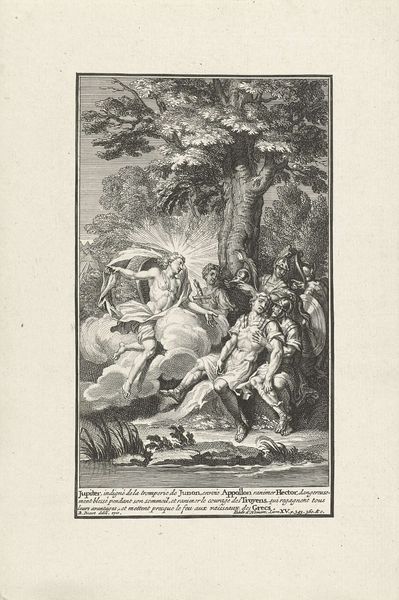

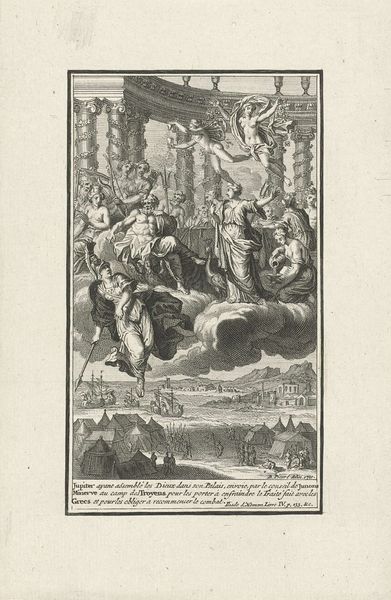

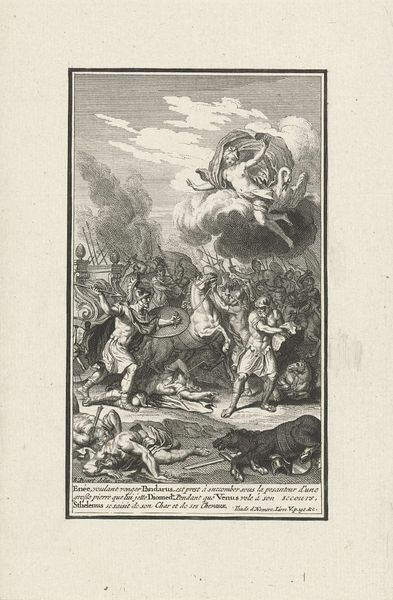

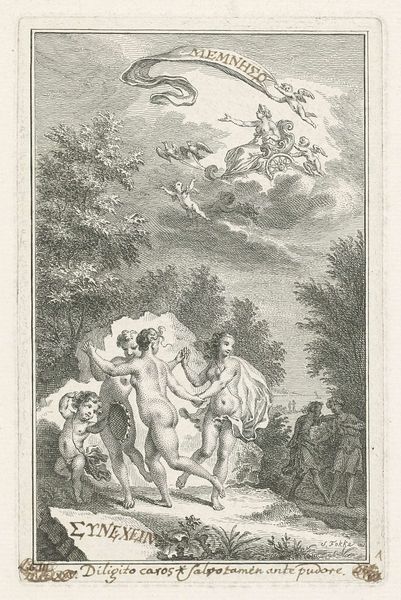

print, engraving

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 188 mm, width 123 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Bernard Picart’s engraving, “Juno Verleidt Jupiter,” made in 1710. It's striking how dynamic it is, even in a static print. It makes me think about depictions of power… So, how do you interpret this work within its historical context? Curator: Considering the print’s public role at the time, the choice of Juno and Jupiter isn’t just mythological—it’s politically loaded. Depictions of mythological figures provided a way to talk about power dynamics in court and in wider society. How do you think the social position of Picart, relative to the patrons, affects the viewpoint presented? Editor: I suppose as an artist he might be critical of the ruling classes but simultaneously beholden to their tastes for his success… Curator: Precisely. Consider the Baroque style itself. Its grandeur often served to glorify powerful figures, yet prints allowed wider access to such imagery. The "realism" tag is particularly interesting here, since Baroque prioritizes dynamic scenes, which is somewhat antithetical to realism. Are we really getting realism, or is this drama crafted for effect? Editor: I see what you mean! It's not about capturing everyday life but staging a persuasive scene, like political theatre almost. Curator: Exactly. And the engraving as a medium facilitates this dissemination, which further reinforces the political undertones present. So what have you discovered about your perception? Editor: That initial impression was a surface reading! Looking closer, it’s fascinating how political statements were made through allegory and artistic style. Curator: Indeed! The public role of art wasn't just aesthetic, but fundamentally entwined with social power structures.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.