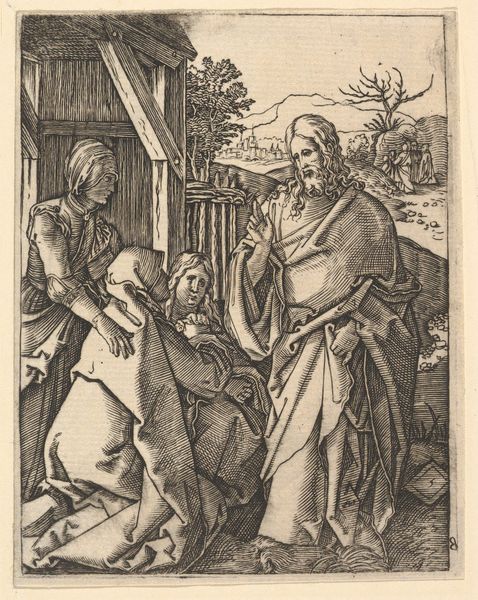

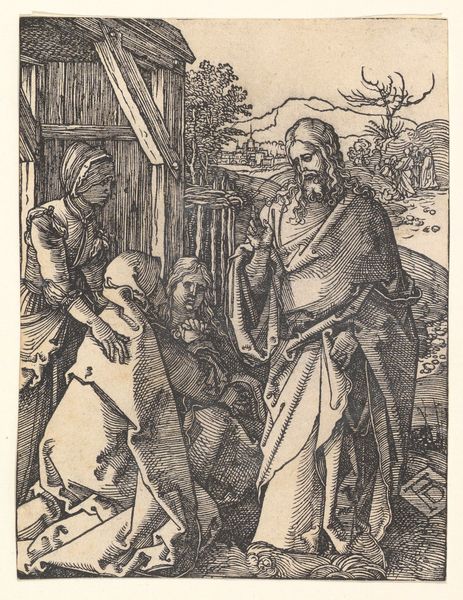

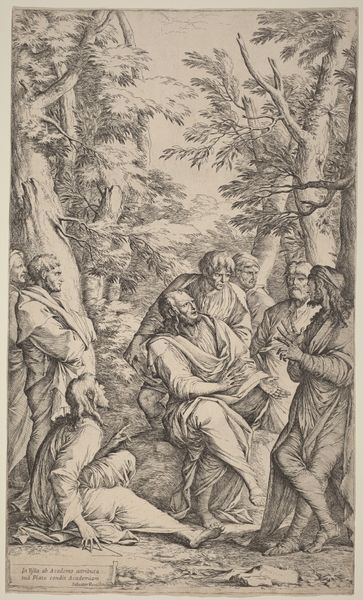

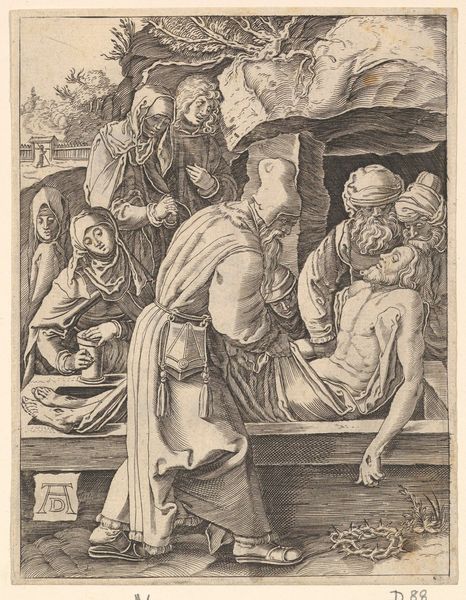

drawing, print, woodcut, engraving

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

# print

#

figuration

#

woodcut

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: For the whole series: plate circa : 5 x 3 13/16 in. (12.7 x 9.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have what's referred to as "Engraved copies of The Little Passion," a work that spans from 1485 to 1699. This print, showcased here at The Met, originates from the hand of Albrecht Dürer. He's renowned for his skill in engraving and woodcut, bringing together both medium in a distinctive Northern Renaissance style. Editor: The composition immediately strikes me— the figures clustered so tightly against the detailed background landscape. There's a sense of vulnerability. It feels like we’re intruding on a very personal moment. Curator: Indeed. Dürer, in his role as an artist working during the Reformation, often tackled religious narratives. Consider the socio-political implications: disseminating biblical stories through affordable prints to a wider public. What was previously the purview of the Church was now available to the individual believer for study and contemplation. Editor: It’s interesting that you point that out; I mean, it wasn’t just about democratizing access. Think about the very power dynamic being depicted here: Jesus offering solace. Who are these women seeking help? What does it mean to depict that level of raw, emotional dependency during that era? Dürer isn’t merely illustrating; he’s engaging in the social anxieties and spiritual hungers of the time. Curator: It’s clear the artist wanted to instill religious teachings with both precision and empathy. Look closely, you can really see Dürer’s influence throughout Europe as a number of contemporary and subsequent artists copied his pieces to disseminate the story. This explains the phrase ‘engraved copies.’ Editor: So, not necessarily the artwork that the masses saw, but still it has Durer’s original essence? Curator: Precisely. These copies demonstrate Durer’s vast reach. But as you consider its role in shaping perceptions, how might the artistic interpretation—the very deliberate staging and expressiveness—have guided personal connections to these religious narratives? Editor: Right, the narrative becomes almost... personal. The small size of these prints contributes too— you can almost imagine people carrying them for private contemplation. It moves the divine from the church alters into everyday lives. Curator: Yes. Looking at this print really does reveal the fascinating intersection between art, religious practice, and early print culture. Editor: Agreed. It’s also a potent reminder of art's unique position in interpreting history and challenging those in power, even when those stories were replicated or changed, the seed was still there.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.