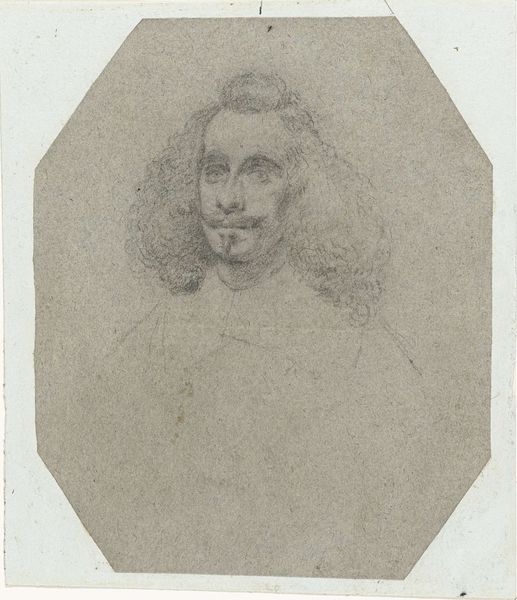

Portret van een (Spaanse?) heer, ten halven lijve, naar rechts before 1650

0:00

0:00

gerardteriiborch

Rijksmuseum

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

realism

Dimensions: height 152 mm, width 126 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let’s consider this striking drawing, attributed to Gerard ter Borch II, "Portret van een (Spaanse?) heer, ten halven lijve, naar rechts,” made before 1650. The piece is a pencil drawing, currently held in the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: My first impression is one of intimacy; the pencil sketch feels like a private glimpse into the life of this gentleman, maybe even a study for a larger, more formal painting. It’s quite understated. Curator: Yes, the directness of the pencil lines offers a feeling of immediacy. Ter Borch was deeply interested in capturing the subtleties of human expression. Considering the subject’s possible Spanish identity, how does the portrayal engage with, or perhaps subvert, prevailing stereotypes about Spanish nobility during that period? The "Spanish Question" was a highly charged, often politicized theme during the 17th century. Editor: Interesting. For me, looking at the production itself, I'm wondering about the type of paper used, the specific pencils that would have been available, and the social context of draftsmanship at the time. Pencil sketches would not have been considered autonomous works in this period, they were material means towards an end. Curator: Exactly! The means of production inevitably impact the final representation. Pencil, as a less 'refined' medium than oil paint, grants the artist certain freedoms. How might the relative accessibility of the medium influence who gets portrayed and why? Was this a preparatory drawing of an aristocrat, a commission, a friend? Perhaps ter Borch also wished to democratize portraiture. Editor: It is difficult to ignore that the means of displaying such a work has also transformed—today we consider this sketch an artwork of notable value, displayed in one of the most well-regarded art institutions. That elevation of material production seems worthy of consideration in a social sense. Curator: Absolutely. Viewing it today, we project our contemporary understanding of value onto it. But interrogating its genesis – its materiality, its intended function, the sitter's social standing – allows for a richer, more nuanced reading of this fascinating piece. The drawing’s survival also prompts considering who gets archived, saved, preserved through institutional structures. Editor: This little drawing raises big questions about process, status, and what it even means to create an "original" in the early modern period!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.