#

portrait

#

amateur sketch

#

facial expression drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

charcoal drawing

#

portrait reference

#

pencil drawing

#

animal drawing portrait

#

portrait drawing

#

facial study

#

digital portrait

Dimensions: height 226 mm, width 170 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

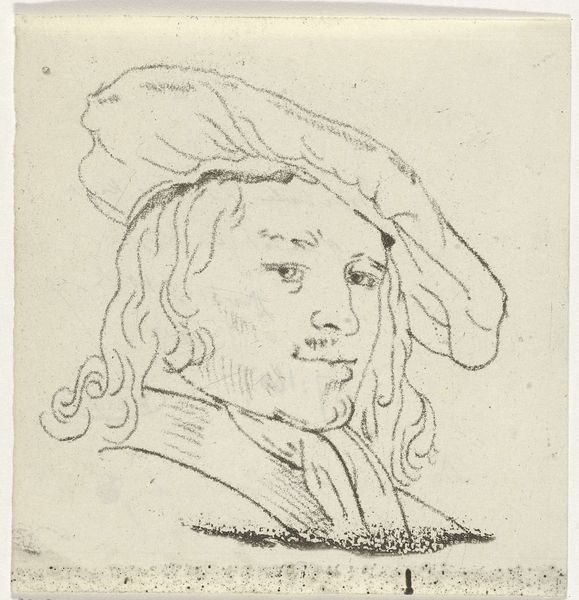

Curator: This drawing, housed here at the Rijksmuseum, is cataloged as a portrait of Gerard Dou, dating roughly from 1700 to 1725, and attributed to an anonymous artist. Editor: My first thought is: remarkable linework. The artist beautifully captures light and texture with what looks like red chalk. Curator: Indeed. Looking closely, we see an emphasis on capturing the likeness, but within a specific social frame. Consider the sitter’s garments; the elaborate hat and long, styled hair signal wealth and status in the Dutch Republic of that time. The drawing begs questions about class, power, and how they're visualized through portraiture. Editor: Absolutely, but let’s not forget the material reality. Red chalk was a favored medium for studies and preparatory sketches, cheaper than paint, so its use here possibly speaks to the process. It wasn't necessarily meant as a final, presentable image, but to document or to practice. Did this anonimous artist create this drawing as part of an apprentice or just for the purpose of his art? Curator: An important observation. Perhaps the 'finish' wasn't the priority; the immediacy of the sketch allows us access to a rawer depiction of a prominent man. It almost feels… vulnerable. This tension –wealth and status, depicted via what might be called simple means—offers interesting insight into the representation of identity at this time. Is this how artists represented this powerful identity? What was going on? What struggles were going on during that time that is expressed with simple materials and simple means of execution? Editor: And how available and standardized was red chalk around this period? Considering the access to and price of different materials often allows me to more closely align artwork with its context, connecting class, skill and the raw process of the act of making art. Curator: Precisely. Considering accessibility brings us full circle, revealing an intersection of artistic practice, subjecthood, and social standing. It forces us to reconsider historical binaries, bridging “high” art with labor and even perhaps gender when assessing creative contributions. Editor: Right. So even with this unsigned portrait done in a modest medium, we can glean something significant about the Dutch art world and society that shaped the work itself. The materials are never neutral. Curator: Anonymity isn't neutral, either. Who wasn't recorded and what was at stake for them at this time? Editor: A question for another time. Thanks.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.