print, woodblock-print, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

asian-art

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

#

woodblock-print

#

history-painting

#

cartoon carciture

#

engraving

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

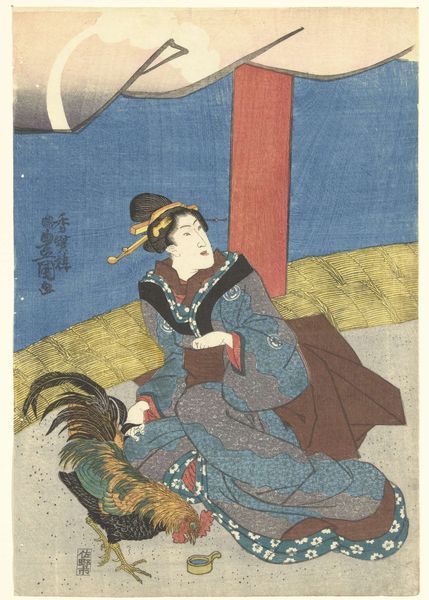

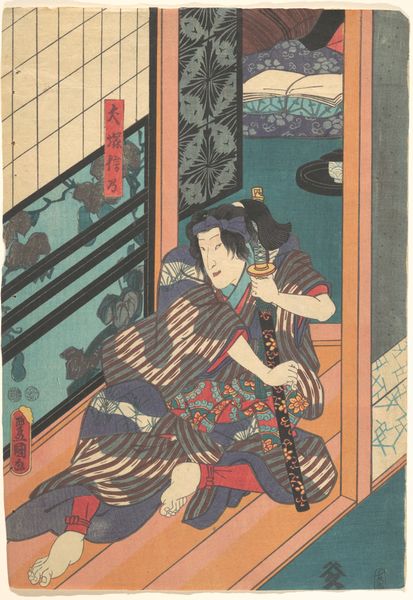

Editor: We're looking at "The Woman Kansuke Slaying an Assailant with a Sword," a woodblock print made in 1866 by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi. The intensity of this scene really jumps out—the dynamic pose, the colors, but the characters’ faces are what make me stare! What strikes you when you look at this, Dr. Armitage? Curator: Oh, darling, it's the theatricality, isn’t it? It's high drama in every meticulous line. This isn’t just a depiction of violence, it's a story being told—or rather, sung, like a Kabuki performance frozen in time. Can you sense the "kata," the poses, passed down from generation to generation, and the story immortalized by being transferred into block prints, to be relived in common homes? I almost wonder who this "Woman Kansuke" *really* was... Perhaps the story has more fact in it than we assume. Editor: The “frozen Kabuki” vibe makes a lot of sense. But why do you mention fact, shouldn't we expect historical narrative here? Curator: In a way, it may depend what we expect of "historical". These prints weren't always about objective history with a capital H. Often, it's a more...shall we say, embellished reality? It is always a political narrative. The artist uses history to speak to *his* time, Yoshitoshi certainly did so at a time when the Tokugawa shogunate’s power and prestige was rapidly declining, making this all seem slightly subversive. How much agency does Woman Kansuke take? Do we feel as if it glorifies such behaviour? These are the key issues to dissect. Editor: Subversive, and timeless. Thanks for pointing out those subtleties – really shifts how I see it now. Curator: Art reveals secrets, doesn't it? Or whispers them in our ear if we allow them.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.