Dimensions: height 187 mm, width 239 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

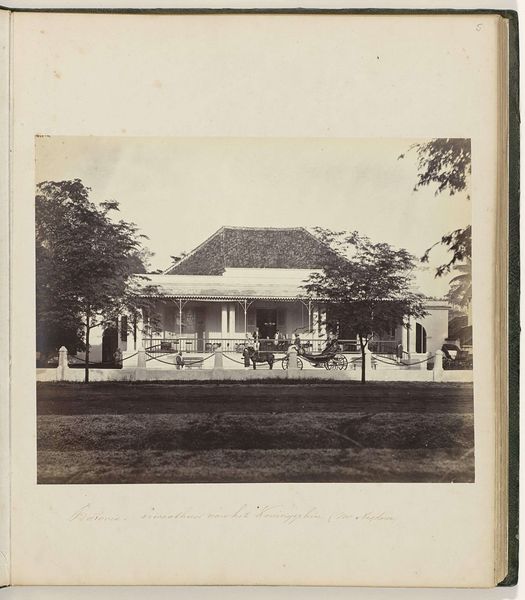

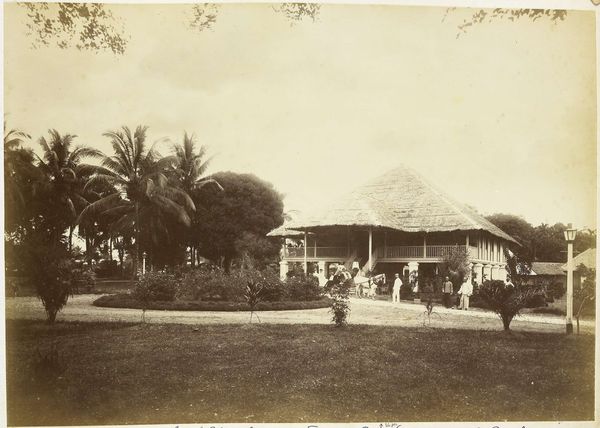

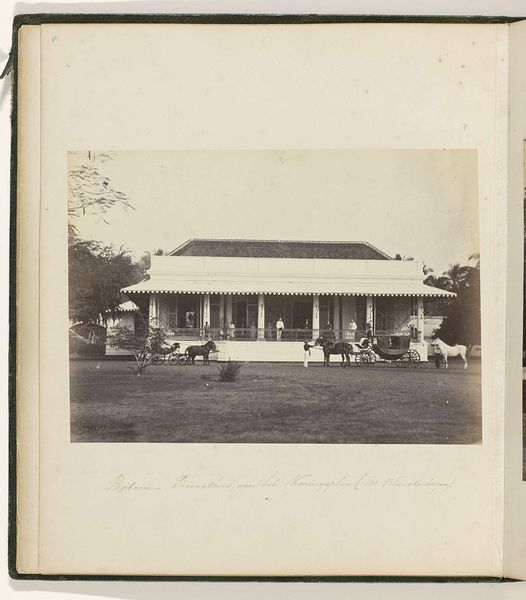

Curator: What a fascinating image, don't you think? We're looking at "Samarang - Privaathuis (mr de Joannis)", an albumen print created sometime between 1863 and 1869 by Woodbury & Page. It's held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: There's a stillness to it that's captivating. Almost feels staged, wouldn't you say? A large group posed rigidly in front of what looks like a grand residence... everything feels very composed, very proper. Curator: Proper indeed! Woodbury & Page were well-known for their portraits and genre scenes reflecting the colonial life of the Dutch East Indies, so we have to keep in mind the context in which they operated and who their patrons were. It's important to consider this within the larger context of Orientalism, and think critically about the dynamics of power at play here. Who is represented and how? What narratives are being reinforced? Editor: Right, right, of course. The power dynamics are practically radiating off of it. You almost get the impression they're showcasing a vision, meticulously crafted for the colonizers back home. Look at how the building looms, an architectural statement imposing itself upon the landscape. Curator: Exactly! The home becomes a stage for a carefully constructed narrative, one that subtly affirms a sense of dominance and cultural superiority. Even their attire is very indicative of class and race dynamics; notice the clear distinction between the Europeans and any native inhabitants present in the frame. The local population often worked as domestic help. How are they positioned? Are they at the forefront, or deliberately pushed to the background? These are crucial factors to think about when examining Orientalist works. Editor: Yes, all very interesting, of course, though for a moment I find my attention captured by the textures... the intricate patterns of the roof tiles, the flow of light through the open veranda. Photography, so young at the time, already displaying its capability to capture these subtle visual pleasures, wouldn't you agree? It makes you think. Who were these people really? Did they know their photograph would become the silent ambassador for an era of cultural and colonial tension? Curator: Absolutely. A photograph can become an unwitting historical witness, raising profound questions. It's crucial for us to explore and probe the layers of complexity woven into images like these. They continue to spark necessary, though uneasy conversations, regarding historical representation and ongoing consequences of colonial legacy.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.