engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 254 mm, width 175 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

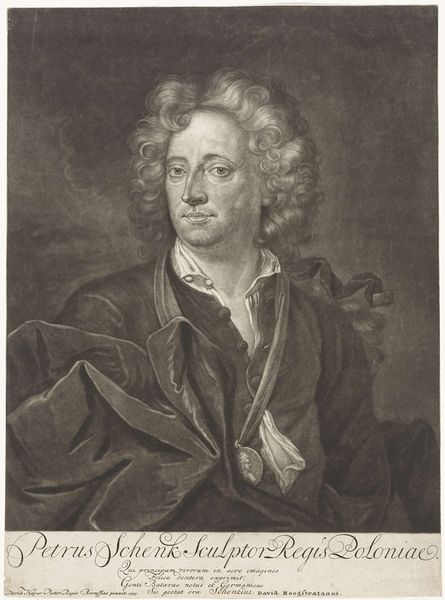

Curator: We're looking at an artwork by Pieter Schenk, who portrayed himself in this self-portrait executed between 1697 and 1713. This particular piece is an engraving and resides in the esteemed collection of the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by the contrast! The use of light and shadow is superb, creating a sense of depth despite the medium. And there’s this almost theatrical quality, an implied narrative. Curator: Indeed! Consider the period; this engraving emerges during the Dutch Golden Age, a time where portraiture, even self-portraiture, often served specific functions related to constructing identity and securing patronage. His gaze, directed at the viewer, makes this an act of self-promotion within specific networks. The artist presenting himself through calculated artistic gestures to promote his artistic skill and elevated societal position. Editor: But look closer: the fine lines, the details in the hair, the subtle gradation of tone. It draws the eye inward. Also, there is this heavy reliance on tonal contrasts, a sophisticated technique that emphasizes the volume and texture of the garments and, naturally, of Schenk's features. Curator: And we must also think about how he represented himself within the framework of gender and status expectations. Think about that neckwear for instance, what is that communicating, considering his profession? The subtle presentation is a performance of a man conscious of how others perceived him and wanting to communicate something to his audience. Editor: You raise a fair point, but without necessarily considering the context, I find myself appreciating how Schenk manages to capture, with such limited means, a real sense of flesh and blood—a human presence beyond the symbols of status. Curator: By understanding this in a more encompassing context, we can go beyond his mastery of engraving, delving deeper into self-fashioning as a political action during a transitional time in art history, where one’s art also acted as your calling card and proof of existence. It highlights the complex negotiations of self-presentation for artists during that era. Editor: So, by merging your sociocultural assessment and my close inspection of form, a deeper reading is made, enhancing this beautiful work as a key artefact in understanding society itself. Curator: Precisely! It becomes more than a self-portrait—it’s an engraving, but moreover a reflection of identity within its period and location!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.