oil-paint

#

still-life

#

impressionism

#

oil-paint

#

oil painting

#

geometric

#

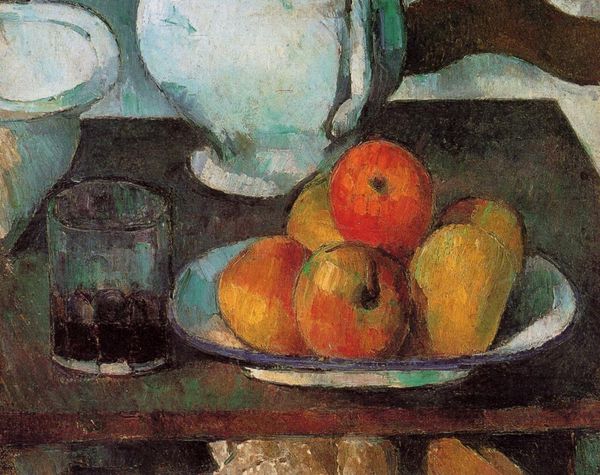

post-impressionism

Dimensions: 46 x 55 cm

Copyright: Public domain

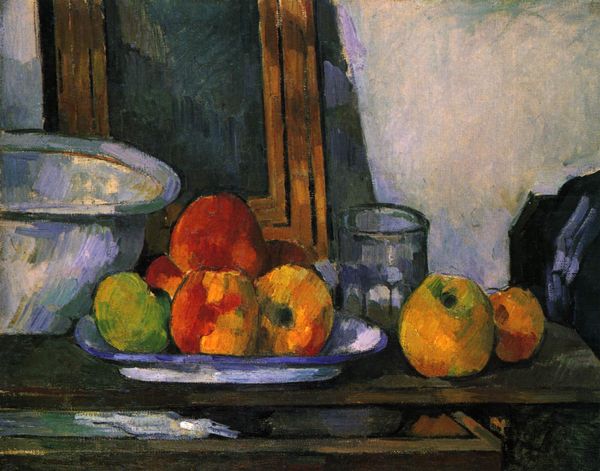

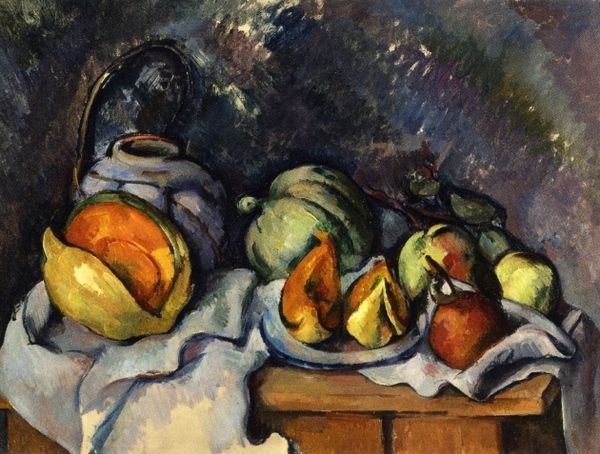

Curator: So, here we have Paul Cézanne's "Compotier, Glass and Apples," dating back to around 1880. It's currently held in a private collection. Editor: It's fascinating. The immediate impression is one of...sturdy instability, wouldn’t you say? Those apples feel more like painted rocks. I can almost smell the linseed oil, what do you think about this materiality here? Curator: Precisely. It reflects a critical point in art history. This was painted at a time when the establishment prized illusionism and polish. Cézanne, however, focuses on exploring the underlying structures of the objects he paints, using that materiality. Editor: I'm thinking about how much preparation went into producing something seemingly simple and that there were many steps involved from production of pigment and textile all the way to distribution. This aesthetic choice reveals that kind of labour and reminds us that those processes require raw materials. What is the statement that the artist makes when his art becomes more about materials and not what is depicted? Curator: Good question. The deliberate lack of perspective—look at the table's edge—was initially scandalous. It challenges academic norms and starts the move away from purely representational art and lays some groundwork for movements like Cubism, reflecting early modernism’s questioning of established power structures. Editor: Absolutely, Cézanne makes us think about how fruit gets on our table by challenging high art with the depiction of commonplace things, it questions our social habit to place still-life at a very low position in the art hierarchy. How about this rejection of traditional perspective that puts the painting on the trajectory of art movements in the 20th century? Curator: Absolutely. He rejects perspective to give a multi-faceted and subjective view. It asks the viewer to reconsider their own position in relation to the world and marks a shift in the role of art. It ceases to be a mere representation, now asking social questions. Editor: It does that and lets us know a painting is always about paint, even though for centuries paintings would disguise the marks, materials and human labor to make it, there is something so fresh and urgent in reminding the world this art making rule. Thanks to paintings like these we can acknowledge the history, labor and materials involved with the creative process.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.