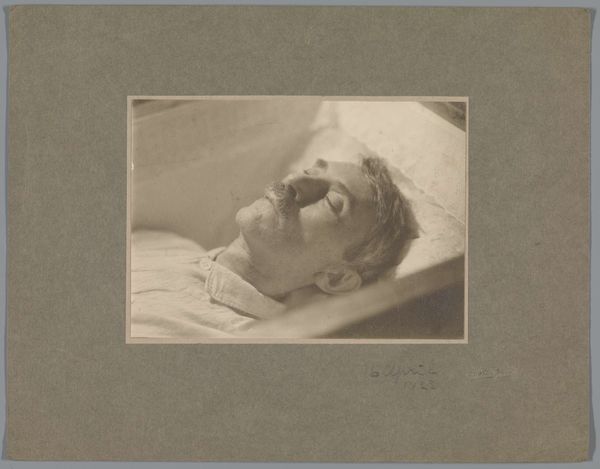

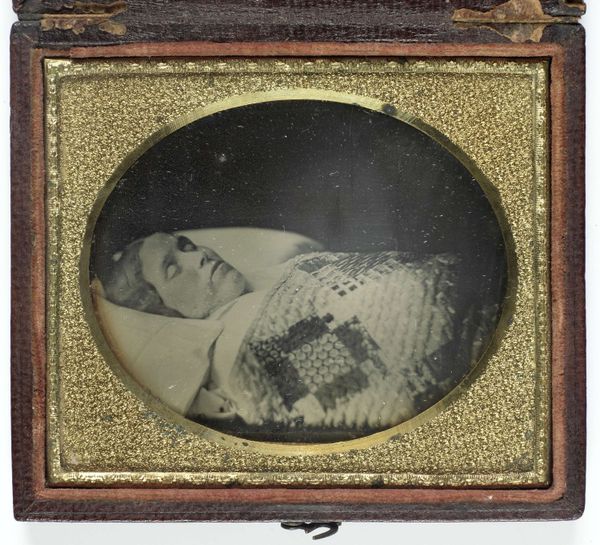

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

albumen-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 88 mm, width 63 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is a post-mortem portrait of an unknown man, likely taken sometime between 1863 and 1884. It's an albumen print photograph. There's a stillness to it that’s quite unsettling. What do you make of this photograph? Curator: It’s a chilling example of a once relatively common practice, reflecting societal attitudes toward death and mourning during the Victorian era. What we now consider macabre was then a way to preserve the memory of the deceased, especially of children, who sadly had lower life expectancy. Editor: A way to preserve memory... I hadn’t thought about it that way. It feels almost voyeuristic to us now. Curator: Indeed. But consider the context: photography was still relatively new. These post-mortem photographs provided a tangible "last look" during a time before snapshots were ubiquitous. They played a vital role in the rituals surrounding death. These images weren't necessarily viewed publicly in the same way we consume images today, so should that effect how we perceive it as a "public" work? Editor: That's fascinating. So, you're saying it was more about private remembrance than public display, which really shifts my understanding. Curator: Exactly. And the “realism” that photography offered was believed to provide a truer representation than a painted portrait. So how does that truthfulness effect the modern perception of the sitter, as compared to a romanticized or fictional one? Editor: I hadn't considered the impact of realism either. It makes you wonder about the social class implications – who could afford such a memorial? Curator: Precisely. The economics and accessibility of photography played a significant role in who was remembered in this way. It's another layer of the story this photograph tells. Editor: This has given me a new perspective on post-mortem photography; I will now reconsider this work with fresh eyes. Curator: It illustrates how deeply art is embedded in social practices and economic realities; things often shift beyond just aesthetics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.