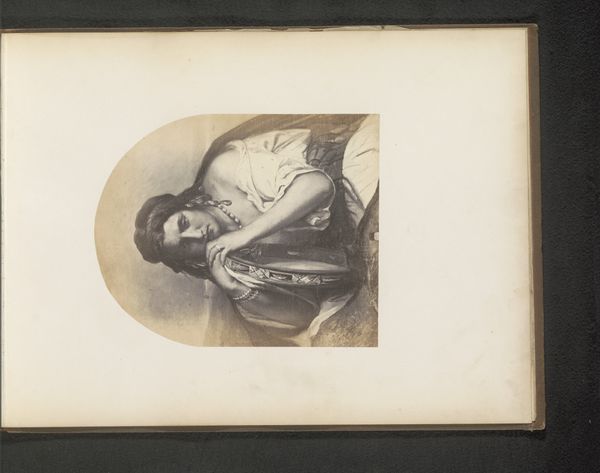

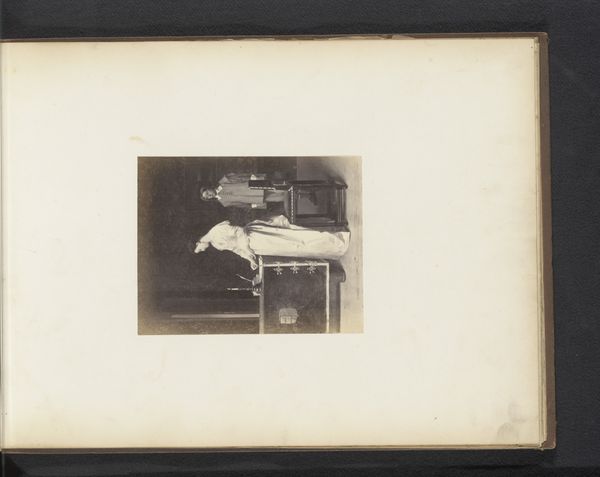

Private Dennis Sullivan, Company E, Second Virginia Cavalry 1865

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

soldier

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

men

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: Image: 13.1 × 18.9 cm (5 3/16 × 7 7/16 in.), oval

Copyright: Public Domain

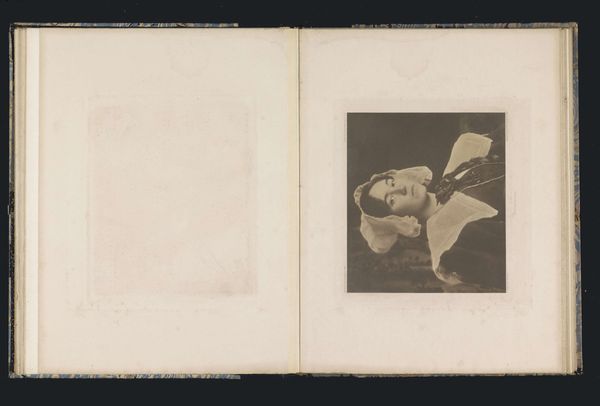

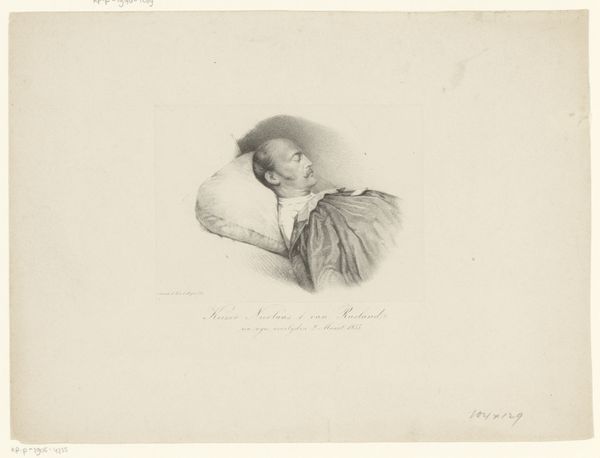

Curator: Well, this image just breathes a sort of solemn, haunting beauty. It’s like finding a whisper of peace amidst a hurricane. Editor: It’s a powerful image, indeed. This is a photograph titled “Private Dennis Sullivan, Company E, Second Virginia Cavalry,” created around 1865 by Reed Brockway Bontecou. It’s an albumen print, a technique that really captured the details of the time. It now resides at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Curator: Albumen... you know, that creamy egg white that gives the image such a dreamlike softness? There's a deep humanity to his relaxed face. It's intimate, like we are seeing someone slip between worlds. Does he just appear to be resting? Or… Editor: Bontecou, as a surgeon, documented many injured soldiers during the Civil War. Images like these became crucial not only for medical records but also, controversially, as public displays in galleries. There's a definite tension between the clinical observation and the emotional weight carried in depicting Sullivan. Curator: Yes, exactly, it makes me wonder how Bontecou managed the dual role of healer and recorder of these very real traumas. Was it scientific objectivity or quiet, visual grieving? Did the public know it was his body, after he passed, laid peacefully and elegantly for a camera, instead of left broken and torn, in agony on the field of battle? Editor: It raises huge ethical questions about consent, representation, and the sensationalism of war. Back then, galleries showing such images contributed to shaping public opinion. People felt they had a view into the reality of war, while distanced from the actual carnage. Curator: Do you think, looking at him now, laid out like this, people were more for the war, or against? This gentle look can make you stop and realize it really just ruins lives. Editor: Potentially. These portraits both humanized and perhaps, paradoxically, aestheticized suffering. The careful composition framed in its oval could soften its immediate blow. Today we wrestle with that same dynamic: how can images of suffering become a means to educate or galvanize without exploiting individuals. Curator: Well, next time I want to sleep, let's hope that I'm sleeping in the nice sheets and in the same position as Private Dennis Sullivan. So peaceful and elegant! I love seeing the way people look at these works and wonder and think, long after the flashbulb is gone. Editor: Precisely. And this image continues to speak— or whisper— to us, prompting reflection on war's impact, on ethical representation, and our role as viewers in the face of someone's death, however long ago it happened.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.