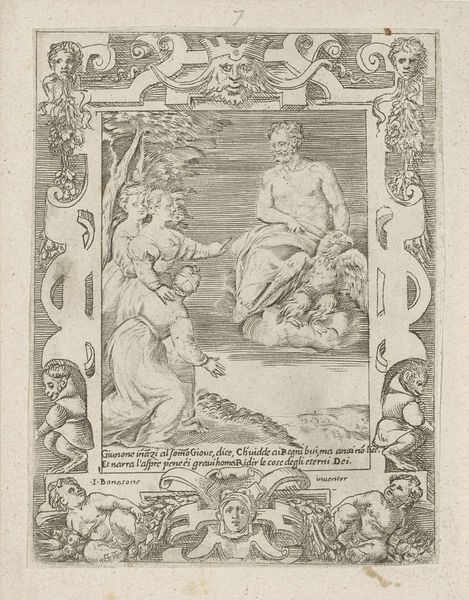

Dimensions: height 115 mm, width 95 mm, height 77 mm, width 55 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Wenceslaus Hollar’s 1651 engraving, "The Merchant and Death," now residing in the Rijksmuseum, is a striking example of vanitas imagery. My first thought is its potent allegorical statement rendered so sharply, like a moral lesson etched in metal. Editor: Yes, that initial jolt you get from the skeletal figure wrestling the merchant is palpable. I see how Baroque theatricality clashes head-on with the stark reminder of mortality. This really underlines the anxieties of the Dutch Golden Age concerning trade and earthly gains. Curator: Absolutely. The technique here—the intricacy of the line work achieved through engraving—demands our attention. Think of the labour involved! And this wasn't fine art to hang above your fireplace, but more for distribution, perhaps in books, readily accessible. This challenges notions of artistic worth tied solely to originality. Editor: The accessibility also extended to the visual literacy of the time. Consider the surrounding figures—putti, philosophers—acting almost like commentators in a Greek chorus. Their presence highlights the prevailing discourses on mortality, sin, and salvation, tightly knit within socio-political dynamics of colonial wealth and overseas commerce. The ocean backdrop hints at globalized trade that fuelled this society, but also introduced disease and human misery, something never separated from the goods they acquire. Curator: I agree; and this image operates on that double edge. We are presented with meticulously rendered detail and the stark contrast of line heightens the drama, guiding our eyes around the frame. We can trace its manufacture back to a single artisan—Hollar—yet see this print functioning across networks. Its value isn’t in some innate quality of 'beauty', but in its capacity to mediate larger anxieties. Editor: It speaks volumes to us today. "The Merchant and Death" prompts reflection, doesn’t it, on ethical consumption? It encourages one to question systems where certain peoples benefit from global markets steeped in inequity and, at times, dehumanization. Even 370 years later, it serves as a visual call for social justice and economic reform. Curator: Exactly, and from my perspective it reminds us of the tangible human effort necessary for these kinds of prints to reach their viewers, emphasizing the physical and the historical roots of art. Editor: In essence, this isn't just an image; it's a multi-layered mirror that challenges us both materially and morally, making it so valuable to this very day.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.