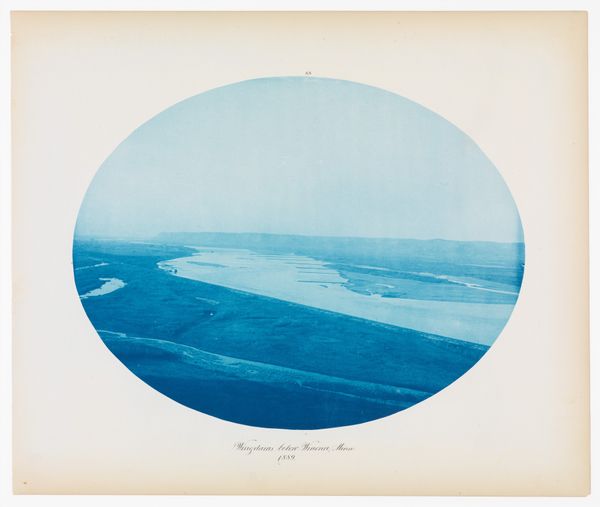

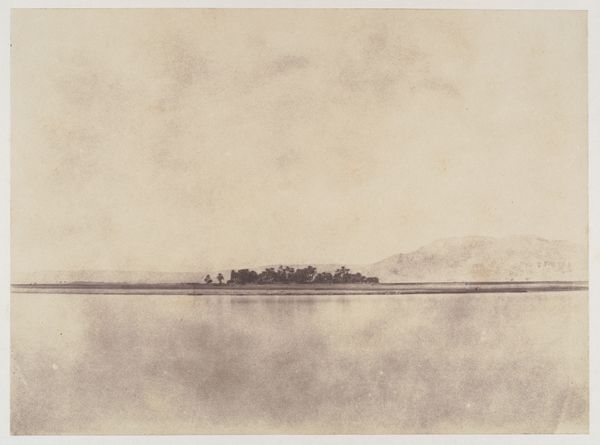

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

landscape

#

luminism

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

Dimensions: Image: 10 9/16 × 13 1/2 in. (26.8 × 34.3 cm), oval Sheet: 14 7/16 × 17 3/16 in. (36.7 × 43.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Standing before us is Henry P. Bosse's "Mouth of Wisconsin River" taken in 1885, rendered using a gelatin-silver print technique. It’s quite remarkable. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by the photograph's overall tonality. It is almost entirely one shade of blue. The composition, presented within that distinct oval, projects a serene and melancholic mood, almost otherworldly. Curator: It’s fascinating how Bosse, an engineer by trade, approached photography with such technical precision. This wasn't just about capturing a pretty picture; it was about documenting the river and its surrounding landscape, as industrialization was making its way into every corner of the state, for planning, engineering, or promotional purposes. His documentation of landscape carries an interesting confluence of labor, materiality, and record keeping, challenging a romantic picturesque interpretation. Editor: I find the composition so intriguing. The horizon line sits perfectly in the center, dividing the river from the sky almost equally. It draws the eye toward that vanishing point in the distance, using perspective to enhance that placid atmospheric effect. How do the material properties contribute to its aesthetic quality? Curator: Well, the gelatin-silver process itself, especially when carefully executed by someone like Bosse, allowed for finer details than earlier photographic methods. What we might read as mere aesthetics, for Bosse it meant achieving a higher degree of resolution, useful for technical analysis of this waterway. We also have to remember that at that time such processes meant long exposure times so to produce images, and consequently required immense amounts of labor. Editor: But the very limitations of the technology add to the effect! Those subtle tonal gradations enhance the luminous quality that one associates with luminism as a style, doesn't it? Bosse wasn't aiming to replicate reality exactly, even though that was arguably a function of the medium itself. This landscape isn’t just seen but felt. Curator: Exactly, it’s not solely the outcome but how Bosse, harnessing specific chemical and physical processes and the related industry practices, attempted to exert a form of control over this environment, using it as information. His labor intersects in interesting ways, blurring the boundary between scientific documentation and art making. Editor: Thinking about how Bosse shaped visual and emotional responses through such stark simplicity provides a good conclusion here. It invites reflection on the fusion of technology, aesthetics, and human perception. Curator: Indeed, by studying process we can glean far greater understandings to the intersections of society and industrialization that influenced its creation, moving beyond a merely beautiful scene.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.