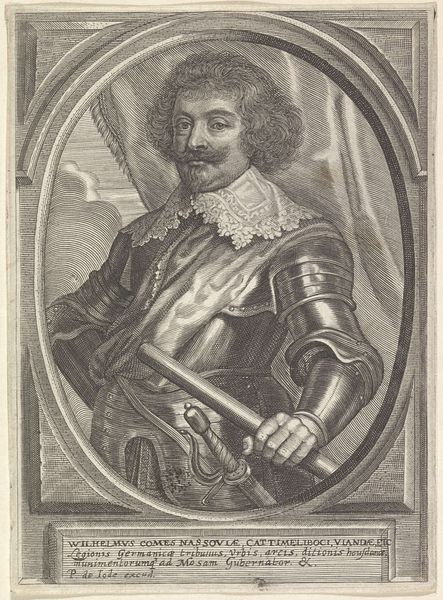

metal, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

metal

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 137 mm, width 91 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. We are standing before an engraving dating between 1610 and 1668, currently residing here at the Rijksmuseum. The piece is titled "Portret van Willem, graaf van Nassau-Siegen" and is attributed to an anonymous artist. Editor: Okay, so my first impression is this: a little heavy, right? Lots of ornate detail packed into a small space. He seems like he's taking himself very, very seriously. I find a surprising warmth in the hatching of the background, even given the severity of his stare. Curator: Precisely! Let’s unpack the elements. The Baroque style is unmistakable. The subject is framed within a complex oval cartouche, topped with a cherubic figure—a very popular iconographic feature during the Baroque era. Notice the strategic use of light and shadow through varied line weights. Semiotically, it suggests wealth and nobility through clothing. Editor: It's also, well, it’s almost claustrophobic. He's crammed into this tiny little frame and overwhelmed by scrollwork. The poor angel up top looks like it's bracing for impact, like "Oh no, he's going to burst out of there!" Also I wonder, an engraving of a powerful man. Is this about preserving a likeness, circulating an image? Curator: Undoubtedly both. Engravings allowed for mass production, and hence distribution of his likeness. His portrayal signifies status and power but engraving as a medium was not an easy or particularly fast medium; hence, choosing this method, while relatively inexpensive, indicates a degree of intended formality and permanence. The sharp delineation reinforces concepts of authority. Editor: It’s interesting. As an artist, I’m fascinated by the limitations and the artist’s ability to turn those constraints into aesthetic strength. I mean look how much information is conveyed, solely using line. A kind of optical dance, wouldn't you agree? A true achievement in its way. Curator: Indeed. The artist's skillful manipulation of line transforms mere medium into meaning itself. So, this portrait, at its heart, isn't simply representational. Instead, it exists as a constructed artifact, steeped in symbolic language and conveying social narratives. Editor: When I consider the emotional tone and sheer craftsmanship I feel like something in this fellow's gaze keeps calling to me, from across centuries. It sparks questions in my soul, makes me think about the weight of legacy. Curator: It certainly offers much for meditation, and that is part of the strength in pieces such as these, they serve almost as philosophical touchstones to engage with.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.