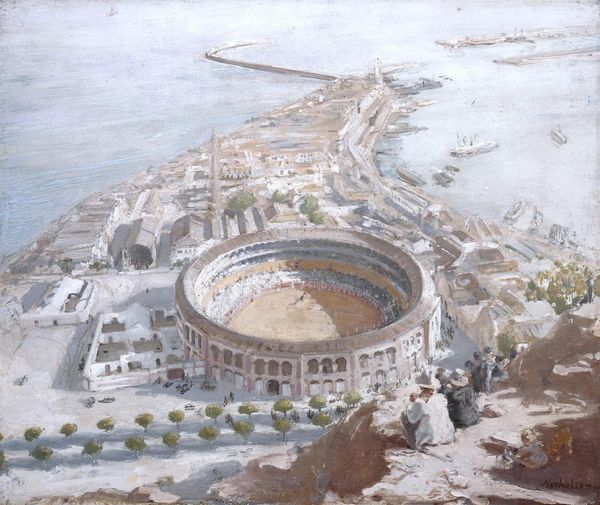

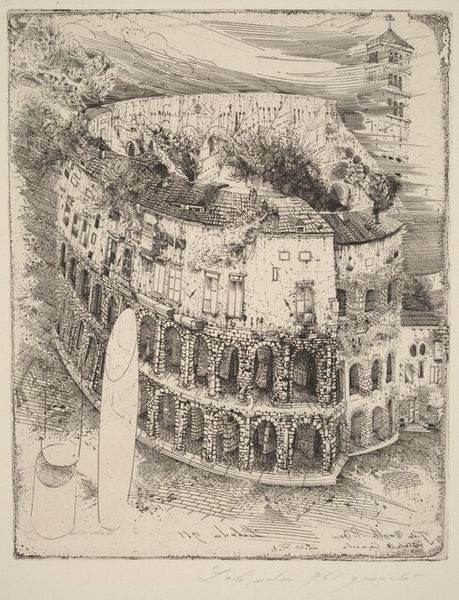

Study for ‘Plaza de Toros, Malaga’ 1935

Dimensions: support: 322 x 411 x 8 mm frame: 484 x 559 x 85 mm

Copyright: © Desmond Banks | CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

Comments

tate 3 months ago

⋮

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/nicholson-study-for-plaza-de-toros-malaga-t07527

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate 3 months ago

⋮

This oil sketch is the second in a series of three works by William Nicholson showing a view from the hills above Malaga, southern Spain. The first work (Tate T05521), a sketchbook drawing, and the final painting (Tate T05520), worked on in Nicholson's London studio at 11 Apple Tree Yard, are also in the Tate's collection. The three pictures derive from a visit made to the distinguished zoologist Sir Peter Chalmers Mitchell (1864-1945) at his house, the Villa Santa Lucia in Malaga, from 7 May to 13 June 1935. This was a working expedition during which Nicholson painted about a dozen small oil studies of landscapes, as well as interiors and still lifes. Together with the few larger paintings made in Britain from on-the-spot studies, these Spanish works were exhibited at the Leicester Galleries in London in June 1936. While Nicholson most often depicted casual, small-scale subjects such as modest still lifes, corners of rooms, or unimposing tracts of landscape, here he chose the most notable view of a famous landmark, the Malaga bull ring. His enthusiasm for bullfighting was deepened by his relationship with the novelist Marguerite Steen (1894-1975), whom he had met as a fellow guest at the villa and who subsequently became his companion for the remaining fifteen years of his life. Steen was a passionate enthusiast for bullfights, to the extent that she rather disapproved of the Malaga bull ring as provincial. Nicholson had already witnessed a bullfight in Segovia on his first trip to Spain in 1933 and was now taken by Steen to the bullfights at the corrida in Cordoba. 'William was a natural aficonado of the bulls,' she recalled in her biography of the artist. 'He knew nothing, or next to nothing of bullfighting, but all that panorama of colour and movement, that mystic relationship between the man and the bull which is the drama of the bullfight, was as if it existed for him alone … He was lost in his own vision (Steen, pp.159-60). While he was given a studio at the villa, Nicholson more often worked around the house and countryside, drawing with pencil and coloured chalks and painting oil sketches directly from nature. He noticed this view of the bull ring on a walk into the town, instantly recording it with an initial drawing in his sketchbook. Steen's friend Caroline (Lena) Ramsden, a fellow guest at the villa, recalled how 'one morning the three of us set off to walk into town, crossing the hill behind the villa on our way. When we came to within sight of the Bull Ring, William took a sketch book out of his pocket and said, "I'm going to paint that". We left him to it, and, on our way back he showed us the drawing which he eventually gave me' (quoted in Nicholson, p.247). Nicholson gave Ramsden the drawing to accompany the finished picture which she had bought before the Leicester Galleries exhibition. This intermediate oil sketch, painted in the evenings towards sunset, was acquired by Ramsden in 1935 or 1936, although whether by gift or purchase is unknown. The viewpoint in both the oil sketch and the final painting is slightly to the left of that in the drawing, so that the peninsula is not so central and the broad diagonal line of the seafront and port sweep more dramatically in line with the bull ring, echoing its curve. Compared to postcard pictures of the bull ring popular at the time, Nicholson tilted the amphitheatre up slightly, giving the viewer a sense of peering down into the pit much as the spectator would have done. This work is not squared up for transfer, and it is unclear exactly how it was enlarged for the finished painting. The final picture is almost exactly twice the size of this sketch and marked with pin holes, suggesting that Nicholson may have used some trick for measuring lengths with a pair of dividers. Unlike his earlier landscapes executed in subdued colours, including the numerous downland scenes at Rottingdean on the Sussex coast where Nicholson lived from 1909 to 1914, and the views of Harlech, North Wales, where he lived towards the end of the First World War, here he employed pale greens, lilacs and peaches to create a delicate effect of glistening light. As Steen later wrote, Nicholson's 'vision of Spain was … pale, pale and glittering: silvered, not gilded, by its heat' (Steen, p.158). The arrangement of the landscape around an elliptical shape, in this case the bull ring, is typical of many of Nicholson's paintings which often centred on a geometrical shape such as an avenue, fountain, cup or bowl. Hilary Lane attributes this to Nicholson's fondness for playing with a mahogany bilboquet (a cup-and-ball) and seeing 'the ball fall satisfactorily into the cup thousands of times' ('Looking Through the Paintings' in William Nicholson, Painter: Landscape and Still Life, exhibition catalogue, Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne 1995, p.33). The Malaga bull ring, known as La Malagueta, opened in 1874 and was to become a lifelong source of inspiration for Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) who was born and spent his youth in Malaga. Yet while in the 1930s Picasso was harnessing the symbol of the bull for radical ends, to suggest sexual potency, the possibilities of metamorphosis, and even national identity in the wake of the Spanish Civil War (1936-9), Nicholson's engagement with the bullfight and its characters was altogether more detached. His sketches and paintings of the Malaga bull ring are consciously distanced from the violence and spectacle of the sport. Viewed from a distance, they convey the architecture and topography, light and shadow of the landscape. Until his death in 1949 Nicholson rejected radical modern styles, continuing to work in the tradition of nineteenth-century realism learnt from Edouard Manet (1832-83) and James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903). As Sir John Rothenstein (1901-92), Director of the Tate Gallery from 1938 to 1964, noted, 'his mind, like his eye, was preoccupied wholly with the intimate segments of the surface of the world that came under his minute and affectionate observation' (Modern English Painters: Sickert to Smith, London 1952, I, p.118). Further Reading: Andrew Nicholson (ed.), William Nicholson, Painter: Paintings, Woodcuts, Writings, Photographs, London 1996, pp.243-9 Marguerite Steen, William Nicholson, London 1943, pp.153-62 Jacky KleinJuly 2002