engraving

#

portrait

#

facial expression drawing

#

medieval

#

old engraving style

#

caricature

#

personal sketchbook

#

portrait reference

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

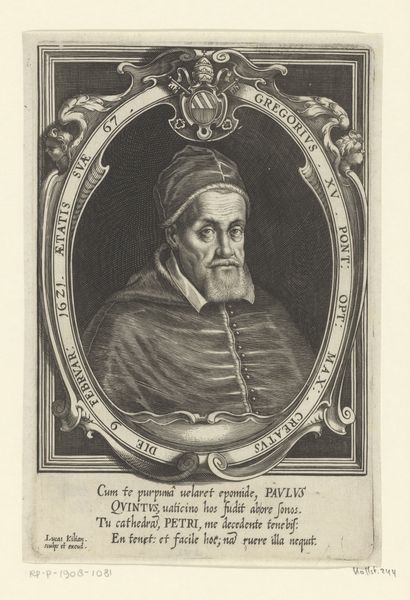

engraving

Dimensions: height 206 mm, width 136 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving, dating from between 1633 and 1676, is titled "Portret van Merovech." Editor: The face… It has an oddly contemporary feel for a historical portrait. There's a caricature-like quality to it, a bluntness that almost seems satirical, but maybe I am swayed by the comical elements that strike me. Curator: The artist, Jean Frosne, situates Merovech III, King of the Franks, within a visual language that draws heavily from both historical record and the socio-political concerns of his time. The prominent display of heraldry and Latin script establishes authority, grounding the image in a verifiable lineage, or rather constructing the legitimization of royal lineage, a crucial project throughout early modern Europe. The very act of creating and circulating portraits of rulers—real or legendary—reinforced a certain image of power, and it helped define what it meant to be a ruler, no? Editor: Exactly! The iconography screams "royal power"–the crown with its fleur-de-lis motifs, the heavy chain suggesting wealth and status. But what interests me is the almost cartoonish rendering of Merovech’s face, or specifically his nose. Is this poking fun at power, challenging its very foundation by introducing such a subtly humanising—almost mocking—element? Perhaps playing with established symbols to deliver a contradictory message. Or do these 'imperfections' humanize the historical figure in question? What kind of cultural memory is Frosne trying to construct here? Curator: These visual tropes certainly have emotional and cultural weight that has varied greatly depending on context and historical era. Let’s consider this in terms of contemporary notions of caricature and its relationship to power, but, moreover, let us contextualize it within seventeenth-century notions of kingship and representation to understand the significance of Frosne’s artistic decisions. I wonder, also, what theoretical tools we can use to investigate the contemporary appeal of his representation. Editor: True. This is not merely an issue of representation, but how symbols acquire layered meanings and emotional valences. Ultimately it’s about our enduring engagement with, and our interpretations of, these signs. Curator: Indeed. Seeing it from a broader perspective of visual history, the symbols act like historical anchors connecting past and present cultural understandings of power, presentation, and persona. Editor: I see how approaching it this way helps one appreciate this print's intricate conversation across time. It’s definitely more than just a king's portrait; it’s a symbolic language waiting to be decoded.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.