drawing, print, paper, ink, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

pen sketch

#

old engraving style

#

paper

#

ink

#

pen-ink sketch

#

genre-painting

#

academic-art

#

nude

#

engraving

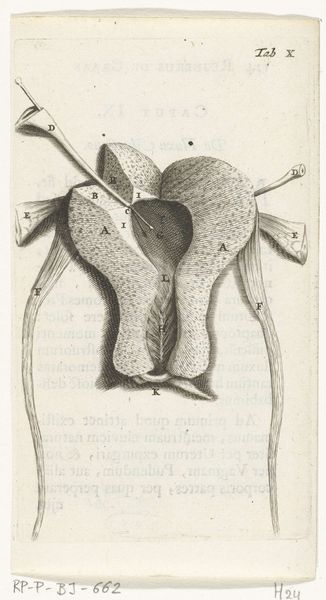

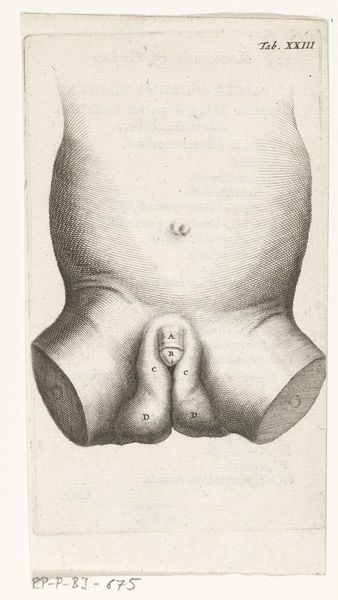

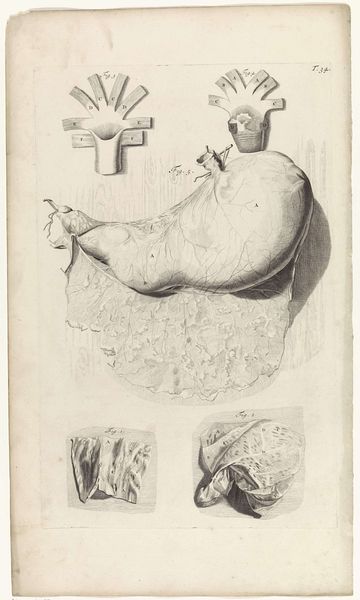

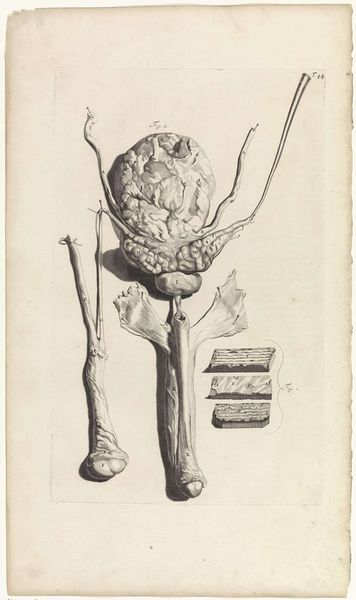

Dimensions: height 140 mm, width 80 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

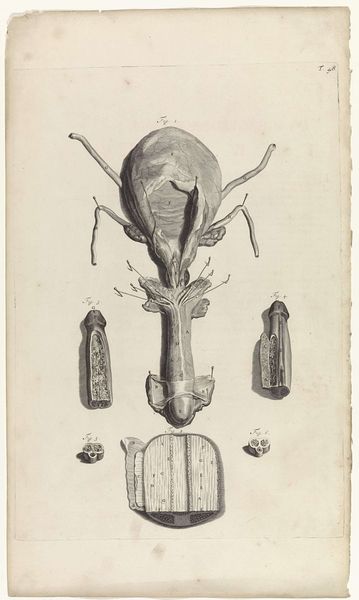

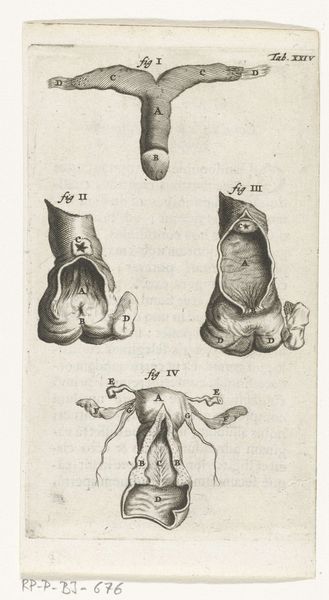

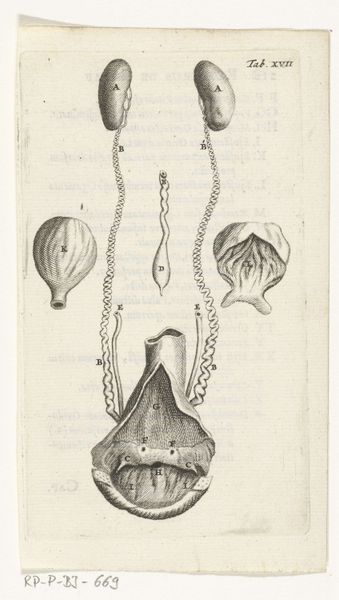

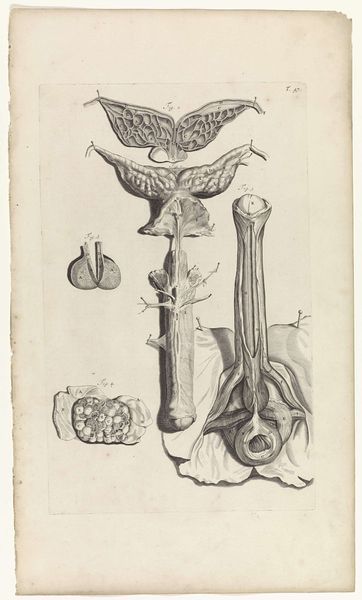

Artist: Wow, that's… intense. Almost alien, in a strange, detached way. Is it supposed to be beautiful? Historian: Well, that’s a layered question! This engraving, "Prints of the Female Reproductive Organs," was made in 1672 by Hendrik Bary. It's ink on paper and currently resides in the Rijksmuseum collection. Bary was quite known for his precise and detailed anatomical drawings, and this print fits that mold. Artist: Precise is right! It feels almost clinical, like peering through a microscope, though, without the color, of course. It is quite mesmerizing because of its exactitude. Historian: Exactly! These weren’t necessarily intended as artworks in the way we might understand them today. Instead, prints such as these served the rising needs of medical and scientific education, documenting the body with detail made available to the masses via printing technology. Artist: So, art serving science? Historian: Absolutely, but think too about the power structures at play. Access to knowledge was being democratized via printed image, even as women were barred from engaging in that very anatomical and medical field. Artist: So, a glimpse into the female body, visualized and disseminated largely by men... I feel a pang of unease. Is that projection or intentional, or even both? Historian: Perhaps both! On the one hand, such detailed anatomical prints fueled a growing understanding of the human body, even normalizing looking inside. However, what does it mean to dissect the female anatomy and expose it, however clinically, for widespread public viewing? Consider too who benefits from seeing such images and what cultural and institutional biases frame such access. Artist: Looking at it this way, I understand more what I’m looking at beyond the surface of what I see... It’s really quite a striking contrast. The delicate detail feels almost violated by the bold scientific ambition. Historian: Precisely. These prints can open avenues for reflection. What does it mean to gaze directly at what's generally kept hidden, and whose perspectives and narratives gain or lose from it?

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

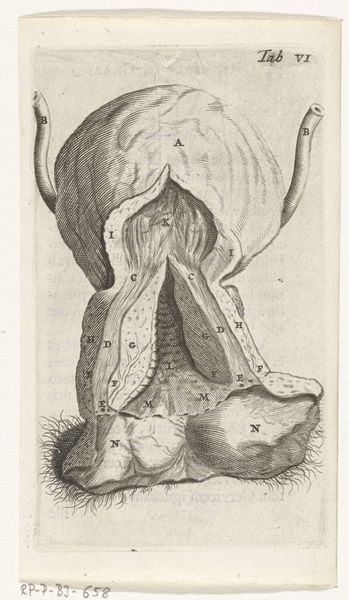

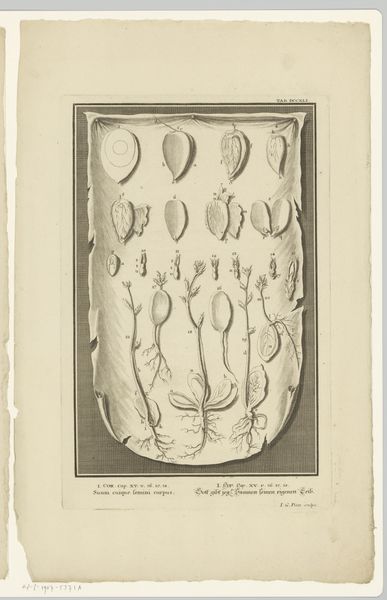

In 1672, physician and anatomist Reinier de Graaf published his De mulierum organis about the female reproductive organs. The book contains detailed prints by Hendrik Bary, among them several of the vagina. De Graaf was the first to conclude that a foetus was the product not just of a man’s seed, but also of a woman’s egg. He discovered what he called blisters, which later became known as Graafian follicles.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.