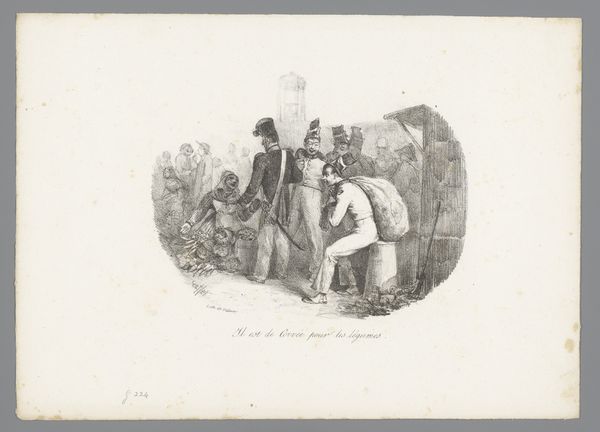

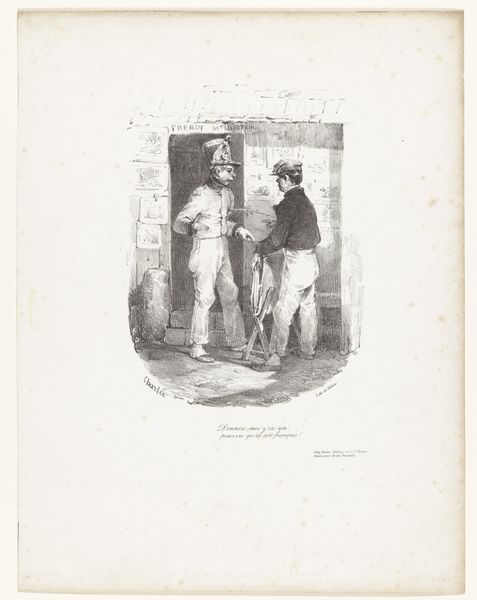

drawing, pencil, graphite

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

graphite

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 213 mm, width 299 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

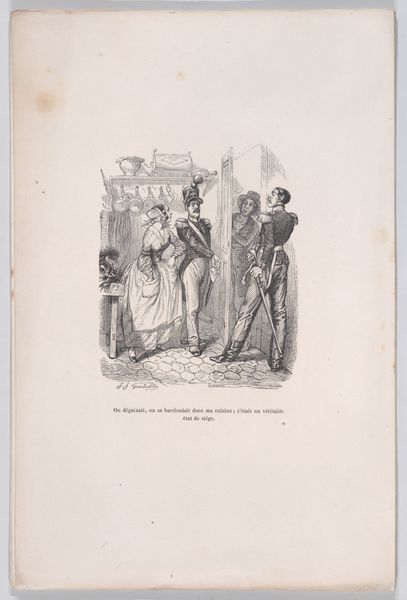

Curator: This drawing, attributed to Auguste Raffet and dating from the 1820s, is titled "Jean-Jean met een emmer water om schoon te maken," or "Jean-Jean with a bucket of water to clean up." It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. What's your initial impression? Editor: Well, there’s a slightly unsettling atmosphere here. While the scene depicts what looks like everyday cleaning duties, the expressions are oddly stiff, almost caricatured, creating a sense of societal critique rather than simple genre painting. Curator: Precisely. I think that's what lends it the staying power of romanticism even in a common theme of everyday workers, drawn using pencil and graphite. The repetition of figures, their uniforms, perhaps speaks to forced labor or service. The water bucket is just the surface. Editor: Indeed. The bucket itself is placed strategically at the periphery of our central figures. This highlights the societal message over a story or personality-centered experience. This aligns well with my historical research of this era, as public order and its visual display became increasingly centralized concerns. How were workers perceived and depicted? This drawing contributes to that evolving visual culture. Curator: The "Jean-Jean" in the title then takes on another layer of meaning—could this refer to a generalized worker figure rather than an individual? If so, does that affect its significance beyond a simple genre scene? Editor: Absolutely, it pushes the drawing into the realm of social commentary. It encourages the viewer to ask why Raffet chose to depict this particular scene and to consider what social forces might be at play. Also, it would be useful to research Raffet's circle—did he share similar political and social perspectives? Curator: It raises the question: Is he sympathetic to this “Jean-Jean” character? Or is it an observational piece void of sentimental empathy? These romantic undertones and this approach would explain the ambiguity of his position through powerful imagery. The figures, their poses—it’s all very deliberate. Editor: So, this modest drawing actually holds a mirror up to societal perceptions and the politics surrounding labor in the early 19th century. Curator: Precisely. This allows us to see the visual representations and hidden social narratives of the working class—their service, suffering, and the societal structure. Editor: A fantastic intersection of art and social history, demonstrating how everyday images can unveil complex truths about our past.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.