Dimensions: 244 × 183 mm (image); 272 × 195 mm (primary support); 431 × 296 mm (secondary support)

Copyright: Public Domain

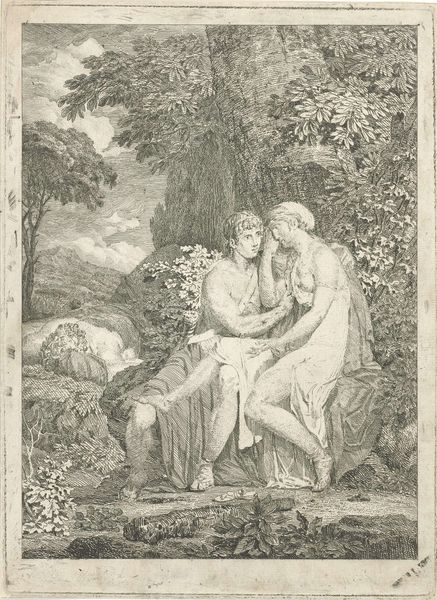

Curator: This lithograph, "Plate One from Misery," by Charles Rambert, created in 1851, pulls you in, doesn't it? It’s currently held at the Art Institute of Chicago. What strikes you immediately? Editor: Well, initially it’s the stark contrast – you've got this almost idyllic couple, draped in classical-style clothing, then, lurking in the background, a figure embodying misery. The rendering style, with all those etched lines, speaks volumes about the printmaking process of the time. Curator: Yes, and notice how the light falls, almost like a stage lighting. There's a very theatrical Romanticism in the poses and the implied narrative. What do you think about how this interplay sheds light on material conditions of nineteenth-century France? Editor: Well, lithography made art more accessible. These prints were commodities. I see Rambert, as someone embedded in the economy of art production. And here, we are presented with a social commentary, a story intended for mass consumption—literally a print made for circulation, reflecting societal woes while being part of it, really. Curator: True, there is such complexity. He uses classical allusions, a sort of reaching towards the ideal with these almost allegorical figures, yet names the print "Misery," in all its quotidian darkness. It is deeply spiritual and raw, simultaneously. Editor: The medium itself becomes part of the message, it gives access to people otherwise barred from the luxury world of art, no? We are really compelled to wonder about this supposed democratization versus how art production exploits artistic labor. Curator: And look at the posture. The misery figure is low, squatting, and small. The idealised couple, although clothed in classical drapery, are similarly bound: their expressions pained, his raised hand almost a plea or question, not celebration, while the woman beside him, collapses under the emotional pain of the Misery figure squatting in the background. Is there escape, even in beauty? Editor: This really underscores art’s complex position: capable of criticizing social injustice while also perpetuating certain production methods. This image itself circulated; becoming a document deeply tied to the material and social fabric. Curator: Seeing the light and shadows as commentary, rather than just technique, that’s so potent here. It echoes in you as viewer! Editor: Absolutely, making us, the consumer, very active participant of its play.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.