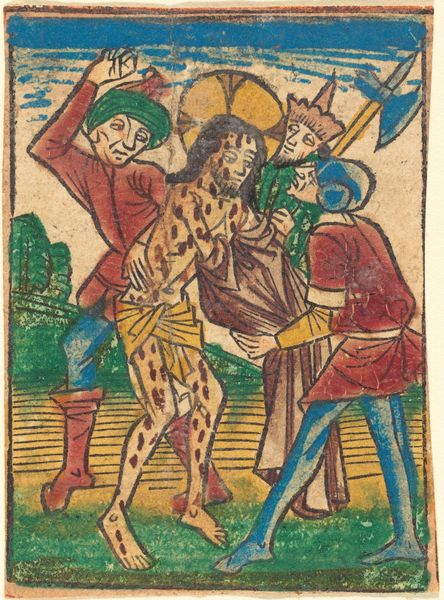

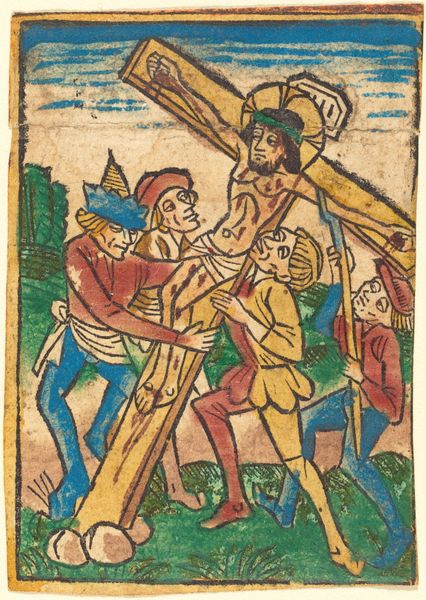

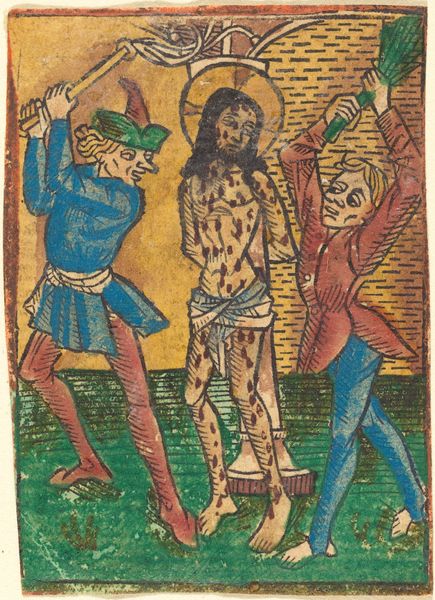

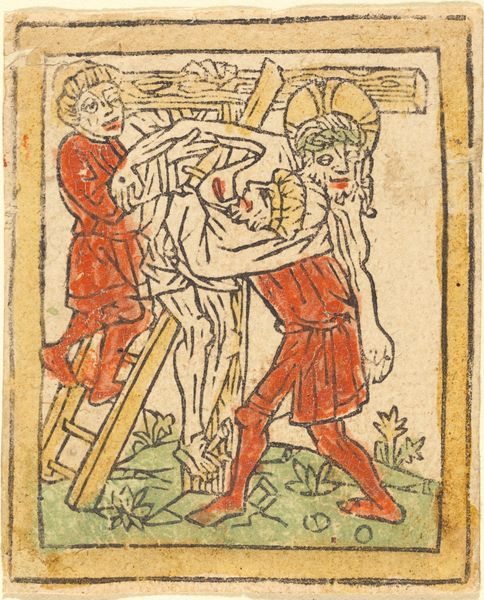

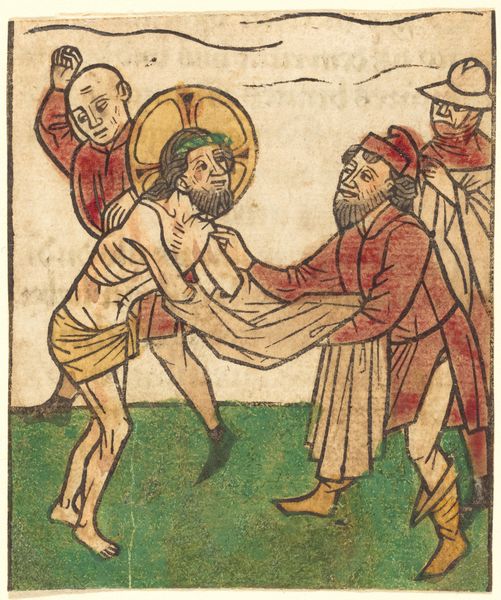

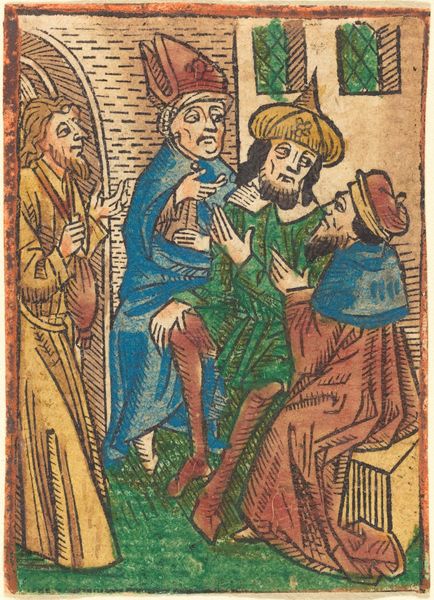

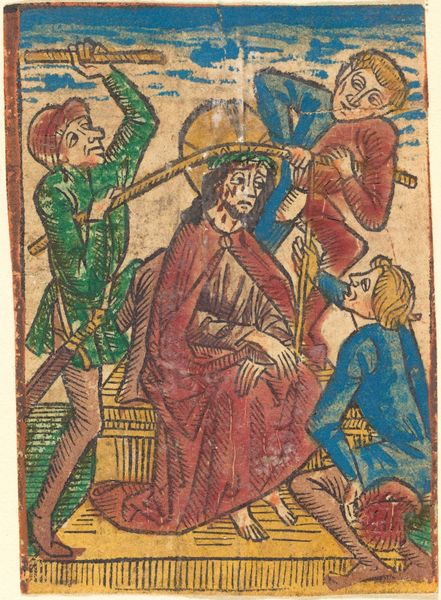

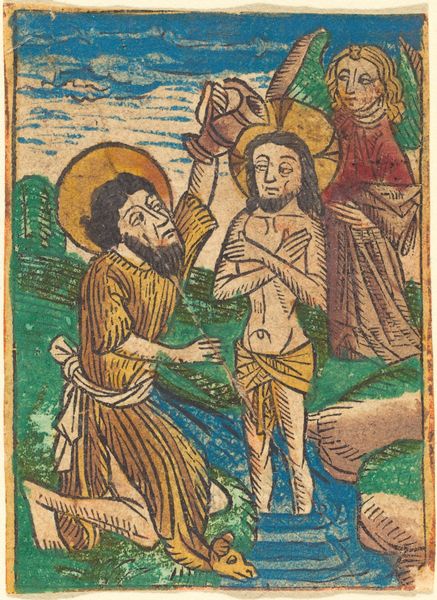

print, woodcut

#

medieval

#

narrative-art

# print

#

figuration

#

woodcut

#

naive art

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

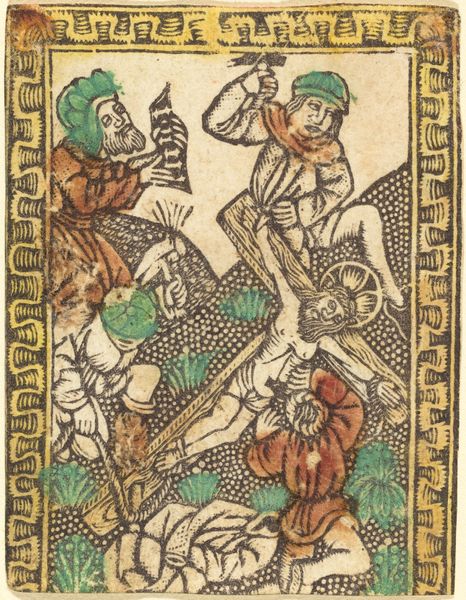

Curator: Looking at this piece, what immediately strikes you? Editor: It has an intensity born from stark color and line, hasn't it? A raw visual immediacy despite the obviously grave subject matter. Curator: That rawness aligns well with the medium. This is a woodcut, likely from around 1490, titled "Christ Nailed to the Cross," attributed to an anonymous artist of the Northern Renaissance. Woodcut prints, especially during this period, involved significant labor. Can you imagine the skill required to carve these details in relief on a block of wood? Editor: Absolutely. And we need to also consider who this labor actually benefitted, and who could access this image. This wasn't meant for some private collection, was it? Printmaking allowed wider dissemination of religious narratives to people, even illiterate ones, and often functioned as a crucial form of cultural and political education for marginalized populations. Curator: Indeed. The prints served as accessible conduits of the Church's messages and could even be tied into devotional practices. But even then, consider the price of pigment! The colored inks, though simple, reflect resources and skill investments to capture viewers' eyes. It raises questions about production value, as well as how these prints functioned commercially in a developing marketplace. Editor: Precisely. It also invites a complex, intersectional discussion. Notice the figures, the emotional states implied by their gestures. Consider how a peasant woman would experience such an image of torture, likely experiencing extreme violence and limited agency in her own life. How might that affect their interpretation of divine suffering versus that of, say, a merchant with ties to the very trade practices enriching some while impoverishing others? Curator: The contrast between Christ's passivity and the active violence inflicted upon him is compelling, isn't it? Thinking materially, I wonder if the specific tools used and the quality of paper affected the final impression intended. The linear nature of the woodcut aesthetic lends itself well to rendering pain and suffering—those dark lines cut so starkly into the image create drama on a technical level. Editor: Agreed. It's powerful because of its simplicity, the unvarnished portrayal. Even within this seemingly simple aesthetic, consider the layered complexity embedded in representing power, oppression, and resistance to violence in the artwork. I appreciate seeing this anonymous artwork today and having access to these important narratives, especially the way the use of print enabled the sharing of cultural history and visual narratives. Curator: Indeed, analyzing not just *what* the print depicts but also the materiality behind the *how* and *why* adds depth to our comprehension of this image, which also shapes an era's social narratives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.